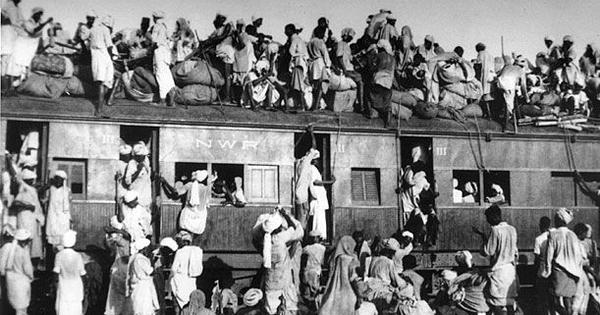

The residents of Lahore woke up that morning to the sound of great bustle and movement along the road. For more than three hours, they watched the organised evacuee party of Hindu and Sikhs on its way to DAV College where the main camp had been set up. Men, women, and children with their few movable earthly belongings, hundreds of donkey carts, bullock carts and camels formed the caravan. A flying military jeep patrol shepherded the procession, which was accompanied by lorry-loads of troops of the Baloch Military, which had joined as they approached the tense areas of Lahore. The route diversion, river crossing, and a sense of panic among the people had slowed them down and they took an extra day to reach Lahore.

The Batra family had now travelled for eleven days on foot to reach this camp. The journey had not been less than a passage through the river of fire. Yet, they considered themselves lucky that they were not among the one million killed. All evacuees were hastily crammed in the DAV College camp where local evacuees were also staying, waiting for their final evacuation.

Kesar Dass went looking for Padam Singh. He wanted to thank the officer personally but the officer was nowhere to be found. He learnt that after depositing their kafila, Padam Singh had left to secure another convoy, continuing to address a human catastrophe of unimaginable proportions.

The DAV camp was protected by military pickets. People were starved and fatigued. There wasn’t much ration left at the camp, and the migrants had to once again be content with boiled lobhia. Many evacuees were still making their way to these camps from the hinterland. The scene at the refugee camp was one of both despair and resilience, a poignant snapshot of human endurance amidst the chaos of Partition. There were three doctors to tend to the thousands wounded.

It had not rained for two days. At dusk, a few men lit a bonfire in a corner of the college playground. Similar fires had been lit by many other groups. They sat around the fire, its flames casting flickering shadows on the faces huddled around it. The fire provided warmth against the chilly night air, but its light also seemed to illuminate the collective trauma etched on the faces of those gathered. Men, women and children sat close, their tattered clothes and weary expressions telling stories of unimaginable hardship. The air was thick with the scent of smoke and the faint aroma of whatever meagre food they had managed to cook over the flames. Everyone had brought whatever food they had to share with others. Punjabis prioritise others’ needs and comfort over their own, readily sacrificing their meals to feed others. Often, the best food is left for others and served with love. This culture of giving reflects their deep-rooted values of community, compassion, respect and unparalleled hospitality. This spirit was maintained even during the most telling times of migration.

As more people joined, an elderly man, his face lined with exhaustion, recounted how his village was set ablaze, forcing his family to flee with nothing but the clothes on their backs. His voice trembled as he described the long, treacherous journey, the constant fear of attacks, and the heartbreak of leaving behind a lifetime of memories. A young woman, clutching a sleeping child to her chest, spoke next. Her eyes were hollow, her voice barely above a whisper as she narrated how her husband was killed in front of her during the journey. She had no time to grieve, she said, as she had to keep moving to protect her child. Her story was met with silent nods and shared tears, a grim acknowledgement of the atrocities they all had witnessed. Another man, his arm bandaged from a recent injury, recounted the hunger and thirst that plagued their journey, the days spent without food or water, and the desperation that drove some to even drink from muddy puddles. A young boy, no older than fifteen years, spoke of how he carried his younger sister on his back for miles, refusing to let her go even when his legs felt like they would give up. His bravery drew murmurs of admiration from the group, a rare moment of pride amidst the grief.

As the night deepened, the stories continued, each one a testament to the resilience of the human spirit. As they shared their overwhelming sorrow, a sense of solidarity built among the group. The bonfire became a symbol of their shared suffering and their determination to survive. It also served as a reminder of the homes they lost. As they sat together, sharing their stories and their pain, they found solace in each other’s company. With its flickering flames, the bonfire became a space of healing, a place where they could begin to process their collective trauma and find the strength to face an uncertain future.

They had to stay at that college camp for four days. Most men volunteered to help the newly arriving columns by the third day. The women were taking turns to cook and serve whatever grains or food was distributed. Young boys attended to the elderly. Amidst the ruins of their lives, the evacuees in the camp were not just survivors – they became a community bound by shared suffering and an unyielding will to endure.

Kesar Dass, who had also enrolled himself to volunteer, stood at the gate on the third day, waiting to receive a kafila. He had heard that the kafila had many people from Jhang. He saw the column come in around noon. Like their own column, this too was miles long. It was hard to accommodate them in the already crammed camp but everyone generously made room for them.

Ram Lal sat on the floor next to where Kesar Dass stood keenly looking for a familiar face in the incoming deluge of evacuees. He heard someone call his name. The voice sounded familiar. He looked around and spotted Radhe Shyam, the postman from Rodu Sultan, waving at him as he tried to squeeze his way through the crowd.

“How are you, Chacha-ji?” Radhe Shyam asked, bending to touch Ram Lal’s feet. “How is everyone?”

“Jeonda rah, I am so happy to see you, Radhe Shyam. We have been worried about you,” Ram Lal said, blessing Radhe Shyam with a long life.

Radhe Shyam sat down next to him. “The last few days have been a nightmare. Everything changed after you left, Chacha-ji. All Hindu families in the village, who did not leave with you, also left. Only Krishan Lal Halwai, who lives next to the small temple at the far end of the village, refused. He said no one was going to hurt the old man and his wife.”

Krishan Lal was a bawarchi in the house of a British officer posted in Bhopal for a long time. When both his sons grew up, the elder found employment under his tutelage in the same kitchen, while the younger one left for Lahore to try his luck in the film industry. Krishan Lal quit his job and returned to Rodu Sultan. He set up a business of cooking food and sweets at weddings and festivals. His food was popular all over Jhang, particularly in towns, as he could cook many English dishes. His sons never visited them. After he and his wife turned old, they gave away their business to one of their employees and spent time looking after the temple, cooking for the travellers who stopped to stay overnight nearby.

Radhe Shyam continued, “Some of us sneaked back into the village two days later to feed our cattle. Fortunately, the old couple was unharmed. They told us that after we left, the village was attacked late in the night by a large mob. Mukhtyar and his men put up a good fight, the mob left but not before they had set a few houses on fire near the outskirts. I went around the village to check out, everything seemed to be where we left.” Radhe Shyam sighed. “We were still trying to comprehend what to do when a band of men arrived suddenly from nowhere in three jeeps. I hid myself behind a heap of hay in one of the houses. All of them were armed with guns. They drove through the village shouting, ‘Leave or die. All non-believers must leave this holy land of Allah.’ Some fired in the air. They then sped away towards your house. Mukhtyar and his sons went after the miscreants. A few minutes later I heard gunshots again. The firing went on for a good thirty minutes. It was still on when I left the village.”

Radhe Shyam looked at Ram Lal. His face had suddenly turned stark white, drained of all blood. Looking at Ram Lal’s state, Radhe Shyam decided against continuing any further. “I have to go now, Chacha-ji. I am searching for my wife’s younger brother who got separated from us. After that my family will head to Hansi. I will see you somewhere in Hindustan.”

As he turned to leave, Ram Lal inquired in a feeble voice, “Is Mukhtyar fine? Is our house safe?”

Radhe Shyam heaved a deep breath. He answered hesitantly, “If you insist on knowing … I was scared, so I slipped out and escaped through the fields. But Sukhi Chand, the pandit, met me a few days later. He told me that he too had hid himself in the fields when the firing started. These men had come to seize your house and property. From where he was hiding, the pandit could see Mukhtyar and his sons firing on the people inside your house. The firing stopped after an hour. He also saw an injured Mukhtyar put Alam’s dead body in the jeep and leave. It appeared that they had ran out of cartridges; Mukhtyar lost his son trying to evict them from your house. He is himself critically injured. What a sincere and brave friend you have, Chacha-ji. I was reluctant to tell you but you…”

Ram Lal was no longer paying attention to Radhe Shyam. He was devastated. He was already a broken man, and the news of his friend losing his son and getting injured and that, too, trying to protect his Hindu friend’s property, had shattered him. A searing agony gripped his heart on learning that their sacred home, the sanctuary where a thousand memories were forged, had been forcibly occupied. Tears of anguish filled his eyes. A fire of rage burnt within him. Ordinary people like him had become pawns in a larger game of power and prejudice. Suddenly, he felt a piercing pain in his chest. He knew he was having a heart attack. Before Ram Lal could call for help, he collapsed.

Excerpted with permission from Kafila: A Jhangi Family’s Partition Memoir, Sumant Batra, Om Books International.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting