“Drink, food, man, woman are the biggest desires of human existence,” says the Book of Rites, one of the five classics in the Confucian tradition, written between the Warring States period (475-221 BCE) to the Han Dynasty period (202 BCE-220 CE). If this sounds familiar, it could be because of Ang Lee’s 1994 film Eat Drink Man Woman, whose title echoes this aphorism.

The film, the tale of an aging father and his three daughters, is primarily an insight on hunger at the centre of human life – hunger for food and sexual desire. But like in the film, while food has been joyfully celebrated in most cultures, sex is hushed up or merely hinted at in daily life.

Despite this, ancient China, like ancient India, acknowledged that sex was more than mere pleasure – it is a pathway to a harmonious life.

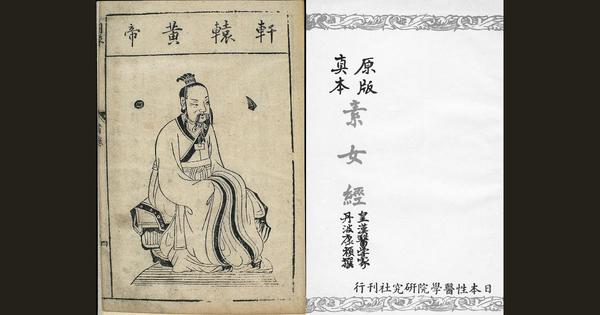

That is obvious from the Daoist text Su Nü Jing (The Scripture of the Immaculate Lady), which very well could be the earliest known text on sexology in China.

Su Nü Jing is written in a kind of FAQ format, with the mythical Huang Di or the Yellow Emperor posing questions that are answered by Su Nü the goddess of music and sexuality – or the immaculate lady.

The first exchange begins with Huang Di confessing that he has lately felt dispirited, dull and restless, along with physical unease, and asking what he should do?

Su Nü responds that these symptoms arise from a disharmony of Yin-Yang relationship between man and woman. Those who understand the principle of this sexual harmony, she explains, will lead a blissful life; those who do not shall suffer.

The Immaculate Lady then counsels Huang Di on various aspects of sex. She stresses that abstaining from sex could harm the vitality of men and the health of women.

With the understanding that the pleasure of both the partners is equally important, Su Nü explicitly advises against forceful or unwilling sex, emphasising mutual consent.

The text describes the aspects of preservation and enhancement of male vitality, recommends a variety of sexual positions, and even counsels Huang Di on family planning.

It acknowledges that a man and a woman (implicitly married) will produce children through their harmonious union, but that it should occur at the right age. Those advanced in age, it advises, should not have children even if physically capable.

A comprehensive understanding of the text reveals that it is quite concerned with educating men in the art of sex, while consistently emphasising women’s pleasure: Su Nü tells Huang Di how to identify if the woman is enjoying sex or not.

She also informs Huang Di that women possess greater vitality than men, just as water holds power over fire.

In some versions of the text, there is a section on the self-pleasure of women. Su Nü recommends that women who desire sex, may make a phallus-shaped object out of wheat flour – mentioning that size does not matter – and use it to, what can be understood as, cure the itch.

Su Nü Jing does not talk about who is an ideal man for a woman, but it does describe an ideal woman for a man in terms of her physical beauty and temperament.

Su Nü Jing may be even older than the Indian ars erotica, the Kamasutra, which dates back to the third century CE.

The Chinese text finds mention in the Daoist book Biographies of Immortals (Lie Xian Zhuan), compiled by Liu Xiang, the imperial librarian of the Western Han Dynasty, around 77 BCE.

Ye Dehui, the Chinese intellectual who is credited with reintroducing Su Nü Jing to China from Japan in the year 1907 was of the firm opinion that such works had existed in China for around 4,000 years.

He also criticised his contemporaries for having ignored their own texts on sexology, while actively embracing Western texts by introducing them to China through translation.

That this text might have enjoyed considerable popularity after it was written can be gauged through the tale of a woman named Nü Wan, recorded in Biographies of Immortals.

A part of the story reads as follows [translation mine]:

Nü Wan was a wine seller in the market of Chenzhou. Her wine was fragrant and mellow year-round, attracting many local drinkers. One day, an immortal visited her wine shop to drink, offering five volumes of Su Nü Jing [The Scripture of the Immaculate Lady] as mortgage in exchange for wine.

After the immortal left, Nü Wan opened the books and discovered that they contained lessons in the art and technique of sexual union. Nü Wan, curious enough, secretly noted down the contents of those books. She then went on to build a house, where she invited young men, drank wine with them, lived with them, and followed the techniques mentioned in those books.

Thus passed 30 years, but Nü Wan’s appearance was still of a 20-year-old.

The story ends with Nü Wan joining the ranks of the immortals.

Does the story imply that the knowledge of Su Nü Jing – and the practice of its teaching – was a path to liberation, not only for men but for women as well? With so much of importance attached to women in this text and with its authorship remaining unknown, would it be safe to assume that a woman (or women) might have a hand in its composition?

One thing that is certain, though, is that Su Nü Jing is a window that offers a glimpse of the complexities and contradictions of China, where sex remains a taboo topic for many and gender dynamics skew in favour of men. Much like in India.

Madhurendra Jha is an Indian Sinologist. He teaches Chinese language, literature and culture at the Department of Chinese Studies, Doon University, Dehradun.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting