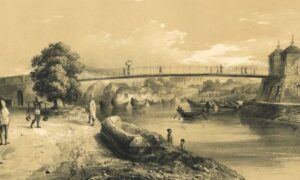

Cuttack is my hometown. For most of my life, it stood apart from the contagion that swept across India – a city devout yet not doctrinaire, religious not rigid, where the sacred did not demand purity or exclusion as its price.

Nowhere is that spirit more visible than in Buxi Bazar, where the Amareswar temple shares a wall with a dargah, and both overlook Royal Biryani, one of the city’s most famous eateries. On festival nights, incense, attar and mutton smoke mingle in the same air. Amid these ordinary miracles of coexistence, Cuttack learned to live with itself.

In June 2024, the city elected Sofia Firdous, a young Muslim woman, as its legislator – a decision so natural that few even called it historic. Cuttack’s pluralism was routine, built into our mental architecture as much as the 1,000-year-old Barabati Fort. It was as quintessentially Cuttacki as the timeless pleasures of a good dahibara aludum.

Muslim artisans fashion the silver medhas that rise each autumn behind the goddess’s face. Their needles, threading gold and silver, turn labour into liturgy. For them, Durga is a civic icon to be adorned, a goddess who belongs to the whole city. The shimmer of their craft is Cuttack’s oldest theology: faith shared is faith strengthened.

Centuries before anyone spoke of secularism, Odisha’s devotion had already found its own grammar of coexistence. The 17th-century poet Salabega, born of a Muslim father and Hindu mother, composed bhajans to Jagannath as tender and iconic as the oft-performed Ahe Neela Saila: neela saila, or blue mountain alludes to the Puri Jagannath Temple and is the title of perhaps Odia literature’s greatest modernist masterpiece, penned by the great Surendra Mohanty.

A Muslim singing paeans to a Hindu god, and accepted as devotee, not an outsider, was unremarkable. Salabega’s verses described longing as the truest form of worship; distance, not proximity, made faith pure.

Indeed, Jagannath, the state’s presiding deity, embodies this harmonious spirit. He is a god who dies and is reborn every 12 years in a ritual where Brahmins and Dalits, even Muslims and Christians, touch the same chariot. To remember Salabega now is to realise how far we have drifted from Odisha’s spirit. And in what short order.

Broken glass

In 1992, when the Babri Masjid was demolished and communal riots broke out in many parts of India, Cuttack remained calm. Its temples and dargahs were separated only by narrow lanes, not fear. Firdous’s election as Cuttack’s first Muslim woman MLA barely months after the inauguration of the Ayodhya Ram temple in a city that is 89.65% Hindu seemed further proof that old immunities still held.

But on the night of October 5, that equilibrium was disrupted. During the annual immersion of Durga idols, slogans turned to stones and glass bottles. Within hours, Odisha’s millennium city lay under curfew and the internet was restricted for 48 hours. Fortunately, the police were able to control the Bajrang Dal workers, so there were no deaths.

For a city that had never known communal rioting – not in 1947, not in 1992, not even in the aftermath of the violence against Christians in Kandhamal in 2008 – the violence in early October felt like an ontological rupture – as if the very nature of Cuttack’s being was being questioned anew. It was like mirror had shattered, showing a face we did not know we possessed.

VIDEO | On Cuttack violence, Barabati-Cuttack MLA Sofia Firdaus says, “The brotherhood we speak of in Cuttack is not just a word, it’s our way of living. That’s what makes Cuttack different from other places. We strongly condemn the unfortunate incident that occurred, and the… pic.twitter.com/SjJYPfbIXR

— Press Trust of India (@PTI_News) October 6, 2025

The collapse of neutrality

For nearly a quarter-century, Odisha seemed immune to communal violence between Hindus and Muslims, which has become increasingly common in many parts of India. Chief Minister Naveen Patnaik’s long technocratic rule had built a culture of calm competence – disaster management, roads, electrification: progress without noise.

In 2000, Odisha was the poorest state in India. Naveen Patnaik came to power in a state that trailed even Bihar in virtually every development metric, from infant mortality to per capita income. Cyclones routinely killed thousands. By 2024, the state had greatly improved its human development index, slashed infant mortality and elevated per capita income to within 10% of the national average. For many, Cyclone Fani in 2019 showcased Odisha’s new model of governance: 1.2 million were evacuated and thousands rescued.

When the Bharatiya Janata Party swept the state in the 2024 elections, it inherited an emptiness. Development without story leaves a vacuum that ideology is eager to fill. The result has been a compressed collapse in the rapid distillation of what took the Hindi belt a decade: moral reordering, institutional erosion and the replacement of administration by emotion and ideology.

Cuttack’s outbreak of communal violence marked the moment when Odisha’s bureaucratic faith in neutrality met an ideological order which feeds on passion. Under Patnaik, governance promised efficiency, but under Chief Minister Mohan Majhi, it demands emotion. The new dispensation offers deliverance, not development. The rhetoric of belonging has replaced the language of service.

In that conversion, the meaning of citizenship has changed. No longer the bearer of rights, the citizen is now the participant in a civilisational drama. The very instruments that once enabled efficient governance under Patnaik – bureaucratic obedience, centralisation, deference to technocracy – now hasten ideological consolidation. A system designed to manage cyclones efficiently cannot weather communal myths.

Majhi’s own story, as the first tribal chief minister of Odisha from the BJP, was meant to symbolise inclusion. Instead, it aligns with a national pattern where Dalit and Adivasi identities are folded into the Hindutva narrative, their distinctiveness subsumed. Odisha’s Adivasi population, estimated at at least 23%, are facing increasing Sanskritisation.

Historian Biswamoy Pati notes that Sanskritisation involves the Hinduisation of Adivasi deities and rituals. This has been exacerbated since 2024 under the BJP through policies and communal mobilisation in Adivasi areas. In December, for instance, legislators moved private bills in the state assembly proposing a ban on beef and harsher penalties for violations.

In Odisha, what unfolded gradually elsewhere has manifested at warp speed – decades of harmony unravelling in mere months. Each episode – from communal clashes in Balasore in June 2024 to the violent assault on two Dalit men in Ganjam – feels like an aftershock of a deeper quake.

This is vigilantism as governance. Outrage becomes routine and the repetition of violence dulls accountability. Violence is now proof of ideological vitality.

Memory as future

Opposition parties condemn politely, administrators promise peace, but the real deficit is a language of resistance. Against the BJP’s narrative of grievance and pride, Odisha’s older, almost apolitical neutrality offers only reticence. If pluralism is to recover, it must speak again – not in bureaucratic tones but in emotional ones. The defence of harmony must rediscover the music of coexistence that once defined us.

What we have witnessed is the natural process of societal collapse, compressed into months rather than years. Yet compression can work both ways. What collapses quickly can also recover quickly – if it remembers what made it resilient. Because the betrayal – the pratarana – is not what one community has inflicted upon the other. It is between Cuttack and Odisha’s own memory of itself, between what it has been and what it has forgotten how to protect.

In the hauntingly beautiful Odia melody, Hrudayara Ehi Sunyataku – to this emptiness of the heart, the lover speaks to absence, not anger.

In Cuttack today, that absence feels civic, not just romantic: the ache of a city that loved effortlessly, and now deals with its aftermath. We look at each other in shock and sing:

Pratarana kiye kahaku deichhi, pratidhwani kahe, tume! tume! tume!

I do not understand fully, who has betrayed whom I cannot tell; I only hear the echo of a voice, my love, that reminds me of no one but you! you! you!

Sahasranshu Dash is a research associate at the International Centre for Applied Ethics and Public Affairs in Sheffield, the United Kingdom.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting