When Sahaya Teresa’s son, Kevin Santiago, completed his Class 10 studies four years ago, she decided that he needed to change schools.

This was because Santiago aspired to become a doctor and wanted coaching specifically to appear for the intensely competitive National Eligibility Entrance Test for admission to undergraduate medical degree programmes.

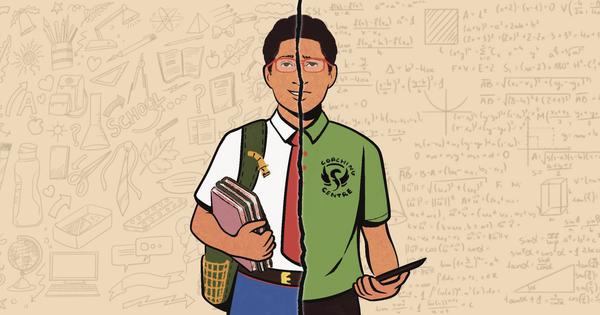

While some students enroll in both regular schools and separate coaching programmes, Teresa worried that such an approach might be too much of a burden on her son. So, she began to look for schools that had arrangements with coaching institutes to offer training for the test along with their regular curriculum.

“I was determined that my son should have a holistic school experience,” she said. “So, I felt that if I admit him to a school that has both regular classes as well as coaching classes, he will not miss out on anything that other students in regular schools experience.”

Teresa enrolled her son in a school that fell under the Central Board for Secondary Education and was also affiliated with one of the most prominent coaching institutes in the country.

But she was in for a shock. The school was nothing like they had expected.

Rather than offer an integrated programme, it separated students into two groups: those who had signed up for the coaching programme and those who had not. The former group attended almost no other classes other than those focused on test training.

This is a common arrangement in schools that also focus on training students for entrance tests. In some other cases, schools offer their own coaching programmes. A third kind are “dummy schools”, where students are allowed to enroll but are not required to attend any classes – instead, their attendance is marked automatically and they focus solely on pursuing coaching programmes. This allows them to take their board exams, even as their main goal remains to clear entrance tests.

In Santiago’s school, classes began at 8 am and continued till 4 pm – each period lasted an hour-and-a-half.

Only for two periods each week, teachers held classes in subjects such as English, psychology and artificial intelligence. The rest of the time was spent in classes conducted by teachers from the coaching institute.

Students received instruction during this time, but if they had any further questions, teachers would not take them up during school hours. Instead, students had to travel afterwards to the institute’s office, where separate hours were allotted for students to clear up their doubts with tutors. For this, they would have to obtain specific permission from the office.

This format effectively negated the main reason Teresa had chosen to send her son to the school. “The very reason I chose this option was I didn’t want my son to have to travel from one place to another and feel hassled,” Teresa said. “And that was exactly what was happening here.”

Santiago also said that because they were not “regular” students at the school, they were not allocated proper classrooms or infrastructure. They were also not included in school events. “Every time there was a holiday or annual days or sports days, we were asked to go to the institute for classes and we were not involved in any activities,” he said.

The calendar was so poorly planned that sometimes, students had to write parallel sets of exams – one conducted by the school and one by the coaching centre.

Further, he recounted that as a result of the mixed model, students received poor treatment from both sets of teachers under whom they studied. “The schoolteachers had a step-motherly attitude towards us because most of our classes were with the institute,” he said.

The teachers from the coaching institute also did not appreciate that on some days they had to travel all the way to the schools for classes. “They had students who were enrolled in dummy schools come directly to the institutes, which they preferred, because they did not have to travel every day to the schools,” he said.

What worried Teresa the most was that the school focused only on training students for the NEET, and not at all for their board exams. “They were not teaching the students the NCERT portions,” she said, referring to the National Council of Educational Research and Training, which sets the curriculum for the education board.

This was a problem, Santiago explained: “If you are unable to crack NEET, you have to rely on your board exams to get into some other course. So it is equally important to focus on both.”

Teresa contended that this lack of focus on students was inherent to the design of these schools. “Coaching is a very commercial endeavour,” she said. “The institute only picks the top ten students and focuses on them. They don’t care for any of the other students.”

This story is part of Common Ground, our in-depth and investigative reporting project. Sign up here to get the stories in your inbox soon after they are published.

Authorities have noted the growth of such models of schooling with concern.

The Central Board for Secondary Education prohibits schools from allowing coaching institutes to function in their premises. “Some schools are organising such programmes by naming it an integrated school programme that teaches both CBSE syllabus and prepares students for various entrance examinations to mislead students and their parents,” the board stated in a 2019 circular.

It added, “No tuition/coaching classes against the spirit enshrined in the bye-laws of the Board shall be allowed in the school that consumes and affects regular time table of the school, deviates the focus of students from regular course of study or promotes any commercial activity.”

In 2024, the board conducted surprise inspections in 27 schools in Rajasthan and Delhi to “ascertain that the schools were operating in compliance with the norms of regular attendance of students in schools”.

Following this, the board withdrew affiliation from 21 schools and downgraded six schools from senior secondary to secondary level – that is, it cancelled their permissions to enroll students in Class 11 and 12. In another inspection conducted in Delhi, Karnataka, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Uttar Pradesh and Ahmedabad, all 29 schools that were inspected were issued show-cause notices.

Earlier this year, the board announced that it might debar students who were not attending regular schools from attending their board exams.

More recently, the problem of such schools in Rajasthan has been in the news – the state is known for its coaching culture, and, concomitantly, a growth in dummy schools. In September, the Rajasthan High Court ordered the state, along with educational boards in it, to establish special investigation teams to conduct surprise inspections on schools and coaching institutes to tackle the rising problem of dummy schools in the state.

But despite these warnings and crackdowns, such schools are flourishing across the country. A casual search online leads to Reddit and Quora threads where parents seek recommendations of “dummy schools” in particular cities to which they can admit their children. Some of these queries receive responses, with commenters providing names of these schools and highlighting their advantages and disadvantages.

Indeed, schools themselves often display their associations with coaching institutes. “Schools openly advertise that they have tie-ups with coaching institutes,” said Prince Gajendra Babu, an education activist from Chennai.

Babu has campaigned for years against coaching institutes – among his main objections is that they charge high fees and thus deepen the divide between students of different backgrounds.

That schools had begun to associate with them was deeply worrying, he noted.

“The increasing prominence of coaching institutes is leading to the dehumanising of education. Children are lonely and are not allowed to have any interest in anything besides studies,” he said.

VP Niranjanaradhya, an activist based in Bengaluru noted, “These schools are doing education a great injustice. They are not looking to expand a child’s knowledge, encourage socialisation or critical thinking, which is the primary purpose of education. They have made education a business.”

Among the most serious problems with such schools is that most offer students a stunted education, students that Scroll spoke to said. They argued that the impacts of this can remain with them for years.

Meera Sanjay, currently enrolled in an undergraduate engineering programme, said that she is still recovering from the damage that her last two years of schooling did to her.

Sanjay, who asked to be identified by a pseudonym, enrolled for her Class 11 and 12 studies in a branch of a prominent group of schools in Bengaluru that offers its own training programmes for entrance tests. She wanted to appear for the Joint Entrance Exams for entry into engineering colleges, and had heard that the group offered strong training.

Upon joining the school, Sanjay and her classmates were divided into batches on the basis of their academic record. The top batch consisted of students who had already been part of the group’s coaching programmes before entering Class 11. “There were students who had previously studied at the same school and so had already completed the syllabus that we were studying,” she said. “Some coaching programmes start from the sixth standard.”

Other students who wanted to join this top batch had to clear an exam first. “If they wanted to join this batch and if they had enough marks, they were added to the batch,” she said. “This batch was mostly preparing for the top engineering colleges in the country, like the IITs.”

These batches also paid higher fees. Santiago noted that in his school, too, students who enrolled in the coaching programme paid higher fees, separately to the institute, rather than to the school.

Sanjay’s school also recommended that the students in the “top” batch take up accommodation on campus, for which there was an additional fee.

“A girl who lived just 3 km away also stayed on campus. This way they could be studying all the time,” Sanjay said. “In fact, it was only three months after I joined the course that I saw someone who belonged to that batch.”

She recounted that a middle batch of students comprised students who were considered less academically accomplished, and so were trained for entrance to a wider pool of colleges. A lower batch comprised students who were mainly prepared for board exams.

Lower batches of students were assigned less qualified and skilled teachers, Sanjay said. She experienced this firsthand because at one point, she moved from a middle batch to a lower batch. “There was a significant difference between the quality of the teachers in the first batch and the second batch,” she said.

Indeed, a former teacher from a coaching institute, who asked to remain anonymous, noted that the quality of teachers in such schools was a serious concern. “The sole focus of these teachers is to teach problem-solving,” he said. “There is no effort to make students understand concepts, which is what will help them understand the subject in its entirety.”

He added, “Merely learning problem-solving is not going to help them in their degrees, they need to have a holistic understanding of the subject. Formulating a problem is more important than its solutions.”

Sanjay made the shift to a lower batch, which only focused on the board exams, because the stress of the former was overwhelming her. “I used to do very well until I was in the tenth standard, then I came here and there was so much negativity that I felt discouraged and lost interest in studying,” she said.

Among the most stressful aspects of higher batches were tests that the school held twice a week, after which it would publicly paste a rank-list of students. “This affected everybody negatively,” she said.

Like in Santiago’s school, Sanjay’s primarily trained students only in the subjects they would take entrance exams in – apart from these, they only had English and Kannada classes twice a week each.

In other ways, too, she found her school life difficult and unrewarding, even after she shifted to the lower batch.

The school did not have any extracurricular activities. “One day in the year, we had ethnic day. We were allowed to get dressed up. We paid Rs 500 and were taken to a hall,” she said. “Each class put up a dance performance. And then we were all allowed to dance for about 15 minutes.”

The school also did not have a library or any sports facilities or activities. Sanjay and her friends would play some sports on their own on the ground during the lunch break or after school. “Our classes got over at 5.30 pm, so we could play, others finished at 7 pm, so they didn’t,” she said.

Most students, in fact, did not find time for any other activities. “Most students would not attend any college fests outside or any other extracurricular activity, because they would have to miss classes or study time,” she said.

Sanjay herself suffered from the absence of these activities. “I forgot how to draw, which I did very often before I joined the school,” she said. “I used to play a lot of sports too, and once you lose these habits, it’s difficult to go back to them.”

VP Niranjanaradhya explained that this was not an uncommon phenomenon in such schools. “Since there is such a focus on students writing competitive exams, teachers seem to have washed their hands of ordinary students who have other interests,” he said.

Babu noted that in fact, many parents prefer that students not be “distracted” by subjects that are not essential for exams, as well as other school activities. However, they still want their wards to be enrolled in well-known schools. “It is a prestige issue. They want their students to still be in big schools,” Babu said.

The lack of exposure to non-academic activities also affected Sanjay’s social skills. “I had even forgotten how to talk to people,” she said. “When I came to college and saw all these activity clubs, I found it so hard to participate and to socialise. It was all very overwhelming.”

The two years in the school took a toll on her mental health, and her physical health, she recounted. It took a long time for me to recover,” she said. She added that her classmates also faced adverse health consequences from the stress.

Santiago, too, recounted that the school he attended harmed his mental health. “The experience definitely took a mental toll on me,” he said.

He said that as a result of the stress he faced, he began to lose interest in preparing for the NEET. “It began to feel impossible, I was unable to cope with the competition,” he said.

Teresa did not want her son to continue to suffer this way and decided to shift him to a regular school in the middle of the year. “I knew it was a risk and that it could mess with his preparations, but we decided it was best for him to move,” she said. “He went to a regular school and attended coaching classes outside of school hours.”

After this, Santiago cleared the NEET and is currently in his first year of medical college.

Ahalya S, who is now 20 years old and studying engineering, echoed Santiago and Sanjay’s experiences of finding that their schools tended to focus primarily on high-performing students. Like Sanjay, she also attended a branch of a prominent group of schools, in Bengaluru.

“The teachers were biased towards the students who studied well and the rest of us were sidelined often,” said Ahalya, who asked to be identified by a pseudonym. She recounted, for instance, that teachers would not even make sure that everyone in the class understood what was being taught. “They would just move on with the syllabus if the top rankers said that they had understood,” she said.

She added, “I was made to feel like it was my fault that I was unable to keep up with the speed at which they were teaching. But there was really nothing I could do.”

In fact, teachers frequently put down students who could not keep up. “The teachers would say to our faces that if we don’t pass the exams, we would be spoiling our lives,” she said. “All the teachers had the same mindset. We were meant to feel like we simply did not stand a chance in the world if we didn’t make it.”

She added, “Except maybe the first seven or eight ranks, everyone else in my class was miserable.”

The pressure on students was intense. The school held a three-hour mock test on Sundays and, like in Sanjay’s school, publicly pasted a rank list after the tests. This left students who did not perform well humiliated and embarrassed.

Such practices had the effect of souring the atmosphere in the school. “No one wanted to help each other. If someone forgot their textbook, nobody would share their books with them,” she said. “It was different in my previous school. We would all help each other out.”

The only friends she had in the school were two friends who were from her previous school. “The three of us continued to be friends. We could not make friends with anybody else,” she said. “The other students hated even discussing studies or anything else. This kind of individualistic attitude was everywhere.”

Like Sanjay, Ahalya also found that her mental health suffered, to the extent that she sought professional help. “I was diagnosed with depression,” Ahalya said.

As a result, she was forced to take a gap year after her Class 12 studies so that she could focus on recovery.

She was also so disheartened by her experience at the school that she gave up on cracking the NEET after one unsuccessful attempt – though often students clear it only on their second or third attempt. “I just could not imagine going through all that again so I gave up on NEET entirely,” she said. “I did not want to be traumatised again.”

The former coaching institute teacher said that the current system failed to account for the academic paths of those students who did not clear the exams they studied for. “A large majority of the students don’t get in because the competition is so intense,” he said. “These children need to find other options. And if their fundamentals are not strong, if they have not been given holistic education, not taught how to investigate, how to conduct experiments, they are going to suffer in the future.”

Like Sanjay, Ahalya said that she still battled with a lot of the problems that had resulted from her time at the school. “I have an intense fear of giving exams,” she said. “I’ve become an extremely anxious person, and because we had to shut down for those two years, I struggle to socialise.”

In all the three schools, the students said that they did not have a dedicated counsellor that they could approach – though Santiago recounted that his psychology teacher also served as the school counsellor. Thus, students were largely left to navigate any mental health problems they faced on their own.

Activists said that it would not be sufficient for the CBSE to only crack down on schools that violated regulations. The root of the problem, they noted, was the entrance exam system itself. “There are only so many seats and the people vying for them are so many,” Ahalya said.

Babu argued that the rise in the phenomenon of dummy schools was directly linked to the government’s promotion of entrance exams for nearly every course of study today. “The increasing focus on entrance exams has led to students being viewed as consumers and education as a commodity,” he said.

He argued that rather than force students to write numerous intensely competitive exams, a better system would entail evaluating them on the basis of their board exam marks. “Students are properly evaluated by their respective teachers through the board exams,” he said. For undergraduate courses, he argued, “It is only just and fair to consider their board exam scores for admission.”

He added, “This is not an equal playing field. Only those who can afford this kind of coaching crack the exams. How is this fair?”

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting