In South Kolkata, as the Hooghly River bends toward the Bay of Bengal, there lies a neighbourhood that carries within its name at least three distinct origin tales. Kidderpore has long been absorbed into the former British capital, but the history of its many names tells one story: how communities understand their place in the city and make sense of themselves in relation to the world.

The most enchanting of these three tales is drawn from religious literature. Across the Quran and Islamic literature, the figure of Al-Khidr or Khizr, is a wanderer who appears as a guide. Through divine intervention, he appears to travellers or sailors when they are faced with impossible odds at sea.

Khizr also makes a place for himself in Bengali folk tradition, particularly in the mosaic of river worship and maritime spirituality, thus lending his name to “Khizarpur”.

The second origin story emerges from British mercantile power while the third narrative has its roots in the Bengali linguistic tradition and Hindu devotion.

Rather than viewing these competing narratives as historical confusion, they offer a window into how communities create and preserve meaning around the places they inhabit.

The wanderer

In Surah 18 of the Quran, or the Surah Al-Kahf (the Cave), one of the prophets, Moses, comes across an unnamed man during his travels, whom Islamic scholars identify as al-Khidr. But they disagree on his nature. Some like al-Tabari – or Ibn Kathir as he is also known – place al-Khidr among the legions of prophets, while others regard him as a saint.

Islam is not the only religion where the mysterious figure makes an appearance. The historian Arent Wensinck claims that the unnamed servant of God mentioned in the Quran is based on the Jewish legend of Rabbi Joshua and Elijah. But Brannon Wheeler, a professor of religious studies, argues that it is the opposite, where the Jewish legend draws from the Quranic verses.

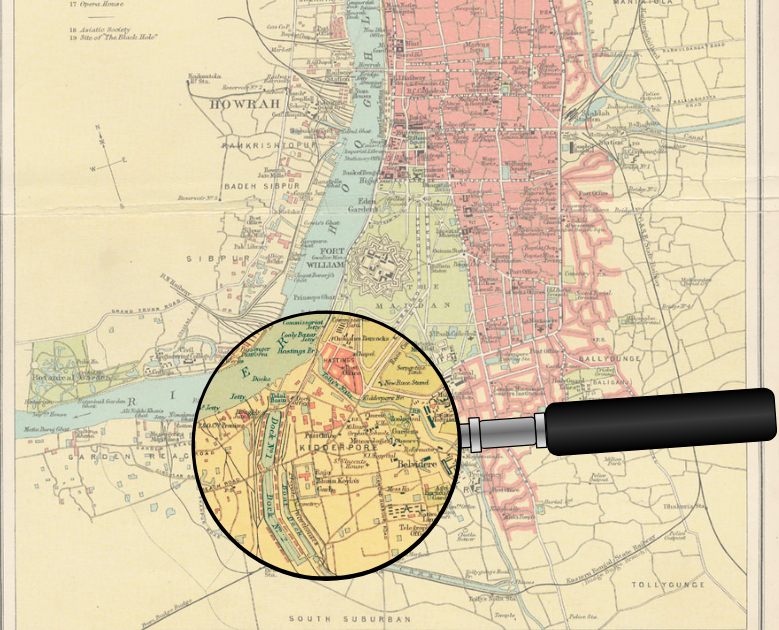

Medieval Jewish mystical texts describe encounters with this eternal wanderer at crossroads and bridges, liminal spaces between worlds. A look at the map elucidates how Kidderpore sits neatly at such a threshold, where river meets land and the Hooghly flows onwards toward the Sagar Islands, until it meets the Bay of Bengal.

Historical accounts of Bengal refer to local veneration for al-Khidr.

The West Bengal District Census Handbook of 1961 takes note of an old ceremony in Murshidabad, which it refers to as “the Bera or the festival of Khwaja Khizr”.

Charles Stewart, an officer of the East India Company, in his History of Bengal, similarly notes: “The eastern parts of Bengal are intersected by rivers and creeks…the veneration of the inhabitants for the tutelary deities, who are supposed to preside over the rivers and waters, is carried to an extreme, both by Hindoos and Mohameddans…the present governors are obliged to comply with the superstition of their subjects by making, at Dacca, an annual offering to Khwaja Khizr (supposed to be the Prophet Elias).”

There are contradictory accounts of how the practice began. One says it was first started by the Nawabs in Murshidabad on the Bhagirathi in the western part of Bengal around the 18th century. Another suggests that it was started in Dhaka on the Padma river by a Mughal subedar by the name of Mukarram Khan much earlier, around the late 1620s. What is common is that it is viewed to have been a community practice before being adopted by the elites.

The first narrative, thus, situates Kidderpore as Khizarpur.

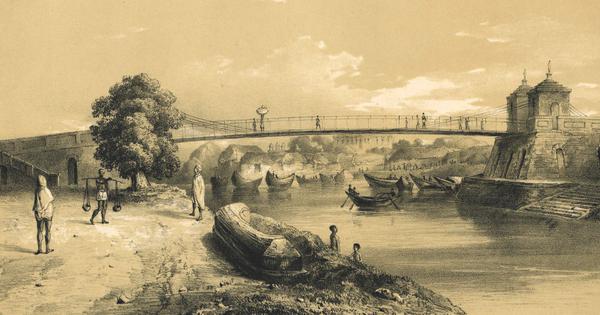

This story carries weight considering how Kidderpore and its history predates that of Calcutta itself, as the East India Company’s records from 1709 mention complaints against local police chaukis in the area. Before the British transformed the area into a port suburb, the stretch of land served as a home to communities whose lives were intricately woven with those of water, boatsmen, fishermen, and traders who would perhaps find solace by invoking Khizr and his protection for safe passage over the torments of the river and the seas.

Colonel Kyd or Kyd and Company?

Walking away from the world of faith and folktales towards colonial administration, the second origin story of Kidderpore can be traced to the British who had begun transforming the area into a trading hub.

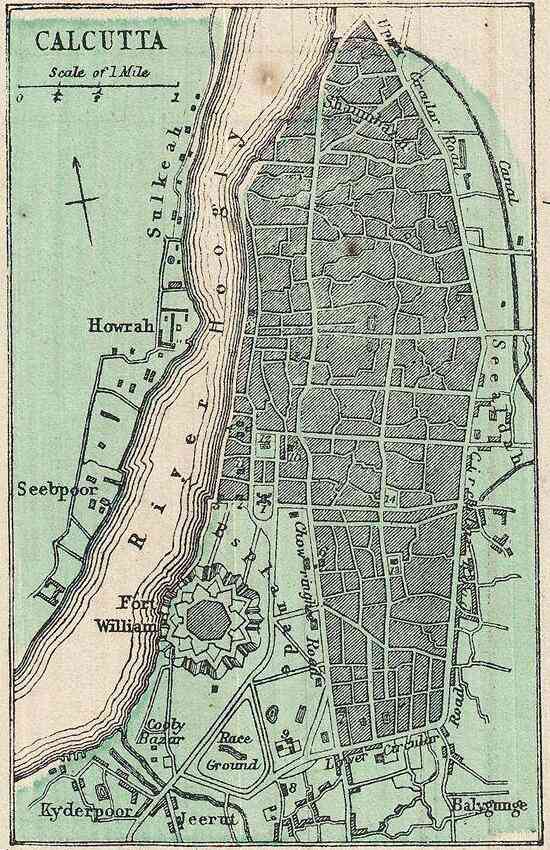

Some accounts trace Kidderpore to a Colonel Robert Kyd, who is credited with establishing the Botanical Gardens. But the timeline does not align with historical evidence as Kidderpore can be found on maps of the Hooghly as early as the 17th century, way before Kyd arrived, according to historian PT Nair.

The other narrative of James Kyd of Kyd and Company finds more solid ground as the ship-building firm was instrumental in establishing the Port of Calcutta. In 1827, an entry in the Asiatic and Monthly Register for British India and its Dependencies suggests that Kyd and Company were the owners of the dockyards at Kidderpore, thus lending credence to this colonial etymology.

The transformation of Kidderpore into a major port facility began in earnest in 1884, when it was selected as the site for Calcutta’s wet docks, fundamentally altering the character of the neighbourhood, bringing it under the control of the Calcutta Port Trust and connecting it to global networks of trade and commerce.

The construction of the docks required displacing existing communities, which also included wealthy families, such as the Ghoshals, who were Zamindars and had been in the area for over three centuries. The patriarch of the Ghoshal family had built the Bhukailash Rajbari along with twin Shiva temples, creating a space for Hindu devotion that intersected with landed aristocracy.

Anglicised pronunciation

Finally, according to the third story, Kidderpore is but an anglicised pronunciation of Kedarpore, which loosely translates to the settlement of Kedar, one of the several epithets of Shiva. According to historian Nair, it made sense for Shiva to have a place near Govindpur in the Maidan since the altar of Kali was situated there, thus the proximity between the goddess and her consort.

The Bhukailash Shiv Mandir is home to an 11-foot-high Shivalinga, which is carved from a single black stone, supposedly the largest on the continent, that further substantiates this theory.

Another folk etymology suggests a rather comical origin: British officials in Bengal would use broken Hindi to ask for directions to the port where their ships were harboured, and their inquiries would sound like “kidder-port” to the locals. (A similar theory claims how a British official, due to his accent and miscommunication with a location, started referring to Kalikata as Calcutta.)

Colonial port to Kolkata neighborhood

In 1888, the Suburban Municipality was amalgamated within the Calcutta Municipal Corporation under the Calcutta Municipal Consolidation Act, which led to Kidderpore becoming a suburb of Calcutta. Though it reflected the growing importance of the neighbourhood to the colonial economy, it also set off a gradual erasure of Kidderpore’s distinct identity as communities were displaced and older ways of life gave way to industrial demands.

Walking through Kidderpore today, all three layers of these histories are visible, especially in its architecture and infrastructure. The renowned collapsible bridge built to enable passage for the ships into Garden Reach dockyard remains operational to this day. It is a practical necessity and a reminder of the expansionist dreams of the British.

The wide roads constructed to ease the transportation of heavy goods still serve their original purpose, as cargo trucks throw up dense clouds of dust while navigating between warehouses and shipping facilities. The old, red-brick buildings that once housed port officials and customs officers stand as monuments to colonial administration, while the presence of the South Port police station in its original quarters maintains institutional continuity across political transformations.

The area’s literary heritage adds another dimension to its identity. Its streets named after poets like Hem Chandra Chattopadhyay, Michael Madhusudan Dutta and Rangalal Bandopadhyay, reflect its designation as Kabitirtha, the sacred space of poetry. The residence of Woomesh Chandra Banerjee, the first Congress president, is a reminder that Kidderpore was not merely a space of commerce and devotion but also of political awakening and nationalist sentiment.

Perhaps the most telling aspect of Kidderpore’s contemporary character is how little photography is permitted in many zones owing to port security concerns, transforming the neighbourhood into a space that resists easy documentation or touristic consumption, preserving something of its working-class identity and operational importance.

The maze of narrow bylanes is lined with densely-packed housing for daily-wage labourers, small stores selling gold and silver jewellery, biryani restaurants and beauty parlours – all of which create a living landscape that exists in tension with its historical narratives.

The renowned Solana Masjid harbours its own story of inter-community relationships and economic exchange. It is said to be named after an incident in which a wealthy Hindu woman sold the land to a Muslim priest for a sum of solaa anna (16 annas). These stories of practical accommodation and mutual dependence blur neat divisions between historical periods and communities, with all of them intermingling and being in a state of flux.

The multiple origin stories of Kidderpore enable one to understand how places accumulate various meanings across the community and time.

Each etymology serves specific needs and ideals of belonging for the inhabitants, be it the mystical figure of al-Khidr, Colonel Kyd, or the figure of Kedar. The stories also gain currency as valuable notions of cultural preservation, maintaining connections of being across time and space, commercial and devotional, colonial and indigenous, or even mystical and practical.

Ankush Pal is a sociologist trained at the London School of Economics and Political Science who researches and writes on public space, South Asian culture and urbanisation.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting