In August, pulmonologist Avya Bansal received a 65-year-old patient in Mumbai. She came intubated, in a state of respiratory distress.

Bansal immediately carried out a quick screening test for various pathogens, and found it to be positive for the acinetobacter bacteria.

Acinetobacter is found in abundance in hospital environments – and the bacteria is always on the lookout for immuno-compromised people.

The 65-year-old had undergone a hip replacement surgery at another city hospital. Five days later, she developed fever, then pneumonia and slipped into respiratory distress. When she came to Bansal in Bombay Hospital, she was on a ventilator.

“A classic case of hospital-acquired infection,” Bansal noted.

The senior citizen already had lung fibrosis. Acinetobacter worsened it to the extent that her lungs could no longer take in or expel air even as antibiotics dripped in vain through a saline bottle.

A week later, she died of respiratory failure.

Bansal said infections, like hers, could “possibly be prevented” if the hospital staff followed stringent infection control measures for immuno-compromised patients.

But the patient’s family did not know of such a concept. Even if they did, there was no way to check the infection rate at the hospital where she had been admitted for the surgery. Such data is not publicly disclosed by hospitals in India.

Scroll contacted the country’s top public and private hospitals, seeking data on their infection rates. While some public hospitals shared the data in response to a Right to Information request, barring Wockhardt hospital, all leading private hospital chains such as Fortis, Medanta, Max and Apollo, ignored or declined our requests.

In this report – the second part of our series on healthcare-associated infections in India – we examine the importance of hospital-level data on infections, and the consequence of hospitals failing to make such disclosures.

A black box

Around the world, many countries have made it mandatory for hospitals to publicly declare their infection rate.

In the United States of America, for instance, an online repository called Hospital Compare not only provides details of beds, occupancy and specialities available at the hospital but also its infection rate.

The Australian government runs a portal where patients can check hand hygiene compliance by hospitals. In the United Kingdom, the government collects infection rate data from each hospital and summarises it in their annual reports.

Why is the disclosure of infection rate by hospitals important?

Dr Vijaya Patil, the head of the infection control committee at Tata Memorial Hospital, the country’s largest cancer institute, explained: “If I have to decide where to get operated, I can make an informed decision if I know a hospital has high compliance with hand hygiene and low HAI rate. But if that hospital has a high incidence of hospital-acquired infections, no matter how good the surgeon is, I still stand a chance of getting infected after the surgery.”

And yet, India’s top hospitals – both public and private – do not make such public disclosures.

Even the 90 hospitals that are part of India’s only monitoring system, HAI Surveillance network, are not required to regularly report their infection rate data to the network.

Scroll filed a Right to Information request with the Indian Council of Medical Research, asking for data on the infection rates at each of these 90 hospitals, of which 69 are government-run. In its response, the ICMR said “patient-level data are not collected” and “rates for individual hospitals were not reported” to them.

The network does not carry out regular infection surveillance at these hospitals. “HAI surveillance is conducted on an event basis, and only overall HAI rates are calculated,” ICMR said, which means that ICMR may ask hospitals to submit their infection rate – periodically, say once in a year or two years – for academic and research purposes.

The only regular monitoring of infection control protocol at hospitals by a third party is done by the National Accreditation Board for Hospitals and Healthcare Providers – a body that sets standards and provides accreditation to healthcare organisations. It conducts regular inspections at over 2,700 hospitals that it has accredited.

But that implies that most of the 70,000-odd hospitals in the country are not monitored at all.

When Scroll sought data on the infection rates at these 2,700 hospitals, NABH declined the request. “We cannot share this data. It would be a breach of confidence,” said Dr Atul Mohan Kochhar, the chief executive officer of NABH.

A Right to Information request was filed with the Quality Council of India, which heads NABH, asking for data on hospitals whose accreditation was cancelled due to poor infection control. The QCI replied that the “data asked in desired format is not available”.

Kochhar explained that NABH would have to ask each of the 2,700 hospitals for permission to share their data. “If the government made the notification [of infection rates] mandatory, just like it had for Covid-19 infections, then hospitals will have to comply,” he said.

State of India’s AIIMS

Even in India’s best government hospitals, infection control practices hardly inspire confidence.

In August, Scroll filed a Right to Information query with all the 20 functional All India Institutes for Medical Science – the top-most public hospitals that come under the Union health ministry.

Only 14 AIIMS provided either partial or complete healthcare-associated infection rates.

Strikingly, the oldest AIIMS in the country, AIIMS Delhi, stated they “did not have the required information”, despite being at the helm of the HAI Surveillance Network. Scroll filed a first appeal, but the hospital did not change its stance.

Eight of the AIIMS reported 1,711 cases of healthcare-associated infections between January 1, 2024, and July 31, 2025.

A hospital ought to record at least four kinds of common infections: bloodstream infection, caused by catheters or tubes that carry medicines and fluids to the body, ventilator-associated pneumonia, an infection in lungs due to prolonged ventilator use, urinary tract infections caused due to germs in the catheter, and surgical site infection, which occurs when the place of incision gets infected.

But of the 14 who responded to the RTI, at least nine AIIMS failed to record all four types of infections.

An analysis of RTI responses by all the institutes paints a worrying picture. Not only do infection rates differ vastly among AIIMS, some are alarmingly far from meeting international benchmarks.

Scroll also sought minutes of the meetings of the infection control committees at AIIMS. Only four institutes shared their minutes.

In three AIIMS, the infection control committee met only once or twice a year. In AIIMS Gorakhpur, the infection control committee has not met even once to discuss their infection protocol and correct their lapses. In AIIMS Bilaspur, the last meeting of the infection control committee happened in February 2024. No meeting was conducted this year till July 31. Without such meetings every month, hospitals are not able to identify and correct lapses in infection protocol in time.

Since AIIMS Delhi did not provide the information under RTI, we checked their annual reports of 2023-24. It reported that out of 3,811 environmental samples – swabs taken from walls, tabletops and surfaces of equipment, air, bedrails, water– 26% were found unsterile. That indicates a high infection risk to patients.

Similar concerns arose in other institutes. In AIIMS Rishikesh, in multiple audits of patients who got hospital-acquired infections, the committee noted that hospital staff had not followed hand hygiene protocols due to inadequate supply of hand rub.

For instance, the hospital noted that a burns patient had possibly been infected in May because of “inadequate supply of hand rub”, “routine environmental cleaning not done due to no supply” , and “scrub the hub not done properly”. Scrub the hub is a critical healthcare procedure to prevent infection from catheters. The catheter’s connection point is scrubbed with an antiseptic to kill microbes.

Private hospitals

We also contacted 10 of the most prominent private hospitals and hospital chains in India – Fortis, Apollo, Medanta, Aster Medcity, Wockhardt, HN Reliance, Kokilaben Dhirubhai Ambani, Nanavati, Artemis, and Max Superspecialty – asking them to share their latest HAI rates, the number of patients who caught HAI, the number of associated deaths, and their infection control protocol.

Fortis, Apollo, HN Reliance and Kokilaben Dhirubhai Ambani hospital declined to share their data. Medanta and Aster Medcity did not respond to our request. Artemis, Nanavati and Max Superspecialty hospital acknowledged our request but did not provide data.

Only Wockhardt hospital responded. Dr Parag Rindani, chief executive officer of the group, told Scroll that the hospital chain’s overall healthcare associated infection rate for 2024 stood at 0.6. That is well within CDC standards.

Rindani said the hospital’s infection committees meet every month. They follow what NABH mandates: focus on high-risk areas, hand hygiene, and surgical protocols.

“And yet healthcare-associated infections are part and parcel of treatment in a hospital,” Rindani said. “There is always an inherent risk of infection.”

None of the hospitals, including Wockhardt, display their infection rates on websites for patients to check. “If there is a standardised method of reporting, then it can be done,” Rindani said, explaining that each hospital has its own system of monitoring.

Patil, head of Tata hospital’s infection committee, said that if hospitals start displaying their infection rates, compliance will pick up. “If hospitals know they are being watched, they will make efforts. Otherwise they will cut corners in infection control.”

Kochhar, NABH’s CEO, agreed. “We do need central data to capture these key indicators and make it public. Big corporate chains do maintain all internal records, but they don’t find it necessary to publish it.”

While India’s corporate hospitals might be unwilling to disclose data on infection rates, officials at these hospitals emphasised that they have invested heavily in infection control.

At PD Hinduja Hospital in Mumbai, infection control officer Dr Shaoli Basu briskly walks through all wards every day, with a UV marker in her hand that she randomly rubs on tables, hospital surfaces and bed rails. She returns 24 hours later to the same spots, this time with a torch. If the invisible mark glows in its flash, Basu pulls up the housekeeping staff for not cleaning properly.

Basu introduced a series of measures, including the UV marker, as part of the super specialty hospital’s infection control protocol.

The results are evident: when Scroll visited the hospital in June, its records showed the rate of blood stream infection that can spread through central line insertion were within the benchmarks set by US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In contrast, a retrospective study at AIIMS in Bhopal of its intensive care unit patients between 2015 and 2019 found blood stream infection rate at 33%. “We found that several infection control protocols were missing in the hospital,” said author Dr Sentenna Chenchula, who worked in the hospital’s microbiology department till 2021.

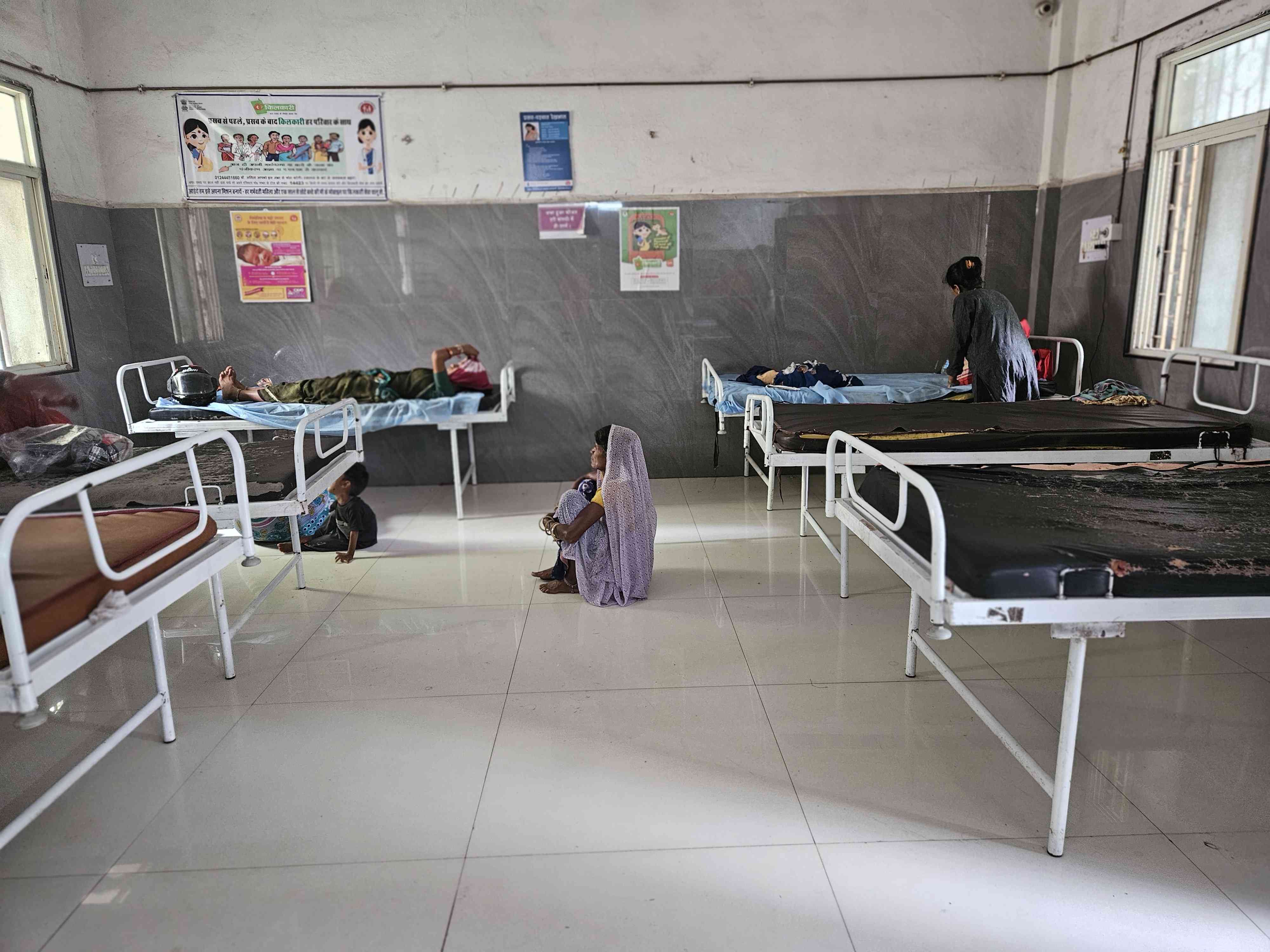

A rural hospital in MP

The vast majority of public hospitals in India – the first point of care for many Indians – fail to prioritise infection control because of scarcity of human and financial resources.

In Madhya Pradesh’s industrial town of Pithampur, for instance, the 30-bedded government hospital is the only treatment centre for a large migratory population that has settled from nearby districts to work in the factories of the country’s largest automobile manufacturers.

Every day, 300 people visit the outpatient department and 10 get admitted.

A visit to the hospital in August showed that there were no hand sanitisers or even a wash basin in the two hospital wards.

Hand hygiene – washing hands or using alcohol based rubs – is a first line of defence against pathogens. According to the World Health Organisation, there are five key moments when hospital staff should sterilise their hands: before touching a patient, after touching a patient, before any aseptic procedure, after touching a patient’s surroundings, and after exposure to any body fluids.

Staff nurse Mamta Jamra said there were too many patients and very few nurses for her to follow hand hygiene. “The wash basin is outside the ward,” she said. “And it is not possible to go out to wash hands after we see each patient.”

Dr Ajay Girwal, in-charge of the hospital, admitted that sepsis cases were common. “But even if I suspect the source of infection to be in the hospital environment, we don’t send samples for testing,” he said. That’s because neither do government guidelines mandate such testing nor are diagnostic facilities easily accessible, he explained.

The nearest laboratory in Indore is 35 km away but it is overburdened.

Nurse Sulochna Pal said they regularly clean the operation theatre but the samples to test for microbial growth are sent every quarter when deep cleaning and fumigation is undertaken. “If we send six to seven samples, they test only three,” Pal said.

Pal said they have received no training on infection control practices. “We learnt how to collect samples from the operation theatre on YouTube,” she said.

Undetected pathogens

The divide is not just between public and private hospitals. Within private hospitals too, the bulk fail in basic infection control practices.

Many patients discover this the hard way.

Freelance writer Deepali Rathod’s father underwent a cataract procedure at a private hospital in March. Within 10 days, 68-year-old Rajendra Gupta, who runs a transport business, had lost all vision in his left eye. He has only 30% vision in the right eye.

When Gupta got fluids from his eye tested, they were found to be infected by pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteria, a highly resistant bug that is often found growing on unsterile surgical instruments.

Rathod and her husband Deep, an IT professional, then began to trace patients treated by the hospital where the surgery had taken place – Dr Pandit Eye Surgery and Laser Hospital in Navi Mumbai.

“I found six patients who lost their vision after undergoing a procedure at the hospital between 2013 and 2025. All because the doctor did not undertake proper sterilisation,” she said. It had gone undetected also because the hospital was not mandated to disclose infection rates.

Rathod, a former journalist, then approached the local police in Vashi to register a first information report. When they refused, she contacted the police commissioner and Maharashtra health minister who directed the district civil surgeon to conduct an inquiry.

Thane civil surgeon Dr Kailash Pawar told Scroll that their inquiry found negligent practices by the hospital. “We wrote a letter to the Navi Mumbai municipal corporation to conduct an inquiry into the hospital’s infection control practices and another letter to the police to take action,” Pawar said. Eventually, the accounts of six other patients were added to the FIR.

Six months after Gupta’s surgery, the hospital was sealed in August. In September, following multiple media reports, the Navi Mumbai Municipal Corporation also suspended Dr Chandan Pandit, the surgeon who operated on Gupta.

When contacted by Scroll, Pandit, whose father owns the hospital, said he could not comment since the matter was sub-judice.

Rathod’s persistence forced the authorities to act. But she worries that may not be enough. “The doctor still has a licence to practice,” she said. “We filed a complaint with the state medical council. It has so far held no hearing, taken no action.”

This reporting was supported by a grant from the Thakur Family Foundation. Thakur Family Foundation has not exercised any editorial control over the contents of this article.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting