It was a harsh winter morning in October 2019 in a Jammu village, when Makhno Devi took her 11-year-old son, Rutav, to the nearest sub-district hospital.

For three days, Rutav had stopped urinating, his body temperature had risen and he was refusing to eat.

But doctors at the hospital in Ramnagar town struggled to treat the boy. By evening, they referred him to the district hospital in Udhampur and gave Makhno an ambulance.

Udhampur was 36 km away, a ride over hilly terrain. Rutav died on the way.

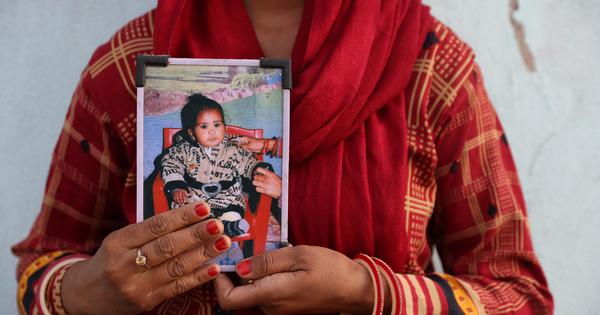

Thirty-eight-year-old Makhno, who grows maize on a small farmland in Kirmoo village, said that the ambulance driver left the family on the road with the body. For the next three months, no health team visited her to ask about Rutav’s death.

Then in February 2020, she was told that her son’s death had been caused by a contaminated cough syrup she had forced him to gulp down for three days, a syrup she had bought off the counter from a chemist in Ramnagar.

Thirteen more children died in Jammu’s Ramnagar district after Rutav – all of them had consumed Coldbest-PC cough syrup. Six who survived were left with permanent disabilities.

The syrup had been manufactured 500 km away in Himachal Pradesh’s Sirmaur district by pharmaceutical company Digital Vision.

Makhno’s statement was recorded by the local police. That was all. She did not get any compensation, since Rutav’s death occurred on the road with no medical certification.

Rutav is one of 172 children who have been killed since 2020 by contaminated cough syrups manufactured by Indian pharmaceutical companies. The deaths have been reported from India, The Gambia and Uzbekistan. Even censure from international agencies like the World Health Organisation has failed to stop the deaths.

Most recently, 22 children in Madhya Pradesh’s Chhindwara died after having cough syrup that had been adulterated by the toxic industrial solvent, diethylene glycol, which led to kidney failure in the children – the same solvent that had led to the deaths in Jammu.

Over the last few weeks, as Makhno heard of the deaths in Chhindwara, it seemed to her as if nothing had changed. “Even after our children died, if this is happening, what was the government doing?” she asked.

Makhno said she has no hope that the Himachal Pradesh manufacturer responsible for her son’s death will be punished. Her pessimism is not without basis.

Since 202, four different manufacturers have been held responsible for using the toxic industrial solvent, diethylene glycol, in the syrups that led to kidney failure in the deceased children. Three of them are still in businesses.

Scroll went back to the Jammu families who lost their children in 2020 to find a recurring pattern of injustice – cases stuck in an excruciatingly slow judicial system, pharmaceutical companies that get away.

The firm, Digital Vision, has not only gone on to resume production, but found guilty of more drug quality violations, data accessed by Scroll shows. But the trial against it in the 2020 case has not proceeded because of a stay order by the Jammu bench of the High Court of Jammu and Kashmir.

“I keep remembering him,” Makhno said, talking of Rutav, her first-born. “We didn’t get justice.”

Delay in detection

Two months after Rutav’s death, Murfa Begum, a 25-year-old from a village in Ramnagar district in Jammu, lost her three-month-old child. The infant died after consuming two doses of the toxic Coldbest cough syrup.

Begum alleged that for several weeks, the health department did not respond. “We cried, we raised the alarm but they began an investigation too late,” she said.

The Ramnagar district administration began testing water samples, food grains and blood samples only in January 2020 – three months after the first death. “By then more children were dying,” Murfa said.

On February 17, 2020, Chandigarh’s Regional Drug Testing laboratory found that samples of Coldbest had 34.34% of diethylene glycol, which causes kidney failure in children.

“Ye to katal hua,” said Murfa. This is murder.

A similar delay was seen in Chhindwara where it took a month for the district authorities to suspect a contaminated cough syrup was causing the deaths of children.

A slew of first information reports were filed in Ramnagar, Ambala and Sirmaur. The FIR in Ramnagar invoked sections involving culpable homicide not amounting to murder, adulteration of drugs, sale of adulterated drugs, and causing grievous hurt and several sections of the Drugs and Cosmetics Act that deal with sale of harmful drugs and its punishment.

The accused included the Ambala-based owners of Digital Vision, Purushottam Goyal and his two sons Konic and Manic Goyal, the company that distributed the cough syrup and the chemist who sold it. The state drug controller also registered four cases of drug safety violations against Digital Vision.

A social activist from Jammu who followed these cases, Sukesh Khajuria, said the Goyals got bail within an hour of arrest while the chemist’s bail kept getting rejected. “The rich and powerful always get away,” Khajuria said.

The company that got away

Ashok Kumar obsessively watches the last video of his son Aniruddh, from January 2020. It shows the two-year-old in a hospital in Jammu, and his mother trying to distract and feed him.

Aniruddh caught a chest infection in late December 2019. By then accounts of children dying mysteriously had already flooded households, Kumar, a government school teacher in Ramnagar town, said.

Like Makhno, Kumar had also gone to the same chemist for medical advice. “There was no child specialist in Ramnagar. So we all used to go to this one chemist who prescribed drugs,” Kumar said. Aniruddh was administered Coldbest syrup for two days. By the second night, he began vomiting and getting loose motions.

Ashok Kumar took his son to three different hospitals before he arrived at Chandigarh’s Post Graduate Institute. He died of acute kidney injury and a brain haemorrhage soon after.

Kumar was one of 12 families that received compensation of Rs 3 lakh. But he seeks more. “I want those accountable to be punished,” he told Scroll.

What enrages Kumar is that Digital Vision, the manufacturer of Coldbest, continues to make drugs. The firm has branched into making antibiotics, antioxidants, protein powders, analgesics, and orthopaedic medicines, according to its website. Its products are exported to Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, Nigeria, Sudan, Ghana, Congo, Myanmar, Nepal, Cambodia, Vietnam, Ireland and Spain.

Digital Vision did not respond to an email asking them what corrective steps they had taken after the Jammu case.

Tellingly, the company had been red-flagged even before the Jammu deaths.

Between 2012 and 2020, 12 drugs manufactured by the Himachal-based firm, including syrup-based formulations and tablets, were found to be “not of standard quality”, shows data accessed by Scroll from an online database on which state drug controllers report cases of substandard drugs. Not all states are meticulous about uploading this data on the portal.

Moreover, even after the Jammu deaths, on five different occasions, officials from Maharashtra’s food and drug administration found Digital Vision’s drugs to be of “not of standard quality” during random tests.

Of these, Azithromycin oral suspension, a common antibiotic it produced, was found to be of “not of standard quality” on three occasions.

Maharashtra’s joint commissioner of drugs, DR Gahane, told Scroll that they had issued a showcause notice to the manufacturer and informed the Himachal Pradesh drug controller about the violations.

Asked about action taken against the firm, Himachal Pradesh’s assistant drug controller Sunny Kushal told Scroll he is “not interested in discussing Digital Vision”.

As recently as December 2024, the Himachal Pradesh excise commissioner in an order reported that the firm was manufacturing morphine tablets without a proper licence and exporting it to Sri Lanka. It notified the state drug controller to look into violations under the Drugs and Cosmetics Act. Scroll has seen the order. Kaushal did not respond to Scroll’s messages on the action taken.

Meanwhile, the firm continues operations. Sushil Yadav, general manager, marketing, at Digital Vision, refused to comment on the violations. The company did not reply to an email.

Slow trial

The slow judicial process has also thwarted the course of justice for the Jammu families.

In 2023, three years after the deaths of the children, a 742-page chargesheet was filed by a Special Investigation Team tasked with the probe and the trial began in Udhampur sessions court.

In February 2024, the sessions court judge asked certain aspects of the case to be investigated further. In March 2024, the manufacturer approached the Jammu High Court for a stay on reinvestigation. The court granted its request.

“Since then, the case is stuck,” Khajuria said. “Every time there is a hearing, their counsel mentions the High Court stay and a new date is given,” he said.

The stay has also affected the trial of cases against Digital Vision lodged by the Food and Drug Administration in a special court in Jammu meant for cases filed under the Drugs and Cosmetics Act. A drug official said they have submitted objections but the trial is dragging on.

“Sometimes for simple prosecution cases, it can take 15 years or more for conviction to come,” the drug official said.

Khajuria said that he had approached the National Human Rights Commission to seek compensation for the families of children who died.

In 2021, the NHRC directed Jammu and Kashmir to pay Rs 3 lakh compensation. This was immediately contested by the state at the High Court but their petition was dismissed. Later, the state government appealed to the Supreme Court.

In a judgement by the apex court in November 2022, a two-judge bench observed that “it was specially found that the officers of the drug and food control department were negligent and therefore ultimately the state will be liable to pay compensation”.

“Your officers are found to be negligent. They ought to have been vigilant. Don’t compel us to say things about food and industry department. They don’t perform duties at all,” the judges observed, PTI reported.

Despite the strong words from the court, no action has been taken against drug inspectors in Jammu.

Drug inspectors are bound to inspect a manufacturing unit at least once a year to ensure compliance to rules. But as a parliamentary standing committee report on chemicals and fertilizers pointed out last December, there is a 60% vacancy in sanctioned posts of drug inspectors – 303 out of 504 are vacant.

High vacancies affect not only the number of inspections a drug inspector can undertake but also the number of convictions. The same report found out that between 2015-’16 and 2018-’19, of the 2.3 lakh drug samples examined by state drug controllers, 593 were declared spurious and 9,266 were of substandard quality. But that resulted in only 35 convictions by the courts – a rate of 5.9%.

However, former drug controller of Himachal Pradesh Lotika Khajuria told Scroll the department in fact worked “promptly to gather all evidence against Digital Vision and filed a case”. But the parents of the children who died question the government’s intent. “The investigation in this case is not satisfactory,” Kumar, the schoolteacher, told Scroll. “It is an eyewash.”

Disabled for life

At least six children who survived the deadly cough syrup in Jammu live with multiple disabilities.

Sapna Kumar was less than a year old when she had the Coldbest syrup in 2020.

She survived but has 40% disability. She has difficulty in movement, moderate intellectual impairment and disability in vision and hearing.

Pavan Kumar was in hospital for over three months in 2020, after consuming the cough syrup, of which 50 days were on ventilator support.

Now seven years old, the child has partial vision, high blood pressure and cannot hear from one ear, his father Shambhu Ram told Scroll.

“We have to visit Chandigarh’s PGI hospital every month. I have to borrow money regularly for his treatment,” Ram, a daily-wage labourer, said.

None of the children who were disabled received any compensation. “This is the value of a poor person’s life in India,” Ram said.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting