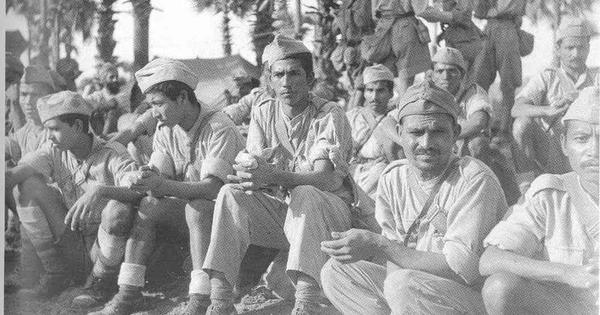

The unfortunate men were taken to various islands, such as New Guinea, New Britain, New Ireland, Bougainville, Manus, Palau, Guadalcanal, Solomon, Timor in the Pacific and Java, Sumatra, Borneo and Bali in Southeast Asia. The latter are parts of modern Indonesia, Brunei and Malaysia. The Pacific islands are all clustered north of Australia and had been captured as a base for the expected Japanese invasion of that country. New Guinea, over 300,000 square miles, is the third-largest island in the world. At that time, the western half was part of the Dutch East Indies, and the eastern half was a former German colony administered by Australia after World War I, as were New Britain and New Ireland. The others were under a mix of French, Japanese and British control before World War II. Lush tropical islands, they held horrible memories for the Allied POWs and Asian civilians made to labour in harsh conditions to fortify them for the Japanese. Eventually, over 17,000 Indian POWs were sent to the SWPA, of whom only 7,000 survived.

The voyage out was described as hell, torture or an inferno by all aboard. Crammed into suffocating holds with barely any crouching space, little food, even less water and no fresh air, they endured voyages of up to two months without knowing where they were going and when they would arrive. Scores died on the way. The journey is best described by Warrant Officer/ Clerk John Baptist Crasta, RIASC, a 31-year-old Indian Christian from Kinnigoli near Mangalore. After arriving in Singapore in 1941, he witnessed the chaos of the campaign and then the uncertainty of 1942, when he stayed out of the INA. One of the unlucky ones to be shipped out, he sailed on May 2, 1943. Crammed into the freighter Victoria Maru with 3000 Indian POWs in holds divided with planks of wood into spaces three feet high, one could enter and exit only by crawling. He called it a “Torture Ship”. The floor space for each man was three feet by one foot, so they could not sleep. It was suffocating, dark, stinking and hot with the boiler nearby. “Could Inferno be worse?” he asked.

The convoy sailed slowly south, and they were given a handful of rice, some dry fish and a cup of water twice a day. The Japanese said that as they were resting, they needed less food. Crasta did not mind the meagre food, but with two cups of water a day, “one might die of thirst”. If they tried to go on deck, they were beaten.

On May 4, the Japanese asked for stool samples. With so little food, it was difficult to pass motions. Besides, with six latrines between 3000 men, it took too long. The medical officers were thrashed for this delay. One POW had a brainwave and asked the sweepers to collect whatever was in the latrines as material. The Japanese were pleased at getting the samples, not knowing how they had been made. Due to this random sampling, many fit men were marked as sick and offloaded at the next port. Unfortunately, due to the random nature of this, several of the sick ones had to stay on. On May 12, they docked in Surabaya in Java and were allowed to disembark. They could bathe in the sea and a nearby swimming pool and buy food at cheap prices from the locals. They hoped they would stay on, but when they once again refused to join the Japanese, were shipped off on May 14. The water ration was reduced to one cup per day. Crasta summed it up perfectly when he asked, “Could humanity be degraded to such an extent? Could providence be so cruel?”

The queue for water began at 6 am and took hours. One day, when his turn came at 10 am, the water had run out. Crasta went begging all day for a sip of water; he could barely speak. The next day, he lined up early, but the queue was huge. In desperation, he hoped for an Allied attack by plane or submarine so he could die, and his misery would end. While he was thinking this, a pipe in front of him sprung a leak, and water poured out. Providence had sent him water instead of a torpedo. He had his fill before a huge crowd gathered.

Then, dysentery broke out on the ship. Men began dying every day. Wrapped in a worn-out blanket, they were lowered into the sea, unsung. He said, “The scene was pitiful … Brave, virile soldiers … were now helpless like babies.”

On they went, with no timeframe or destination being told to the Indians. On May 28, they reached Palau, an island north of New Guinea. Hoping to be allowed out, they were kept on board for 12 sweltering days. When they got the welcome order to disembark, just 200 men had gotten off before the order was reversed. The lucky 200 were able to bathe in the sea before returning. They stayed put for another week, but conditions grew worse. The Japanese asked them to wait for ten days, and they would be served good food. Fortunately, water was increased to three cups daily, and they were given a seawater bath on deck – the first in one and a half months. It felt heavenly. Finally, on June 23, 1943, after one month and 26 days of this misery, they reached Rabaul in New Britain.

Once they had arrived, there was no rest. The men had to unload the ship, which was back-breaking work with heavy loads that took days. Then they had to walk to their camps, often miles away, and once there, had to make their own huts with little or no material provided. Ants, mosquitoes and earthworms became their companions. It rained incessantly, without warning and sometimes for hours without stopping. They were always wet, and malaria became endemic. Food, drinking water and medicines remained as scarce as before. Crasta said that soon after reaching there, in July 1943, he contracted malaria. When he shivered with cold, he only had a thin cotton blanket. When he burned with heat, he would pass out and wake up in a sweat. There were few to tend to him, as all the fit men were working.

The sick were treated with great suspicion and disdain by the Japanese. In the diarist Captain Patel’s camp, one day, the senior Japanese commander, Colonel Takano, inspected them. Most were barely able to stand. Touching each one’s forehead, if he found it hot, he slapped them and sent them back into the sick hut. If not, he kicked them and sent them off to work. This camp was 3 miles away from the work area at the Wewak aerodrome, so the men had to walk six miles a day, besides doing the harshly disciplined work. They left at 5 am and returned at 6 pm. Some of the sick who had been forced to work took much longer.

In Crasta’s camp on October 12, 1943, they witnessed their first major Allied air raid. After running away to hide on a hill, he saw hundreds of bombers pounding the harbour and the town for an hour. The earth shook, and he wondered if the “Day of Judgement” had come. After it was over, when he returned to camp, he found men running helter-skelter rescuing dozens buried in collapsed trenches and huts. Soon air raids happened day and night, and they just had to get used to it.

As 1943 came to an end, the Indian POWs were desperate. So far, they had largely seen only the might of the Japanese empire, and though the incessant bombing indicated the strength of the Allies, so far it had only meant death and horror for them. In fact, some referred to them as enemy planes. There was no sign of any Allied invasion of the islands they were on. But unknown to them, a strategic shift had occurred. The year 1942 had seen the Japanese rampant over Asia, but starting from February 1943, when they had to evacuate Guadalcanal, the first territory they lost, they were on the back foot. The US war machine had sprung into action, and millions of men were armed and trained; thousands of planes and hundreds of warships were built. The Allies began their island-hopping campaign with the first strategic goal being the Philippines, attacked in 1944. Then they were to move north to Japan, island by island. But first, they cut off the SWPA from the Japanese supply route so they could not be attacked from behind, which meant that for Indian POWs, things would get worse before they got better.

With supplies cut off, the already precarious food and medical situation deteriorated. Nothing they needed was available here except coconuts, and now the Japanese forced the men to improvise and somehow live off the land no matter what. With dysentery treated by chewing burnt copra ash, malaria untreatable with little quinine, fermented coconut oil and water used for beriberi, jungle rot simply swabbed with mercurochrome, and bandages reused multiple times till they just fell apart, the situation was dire. Rice rations became even smaller, and the men ate grass and chewed leaves just to fill their stomachs. The 35-year-old Naik Gopal Pershad Jha from Banka in Bihar, who served in the Indian Army Ordnance Corps and was in nearby Bougainville under similar conditions, carefully documented the diminution in rations: “In Malaya in 1942 [we] received 16 oz of rice or wheat a day. In Bougainville … from November 1943 the ration gradually fell, to 9 oz in May 1944, 4 oz in July, 2 oz in August until in 1945 the prisoners were surviving on plants they could forage from the jungle.”

Another result of this was that the Japanese resorted to cannibalism. Captain Patel noted in his diary that on June 14, 1944, Havildar Sohanlal and Sepoy Hansraj of the 3/17 Dogra Regiment were ‘taken away by two armed Japanese saying that if anybody (PW) accompanied them anyone who came will be given rice. They never returned, probably ate them”. Later, when more were invited, no one went. This act was not witnessed, though others were and taken to trial after the war. For the moment, the POWs were living through hell.

Excerpted with permission from The Forgotten Indian Prisoners of World War II: Surrender, Loyalty, Betrayal and Hell, Gautam Hazarika, Penguin India.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting