In 1954, Justice Vivian Bose of the Supreme Court proclaimed that the Indian Constitution had “blotted out, in one magnificent sweep, all vestiges of despotic power in India; that the colonial past was obliterated and a new order born”. This is a half-truth.

The enactment of India’s Constitution marked the demise of imperialism and the dawn of democratic republicanism. But it failed to embrace the philosophy of Mohandas Gandhi who symbolically continues to lead the long and unfinished march to India’s redemption, carrying the torch of ahimsa and swaraj – the refusal to harm and the sovereignty of the self.

Gandhi’s philosophy is especially urgent in light of Congress veteran C Rajagopalachari’s prophetic warning in 1922, written from a prison cell: “Swaraj will not at once, or even for a time to come, bring better government or greater happiness for the people. Elections and their corruption, injustice, and the tyranny of wealth, and insufficiency of administration, will make a hell of life as soon as freedom is given to us.”

Rajagopalachari’s pessimism appears to have prevailed over the optimism of Jawaharlal Nehru’s “tryst with destiny” as India’s institutions failed to guarantee justice and dignity for all.

More than 23 years ago, the Indian government’s Report of the National Commission to Review the Working of the Constitution in 2002 captured this malaise: “There is pervasive disenchantment with the working of the institutions of democracy. People themselves seem almost to have resigned to what they consider their inevitable fate […] yielding place to a sense of revulsion against the State and a deep distrust against the machinery of government.”

This Gandhi Jayanti, Gandhi’s ideals of swaraj and ahimsa and his emphasis on the moral duties of Indian citizens are worth revisiting. His legacy can offer guidance and solace for the Indian republic and breathe new life into its Constitution.

The village is the individual

Gandhi insisted that the village should be the primary unit of political and economic life, with industries dispersed rather than concentrated. For Gandhi, swaraj was the nucleus of independent India, with the autonomous village republic at its heart.

Gandhi’s concepts of individual swaraj and village swaraj are not contradictory but complementary: self-disciplined individuals form the moral basis for democratic village republics, which in turn provide the social and economic setting for individuals to flourish.

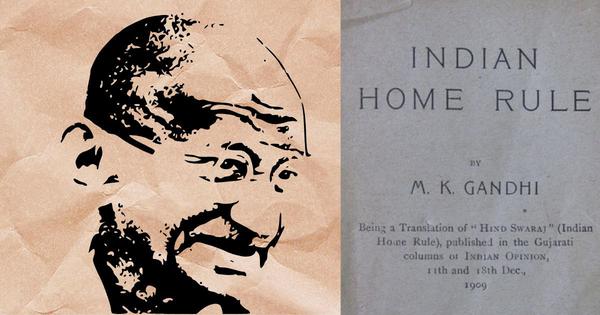

But the founders of independent India envisioned modernity as the primacy of the individual. Gandhi’s vision, which can be traced back to his book Hind Swaraj (1909), clashed with Nehru’s preference for parliamentary democracy and industrial modernity.

Writing to Gandhi on January 11, 1928, Nehru said he did not agree with Gandhi’s views that “India had nothing to learn from the West and that she has reached a pinnacle of wisdom in the past”. “I neither think that the so-called Ramarajya was very good in the past nor do I want it back. I think the western – or rather industrial – civilisation is bound to conquer India, though with many changes and adaptations,” wrote Nehru.

Gandhi and Nehru did agree on fundamental rights and economic advancement. But when the Congress Working Committee finalised a constitutional blueprint in September 1945, another round of debate followed. Nehru said the village was intellectually and culturally backward and that “narrow-minded people are much more likely to be untruthful and violent”.

Similarly, BR Ambedkar, chairperson of the Drafting Committee of the Indian Constitution, rejected Gandhi’s village-centric model: “What is a village but a sink of localism, a den of ignorance, narrow-mindedness and communalism? I am glad that the Draft Constitution has discarded the village and adopted the individual as its unit.”

In 1946, Shriman Narayan Agrawal published The Gandhian Constitution of Free India, a 60-page treatise endorsed by Gandhi. It combined rights with duties, vested sweeping powers in village panchayats and even included an ironic “right to bear arms”. Agrawal compared the Gandhian village to the Greek city-state: small, cohesive, participatory and ethically grounded. Gandhi, endorsing the work, admitted that it reflected his essential ideas.

An expert committee appointed on July 8, 1946, ultimately endorsed Nehru’s vision. Gandhi, disheartened, withdrew from constitutional debates. On April 1, 1947, at a prayer meeting, he lamented: “Nothing will happen on my words. My command will not run henceforth […] But now, nobody listens to me.” However, Gandhi was not rigid about his constitutional vision. Amid Partition and the communal conflagration that ensued, Gandhi endorsed parliamentary democracy with a strong central government.

But decades on, Gandhian village republics are of philosophical and practical relevance for India.

Renewal, individual swaraj

In Gandhi’s imagination, the spiritually empowered individual was the fulcrum of society and the state. Scholar Ananya Vajpeyi, in Righteous Republic: The Political Foundations of Modern India, notes that swaraj and ahimsa were central to Gandhi’s political vocabulary. Only a morally enlightened citizenry, India’s “collective self”, can save the Republic from corruption and violence.

Arghya Sengupta, in The Colonial Constitution: An Origin Story (2023), also points out Gandhi’s emphasis on moral values. He observes that Gandhi saw himself as the “moral compass, guiding the nation in a journey to discover the values that would nourish it and gave it strength”.

“The constitution would take effect later, once the nation became ‘conscious of its own strength’,” writes Sengupta. He says that Gandhi expresses these ideals clearly in The Constructive Programme, a book written in 1941, which “was a categorical affirmation of the significance of morality in building independent India”.

Gandhi envisaged a republic founded on the moral ideals of truth and non-violence rather than on power and coercion. In what became his last will and testament, Gandhi writes of a Lok Sevak Sangh to carry forward the ideals of ahimsa and swaraj.

He also proposed that the Indian National Congress transform itself into this Sangh, dedicated to building a non-violent society through grassroots self-rule. His design of panchayats, structured in ascending tiers of self-governance, reveals his unwavering commitment to decentralisation and power in the hands of people.

Gandhi’s ideas had found real expression when the princely state of Aundh, under Raja Bhawanrao Shriniwasrao Pant Pratinidhi and guided by Maurice Frydman, adopted a “Swaraj Constitution” in 1939. It created a three-tier system of self-governance, with empowered panchayats and a literacy-driven electorate.

Days before he was assassinated, Gandhi thought of constructive workers as vigilant guides to keep Parliament in check. Ultimately, Gandhi’s faith lay in the ordinary citizen – imbued with the ideals of ahimsa and swaraj – to act as a transformative force.

Democracy in India will not be saved by its democratic institutions alone but by the moral courage of its citizens. Rabindranath Tagore’s legendary Ekla Chalo Re, also Gandhi’s favourite poem, captures this ethos:

“If no one answers your call, walk alone…

When dark clouds cover the sky and truth is shrouded,

Be the flame that burns, even if you must burn alone.”

Faisal CK is Deputy Law Secretary to the Government of Kerala and author of The Supreme Codex: A Citizen’s Anxieties and Aspirations on the Indian Constitution. Views are personal.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting