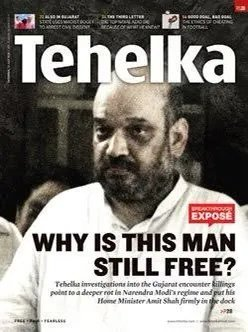

In 2010, Amit Shah, then Gujarat’s minister of state for home, was arrested and jailed on charges that he had ordered the state police to kill an alleged gangster named Sohrabuddin Sheikh, his wife Kausarbi and his associate Tulsiram Prajapati.

Shah was arrested by the Central Bureau of Investigation after the Supreme Court transferred the case from the Gujarat Police to the central agency to ensure an impartial inquiry.

But it was the Gujarat Police that first raised suspicions about the alleged involvement of police officials in the killings, in a report that it submitted to the Supreme Court.

The report had been submitted on the orders of Kuldip Sharma, a decorated Indian Police Service officer who had won the President’s Police Medal in 2001, and who was an additional director general of police in the state at the time.

Shah was released on bail a few months after his arrest. Two years later, a three-decade-old case against Sharma came back to life. In 2012, Narendra Modi, the chief minister of Gujarat, gave official sanction to prosecute Sharma in a case dating back to 1984, in which he had been accused of voluntarily causing hurt to and wrongfully confining an alleged smuggler in a police station in Bhuj district.

In February this year, a court in Gujarat convicted Sharma and a former sub-inspector named GH Vasavada of wrongful confinement and sentenced both to three months’ imprisonment. An arrest warrant for both was issued on October 10.

While Shah, now India’s home minister, was acquitted in the Sohrabuddin case in 2014, Sharma, 70 and living a retired life in Ahmedabad, faces imminent arrest in the 1984 case.

In October, Sharma filed an appeal in the Supreme Court, which is yet to be heard.

The case

The case against Sharma dates back more than 40 years, to his tenure as deputy superintendent of police, Kutch.

During this time, he was accused of assaulting an individual named Haji Abdul, now deceased, also known as Ibhalaseth Haji Ibrahim Mandhra, inside a police station. According to records that Sharma later submitted in court, Mandhra was a habitual offender and was involved in several criminal cases over his lifetime, including a gold seizure case in 1982.

The case is based on a complaint filed not by Mandhra, but by Shankarlal Govindji Joshi, who identified himself as a political worker. He claimed that on May 6 that year, he along with Mandhra, went to meet Sharma to complain about alleged police harassment of some individuals involved in another case.

Joshi alleged that during this visit, Sharma assaulted and “illegally detained” Mandhra for about an hour. On May 8, 1984, Joshi filed a complaint against Sharma and his officers under several sections of the Indian Penal Code.

In 1987, Sharma filed an application before the additional judicial magistrate, Bhuj, who was hearing the case, asking for it to be quashed. He argued that the requisite sanction from the government had not been obtained, under Section 197 Code of Criminal Procedure, a provision that mandates prior approval from the relevant government authority to prosecute public servants for acts performed in the course of their official duties.

The magistrate rejected his appeal, but in a subsequent appeal, the Gujarat High Court issued a stay on the case in 1995.

However, in 2012, the Gujarat government granted sanction to prosecute Sharma, reviving the case.

Sharma approached the Gujarat High Court, challenging the validity of the sanction – but the court dismissed his petition in 2015. Subsequently, he moved a special leave petition in the Supreme Court.

On May 15, 2015, senior advocate Kapil Sibal appeared for Sharma in the Supreme Court. He argued that the Gujarat government and the then chief minister tried “every trick in the book to send the officer behind the bars. It is very well known why such action was taken against him and the state government was hell-bent to wreck vengeance with Sharma.”

The Supreme Court did not quash the case, but stayed the proceedings in lower courts while the petition was pending in it.

After nine years, in November 2024, the Supreme Court dismissed Sharma’s petition, and directed the trial court to conclude the case within three months. In this hearing, Joshi was represented by senior advocate Mahesh Jethmalani, also a member of the Bharatiya Janata Party and a nominated member of the Rajya Sabha since 2021.

In February this year, additional chief judicial magistrate, Bhuj-Kutch, Babubhai Madhavlal Praj, found Sharma and Vasavada guilty – it sentenced both to three months’ imprisonment and fined them Rs 1,000. If they defaulted on this payment, they were to be jailed an additional 15 days.

The two filed a plea in the Gujarat High Court, challenging the judgement and seeking exemption from surrender.

Among their arguments was that the sessions court’s verdict was invalid since it also recorded convictions under sections Section 409, read with 120(b), which had not thus far been invoked in the history of the case.

In response, the state contended that inclusion of these sections was merely a “bona fide and typographical” mistake, which could easily be corrected through an application before the trial court.

On October 13, the high court rejected Sharma and Vasavada’s plea.

Political vendetta?

Over the years, Sharma has argued in courts that the case against him is flawed and politically motivated.

For instance, he argued before the additional chief judicial magistrate in Bhuj that before the government sanctioned his prosecution in 2012, it had appointed a public prosecutor to defend him and Vasavada.

The court noted that Sharma argued that it was a contradiction that “on one hand, the government says that the accused are innocent, while on the other hand, sanction has been given against the accused”.

In October, when Sharma and Vasavada moved the high court, challenging the sessions court’s verdict, the state government itself opposed their plea.

In his special leave petition before the Supreme Court in 2015, Sharma alleged that he had been a victim of “malafide” intentions on the part of Narendra Modi and Amit Shah.

Apart from the Sohrabuddin case, the petition listed other instances in which Sharma’s actions had allegedly irked the chief minister and minister of state for home.

Sharma noted that in 2010, he had recommended further investigation into allegations that Shah had received Rs 2.5 crore in “the matter of a case about a fraud in Madhavpura Mercantile Co-operative Bank Limited, Ahmedabad”.

Ketan Parekh, who was convicted of insider trading in 2008, was an accused in that case. The petition claimed that the state’s criminal investigation department had traced several calls between Parikh, Shah and an intermediary.

Another instance listed in the petition pertained to a case against the dancer Mallika Sarabhai “and the allegation was that she was using her organization to take people illegally to USA”. It recounted that Sarabhai had moved the Supreme Court “against the Chief Minister and others with regard to communal riots in Gujarat during 2002”.

An investigation by the criminal investigation department into the allegations against Sarabhai “revealed that no offence was made out”, the petition stated. Despite this, Shah “was bringing pressure to arrest and charge-sheet Ms. Sarabhai”.

Sharma ordered the case closed, which irked Shah and Modi, who, the petition claimed, “expressed his displeasure about it later on when the Petitioner had an occasion to meet him in person”.

A third instance involved allegations of extortion against Kamlesh Tripathi, a “close associate and political ally” of Amit Shah. Sharma had directed the superintendent of police to register the offence despite “pressure” and “veiled threats” from Shah, the petition alleged.

It added, “Immense pressure was brought on the concerned SP, Shri Anil Pratham not to do so. Shri Amit Shah even conveyed a veiled threat to the SP. Eventually the complaint came to be registered much against the wishes of Shri Amit Shah.”

Yet another incident involved a police officer named Rajkumar Pandian, who, internal investigations had found, had made “wild and false allegations” against a superior. Accordingly, Sharma had recommended “major penalty” against Pandian, but “no action was taken against Shri Pandian by the State Government”.

The petition noted that Pandian “was subsequently arrested by the CBI and was a co-accused with Amit Shah in the murder of Soharabuddin and Kauserbi”.

Other instances

Sharma is not the only police officer in Gujarat to allege that he is a victim of a political vendetta.

In 2015, former police officer Sanjiv Bhatt was dismissed from service after the Centre accepted Gujarat’s recommendation for his removal on 11 charges. In 2019, he was sentenced to life imprisonment in connection with a 1990 custodial death case. He remains jailed.

In 2011, he had filed an affidavit in the Supreme Court, alleging that Modi and senior officials of the Gujarat government were responsible for the 2002 violence, an accusation he repeated before the Nanavati Commission.

His lawyer had argued in court that Bhatt’s arrest was “politically motivated”.

Similarly, Gujarat’s former director general of police RB Sreekumar was arrested in 2022 over alleged forgery and conspiracy. He had testified against the state in the 2002 riots case. He claimed that his arrest was malicious.

Also in 2022, Satish Chandra Verma, a police officer who was involved in the Ishrat Jahan fake encounter investigation, was dismissed a month before retirement. Verma was part of the special investigation team formed by the Gujarat High Court, which in 2011 found that a woman named Ishrat Jahan and three others were killed in a fake encounter in 2004, when Amit Shah was the state’s minister of state for home.

In 2014, when he filed a petition against a transfer to the North East, he alleged that the move was motivated by his investigation into the Ishrat Jahan case.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting