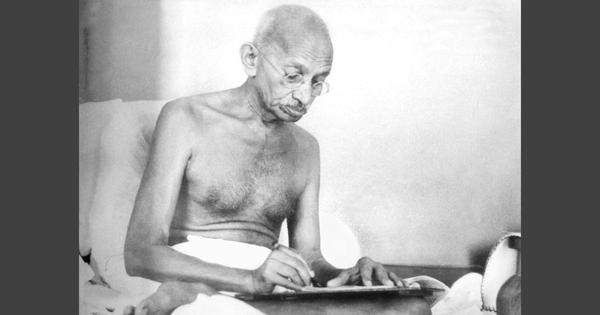

Popular discourse around Mohandas Gandhi has projected him as an eccentric saint by obscuring his overwhelmingly modern and practical side. Gandhi was fastidious about three practices: punctuality, account keeping and documentation. Of the three, the last is perhaps his least known practice. The emphasis on documents not only helped to create a rich archival corpus, but also introduced Indian freedom fighters to a new model of leadership in the early part of the 20th century.

One important aspect of Gandhi’s emphasis on meticulous documentation was the collection of facts and the writing of reports. These two exercises were always central to the colonial state. But over a period of time, under Gandhi’s tutelage, this skill was mastered and instrumentalised by young leaders in the thick of the freedom struggle.

In the 20th century, fact collection and report writing by Gandhian freedom fighters became an effective tool to force the colonial power to respond to natural or manmade disasters. Report writing was an activity that served as an intellectual launchpad for protest movements within the larger freedom struggle. It also helped to raise funds from the public and newly formed civil society organisations in the subcontinent.

One of Gandhi’s major early political successes, the Champaran Satyagraha, was executed on the basis of a massive fact collection and report writing exercise. In 1917, it was the patient collection of statements and facts from Champaran farmers suffering under forced indigo cultivation that led to the abolition of the Teenkathia System.

However, it would be a grave error to assume that the Gandhian approach to fact collection resembled any other dull and unsentimental bureaucratic activity. Here, too, Gandhi was both intuitive and creative. In The Story of my Experiments with Truth, Gandhi gives a detailed account of the fact collection and report writing activity in Champaran preceding the Satyagraha.

Many of the farmers offered repetitive statements to the volunteers recording their testimonies; interviewing thousands of farmers was obviously an arduous task for six or seven volunteers. However, Gandhi appreciated that recounting one’s experience was a cathartic exercise for many farmers. To Gandhi, this mattered more than whether the experiences of the witnesses were essentially similar.

The farmers in Champaran were also subjected to a test before their statements were recorded. Gandhi insisted on this despite the extra time and labour involved. He wished to make sure that the report spoke truth to power. When a CID officer was deployed to keep an eye on the exercise, Gandhi and the volunteers treated him with courtesy and voluntarily shared as much information as possible. Gandhi wrote that the presence of the officer had two salutary outcomes. Peasants lost some of their fear of officers; their presence nevertheless “exercised a natural restraint on exaggeration”.

As always, Gandhi was accommodative of people who had turned up just for his darshan, thereby ensuring that this monumental exercise was not severed from ordinary human interactions. Gandhi took out time and allowed himself to be “exhibited”. And finally, never one to be carried away by notions of moral superiority, Gandhi also made it a point of writing letters to and meeting plantation owners in Champaran to ascertain their point of view.

Gandhi’s unwavering focus on documentation made him one of the rare world leaders, who, despite not being in any consequential position in government or commerce, always had by his side a secretary. The secretary tracked, arranged and preserved his correspondence, articles and other forms of documentation associated with each and every activity. People who served Gandhi as secretaries at various stages of his life – Mahadev Desai, Pyarelal Nayyar, V Kalyanam and NK Bose – went on to become respected figures in their own right.

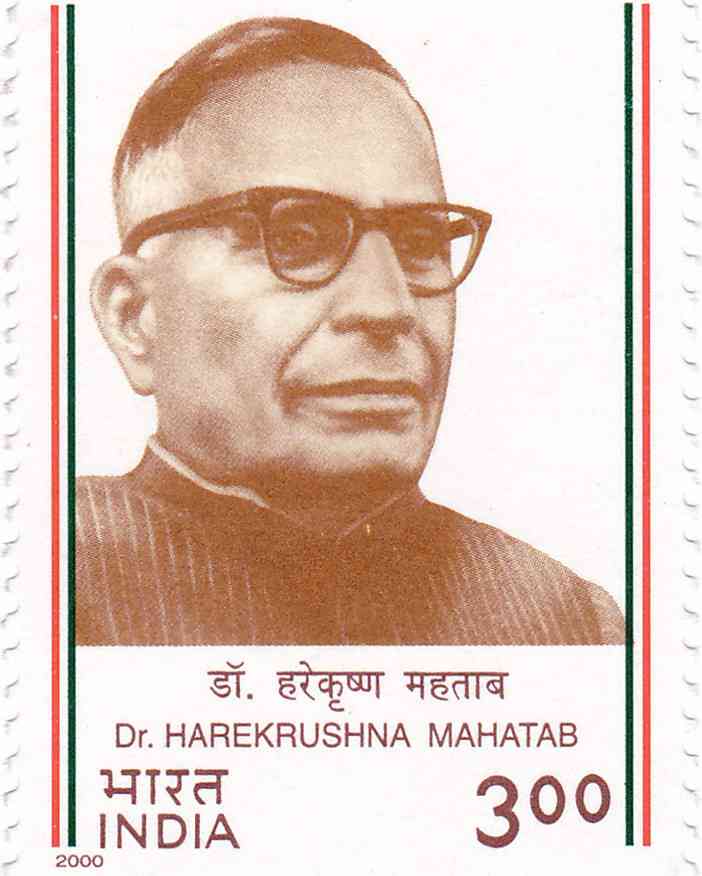

The success of the Champaran experiment influenced non-violent freedom fighters of the next generation. Almost a decade later, major floods devastated Balasore district of what was then called the Bihar and Orissa Province. A report prepared by the colonial government played down the immense loss to life and property. However, former Orissa Chief Minister Harekrushna Mahtab, then a young Congressman, along with volunteers Bhairaba, Abhiram Nanda, and Upendra Nath Panda, set out to collect facts and write a report. In his iconic memoir, Sadhana Ra Pathey, Mahtab has described how this group of fact finders went about their task despite undergoing physical and emotional distress.

The volunteers could not find potable water in the flood ravaged areas and had to drink from water sources in which dead cattle and goats were floating. Mahtab described how the four friends tried to rebuild a few collapsed huts and removed rotting carcasses in flood-stricken villages. The task of fact-finding and report writing did not exclude volunteering for strangers at the cost of one’s comfort, health and social status. Such interventions also assume great significance in a caste-ridden society.

Visiting India in 1927, the ornithologist and travel writer HG Alexander noted that Gujarat, which was also simultaneously devastated by floods, received Rs 2.16 crore raised for relief and rehabilitation. Meanwhile, only Rs 9 lakh could be collected for Orissa. Alexander cited the indifference of the press in Calcutta towards the Balasore floods, while conscientious reporting by the Bombay press on Gujarat floods made a major impact on public consciousness.

In this context, the report writing by Mahtab and his friends secured victories in terms of material support and political impact. Organisations such as the Agarwal Panchayat, Marwari Relief Society, Gujarati Relief Party, Ramakrishna Mission, and Bharat Sevashram rushed to these areas with resources and volunteers. But for these organisations, even Rs 9 lakh could not have been raised.

Meanwhile, the report prepared by Mahtab and his friends left the government red faced with embarrassment. After denials and refusals, the British Collector of Balasore had to accept the validity of a report filed by four ordinary citizens.

The episode in Balasore is just one example of a practice that was followed by Gandhi and Gandhian leaders all their lives. No activity, visit, or event in which Gandhi played a key role was ever considered too insignificant for documentation. For instance, in 1938, Gandhi visited Delang, an outback in Orissa that was then one of the most remote provinces in the subcontinent. A detailed report on the event was recorded and published in Hindi from Wardha in the same year.

Gandhi’s emphasis on fact collection and report writing, outside the purview of the state, was followed by Gandhians right up to Independence. In his memoirs Smruti O Anubhuti, the former chief minister of Orissa Nilamani Routray has written how he and fellow political activists, Hrudananda Mallick, Abhay Charan Nayak, Akuli Mishra, Ramachandra Patnaik, banded together to form a fact-finding Riot Distressed Odia Enquiry Committee in the wake of the 1946 riots in Calcutta.

After the riots, many provincial governments in the subcontinent had sent their representatives to present facts before the Spens Inquiry Commission. Though the Odia community in Calcutta had sustained considerable losses, its provincial government had not drawn up a list of official representatives.

However, after painstaking efforts, these young Gandhians managed to submit a memorandum to the Bengal Government listing the number of dead and injured as well as details on losses to property. The report was accepted and many affected Odias received help from the government.

The Gandhian method of visiting a poor, oppressed, or calamity ravaged spot, collecting facts by interviewing ordinary and often unlettered people, and preparing a report that challenged or prodded the colonial state was a unique leadership model. In Mahtab’s words, a non-violent movement requires more research and planning than a violent, armed campaign.

Sampad Patnaik and Jatindra Kumar Nayak are researchers based in Odisha.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting