The G5A cultural centre in Mumbai has organised an Anand Patwardhan retrospective between October 2 and 5. The programme – featuring 10 out of his 13 documentaries and two short films – covers the breadth of the 75-year-old filmmaker’s thematic concerns over five decades, including human rights, majoritarianism, hyper-nationalism, casteism, ecological damage and protest movements.

Patwardhan hasn’t just consistently held a mirror to injustice, but also explored its possible roots as well as the ways in which it can be countered. He has frequently faced censorship, fighting battles in the courts and beyond to ensure that his films can be seen by the public.

Patwardhan’s first-full length documentary was Waves of Revolution (1974), about the Bihar Movement steered by Jayaprakash Narayan against Indira Gandhi’s repressive regime. He has borne witness to a country betrayed by its leaders but redeemed by morally upright citizens who abide by a historical commitment to non-violence and a Constitution that protects all Indians regardless of their beliefs.

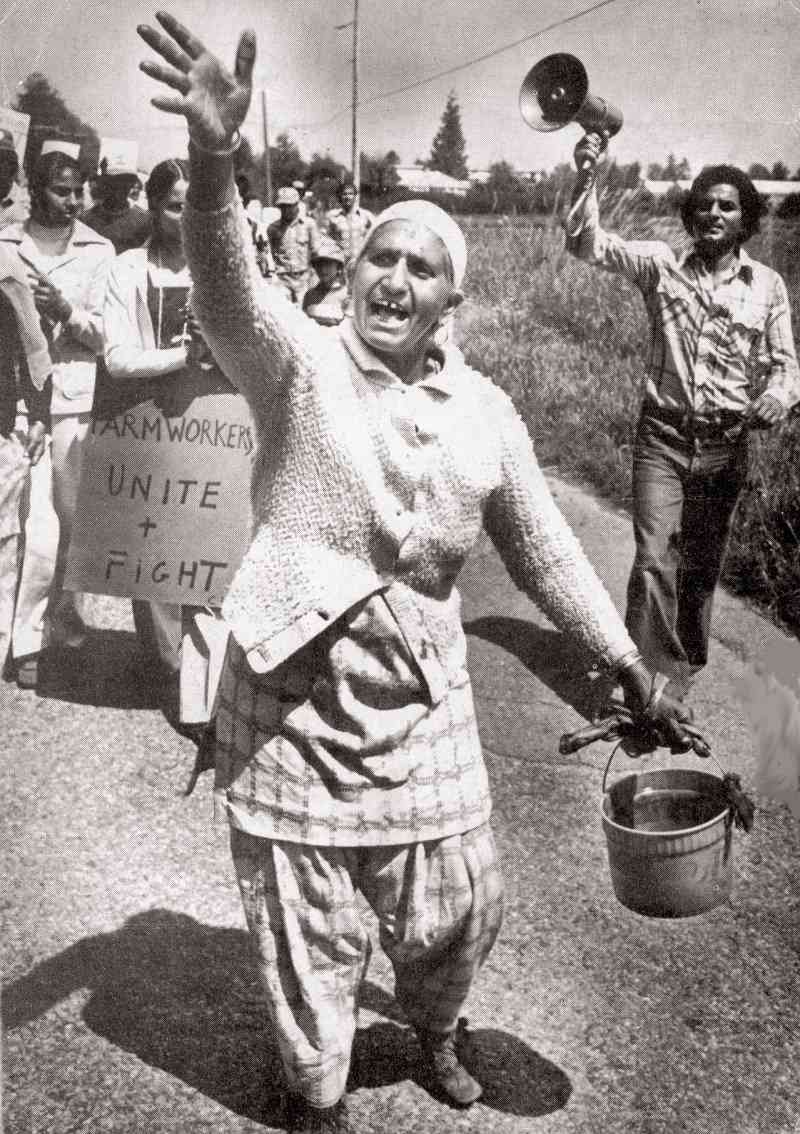

The G5A programme includes Prisoners of Conscience (1978), about activists who were arrested at the time of the Emergency in 1975 and remained behind bars after the Emergency ended in 1977. A Time To Rise (1981), made with Jim Monro, follows Punjabi farm labourers in Canada forming a union against exploitative working conditions.

Bombay: Our City (1985) squarely examines the city’s heartless policy of eviction and demolition towards its poor and working-class people. A Narmada Diary, co-directed with Simantini Dhuru, looks at the Narmada Bachao Andolan’s non-violent struggle against the Sardar Sarovar Dam. In War and Peace (2002), Patwardhan critiques the nuclear policies of India and Pakistan, while also highlighting peace efforts on both sides of the border.

Three of Patwardhan’s seminal documentaries on religious fundamentalism are part of the retrospective.

In Memory of Friends (1990) sets the legacy of the revolutionary Bhagat Singh against the Khalistan movement in Punjab.

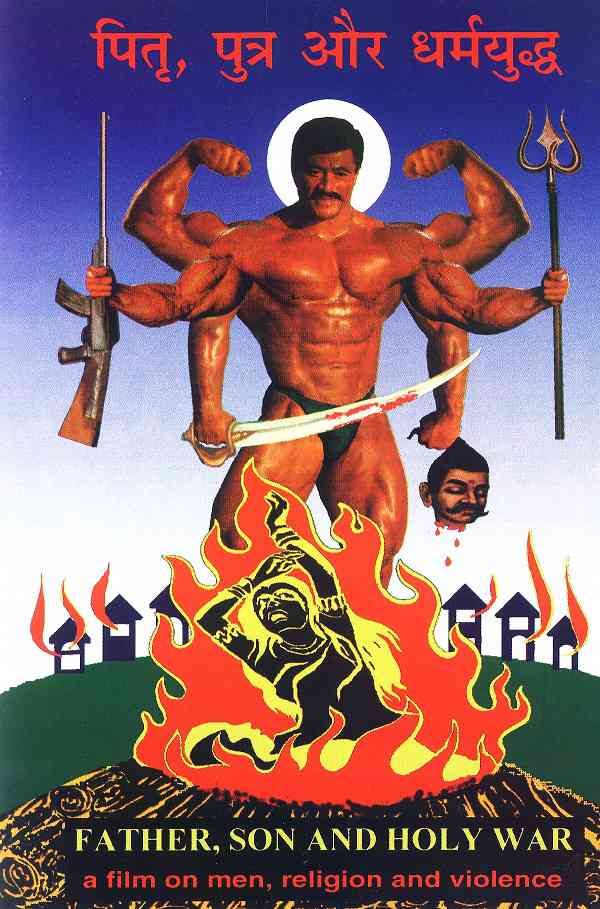

Father, Son and Holy War (1995) is a multi-layered examination of the intersection of Hindu nationalism, anxieties over masculinity, and the use of misogynistic rhetoric by Hindu and Muslim leaders to justify violence. Reason (2018) lays bare the ways in which the Hindutva ideology targets dissenters, activists and minority groups.

Reason investigates the assassinations of the rationalist Narendra Dabholkar, the Communist leader Govind Pansare and the journalist Gauri Lankesh. There are also sections on the fanning of obscurantist beliefs by Hindutva groups and vigilante attacks on Muslims and Dalits under the guise of cow protection.

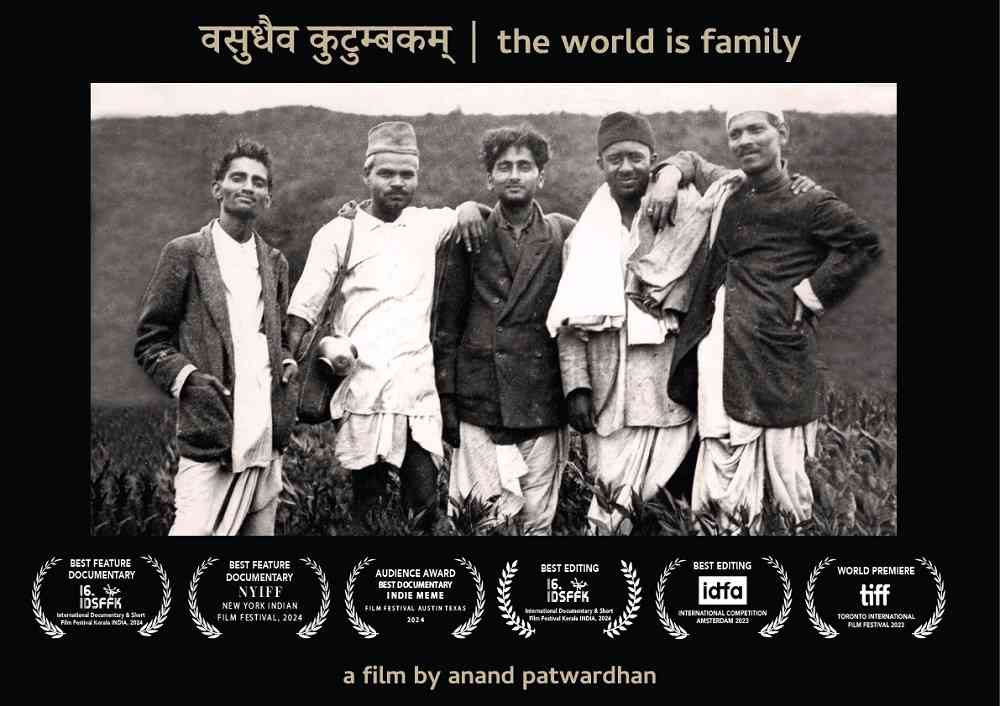

Jai Bhim Comrade (2011) is an exhaustive study of the politics surrounding Dalit identity, Dalit activism and the backlash by upper-caste groups. Patwardhan’s most recent film The World is Family (Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam, 2023) looks back on his personal journey, whose building blocks include the progressive, socialist values espoused by his parents and extended family.

Born and raised in Mumbai, Patwardhan was, by his own admission, an “amiable member of the dilettante elite”, floating through college here before being catalysed by his time at Brandeis University in the US.

While he calls himself an “accidental” filmmaker, his chosen mode of expression against inequity – the documentary – has arguably conscientised and inspired several generations.

Patwardhan spoke at length to Scroll about his formative years, his runs-in with censorship and his commitment to speaking truth to power. Here are edited excerpts from the interview.

What role did cinema play in shaping your worldview during your formative years?

I have said this before – I didn’t like movies at all. When I was very young, I thought people actually died for real in films and would get upset.

Sometime in the 1960s, my father worked with his father-in-law, one of whose businesses was exporting B-movies to the Middle East, films like Tarzan Meets Captain Kishore, Lady Robinhood and films starring Nadia. Some of these are now cult classics.

My parents were also members of film societies like Anandam, so I watched films there. But I had no real inclination towards cinema.

I went to Elphinstone College, which was not yet highly political. I enrolled in English Literature. I loved literature until I had to study it – we were reading texts like Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene, to which I felt no connection.

My classmates included Homi K Bhabha and Akeel Bilgrami, who were brilliant, while I was uninterested in my studies. Despite middling marks, I got a scholarship to Brandeis University in Massachusetts – having cheekily argued that my brains were inversely proportionate to my marks.

What was Brandeis like? And how did it change you?

At Brandeis, I changed my subject from literature to sociology. The Viet Nam war was at its peak and so was the students’ anti-war movement. Brandeis became the East Coast co-ordinating centre. I was quickly drawn into the movement.

Even though my family had been deeply involved with India’s freedom struggle, they had never overtly imposed their thinking on me. I was an amiable member of the dilettante elite, a perfectly happy-go-lucky parasite. It was anti-war protests at Brandeis combined with what I had begun to read, from Gandhi and George Jackson to Frantz Fanon, that switched my thinking.

I was arrested twice, once for protesting against Raytheon, an anti-personnel cluster-bomb factory, and once when Viet Nam veterans threw their war medals at the Pentagon.

Were you involved with filmmaking at Brandeis?

In a rudimentary sense, when I borrowed a camera from the Theatre Arts Department to film anti-war protests. I also made a short film to raise funds for refugees who were pouring into India from East Pakistan. This was before the birth of Bangladesh. I watched films about the civil rights movement and Latin American liberation cinema.

I began working with the United Farmworkers Union, largely Mexican immigrant workers led by Caesar Chavez. The union led a grape boycott and a lettuce boycott to put pressure on growers to sign contracts. Across America, support committees like ours helped with the boycott, going to supermarkets and picketing.

After my studies were done, I hitchhiked to California to work fulltime with the UFW on $5 a week and food stamps for rations. At one point, Chavez endorsed the Democrat George McGovern against the Republican Richard Nixon. We would go door-to-door telling people about the wiretapping incident at Watergate. It wasn’t big news yet, so nobody believed us and Nixon won by a landslide.

After Brandeis, you returned to India – and ended up making Waves of Revolution.

I came back in 1972. I worked in a village project, Kishore Bharati, in Madhya Pradesh’s Hoshangabad district. It was started by Dr Anil Sadgopal, a scientist and idealist who had come back from America. I spent two years there, farming and teaching. While I was there, I made a film strip to motivate rural tuberculosis patients to continue their treatment.

In 1974, I moved to Bihar to witness a mass movement led by Jayaprakash Narayan. As police violence was expected, I was asked to take photographs during a big rally in Patna. Instead, I went to Delhi and came back with a friend, Rajiv Jain, who had an 8mm camera and a Super 8 camera.

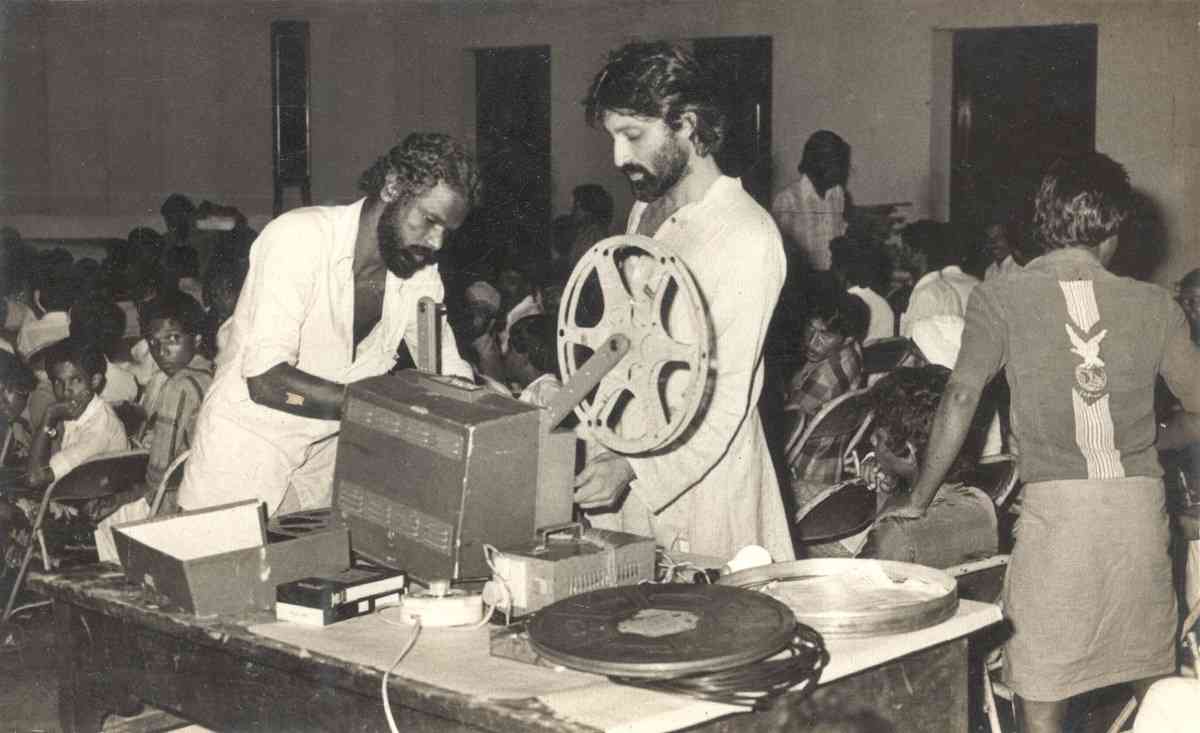

It was reversal stock, not a negative. So every time you screen a film, you scratch or even tear the original. We projected the 8mm footage and filmed that with a 16mm camera to enlarge the image.

Later, I went back to Bihar with Pradip Krishen, who had just bought an old Bell and Howell hand-cranked camera. The 16mm we used was actually outdated colour stock left over from a film Shyam Benegal was making. Outdated colour stock could still yield an image when processed as black and white. All this eventually became Waves of Revolution.

Did you manage to show Waves of Revolution in India?

Soon after the film was completed in 1975, the Emergency was declared. All the people we had been working with were jailed. I went underground.

Jahnu Barua had the film smuggled out of the laboratory where it was being processed without anyone knowing what the film was about. We managed to show the film clandestinely a few times. Mani Kaul helped me to project it. The film was finally cut into four smaller pieces and smuggled out with whoever was leaving the country.

In September 1975, I got admission and a teaching fellowship for a Masters in communications at McGill University in Canada. I collected and put together the film and started showing it across North America. After the Emergency ended in 1977, I came back to India and started showing Waves of Revolution. It was celebrated in the press, but we had to fight to show it on Doordarshan.

I had added an epilogue, saying that the Janata rule being talked about in the film was about grassroots democracy and not the Janata Party-led coalition that replaced the Congress party. LK Advani was now the Information and Broadcasting Minister as the coalition had the RSS in it.

Doordarshan at first refused to telecast the film with the epilogue. We used public pressure to get the film with its epilogue shown at four Doordarshan centres in the country.

Waves of Revolution was followed by Prisoners of Conscience and A Time To Rise – and these documentaries similarly ran into trouble.

After the Emergency ended, I found that many political prisoners had still not been released. So I made Prisoners of Conscience in 1978. The film included an interview with Jayaprakash Narayan speaking for the release of all, including Naxalites, Nagas and Mizos.

The footage of prison interiors was thanks to Pooh Sayani, who was making her fictional children’s film Hungama Bombay Ishtyle. She had got access to prisons. I pretended to be her second unit cameraman. I filmed the outsides of several prisons and evoked some prison scenes through paintings.

The censor board denied Prisoners of Conscience a certificate until Satyajit Ray watched the film and wrote a letter asking how it could be denied a certificate even though the Emergency had ended.

After Prisoners of Conscience, I went back to Canada to complete my masters. I met farm workers of Punjabi origin organising in Western Canada. They had watched Prisoners of Conscience and wanted me to make a film on their struggle. So I got together with the Canadian filmmaker Jim Monro and we made A Time To Rise in 1981.

The National Film Board of Canada helped in the completion of A Time To Rise. The funny thing was that on returning to India in 1982, the film was denied a censor certificate because the censor board said it would offend Canadians. We won a certificate after I pointed out that the NFB had bought distribution rights in Canada.

You moved back to Mumbai in the early 1980s. What did you make of the city?

When I came back in 1982, Bombay had changed. Or maybe I had changed. I started seeing things I hadn’t seen or registered before.

People’s homes in Bombay were being demolished. It was a shock to see homeless people right outside my own footpath.

The People’s Union for Civil Liberties and Lawyers Collective had filed a court case demanding that the right to shelter flowed from the right to life guaranteed by India’s Constitution. I started taking photographs to help the case of the homeless. I had bought a second-hand camera when I was abroad. I started filming, and that became Bombay: Our City.

In those years, we could mobilise protests on a huge scale, which you cannot today. The film was shown widely across the slums of Bombay. I had two 16mm projectors. Apart from our team, Meher Pestonji, now a well-known poet, tirelessly showed the film on makeshift screens across the shanty towns of Bombay.

In the 1990s, you began documenting the rise of majoritarianism, starting with In Memory of Friends. How did this shift happen?

Until the mid-1980s, majoritarianism had not become the dominant force it is today. My films up to then were talking about working class issues, not religion per se. I was thinking in terms of class and fighting for justice for workers and the homeless.

By the 1990s, things started to change. That is when I made what later became a trilogy, although it didn’t start out that way – In Memory of Friends, about Bhagat Singh and the Khalistan movement in Punjab, then Ram Ke Naam, about the Ayodhya temple, and Father, Son and Holy War, which was about both Hindu and Muslim fundamentalism through the prism of gender and masculinity.

These films faced censorship too – but you fought your way through the courts to get them shown on the national broadcaster Doordarshan.

Bombay: Our City was the first time I went to court. The film went through the censor board without cuts, after an appeal. It won a National Film Award for best documentary, which a slum dweller went on to receive on my behalf.

My lawyer and friend PA Sebastian said, if you have won a national award, the film should be shown on Doordarshan. But Doordarshan said the film was ‘not fit for telecast’.

We took them to court and won after a few years. The film was shown without any announcement on Doordarshan, at 11 pm. After In Memory of Friends won a National Film Award, the same thing happened.

After we won our third court case for Ram Ke Naam, the judge ordered the film to be shown at prime time. In those days, multiple private channels were yet to spread. Doordarshan was what everybody watched. So millions watched the film at 9 pm, right after the news.

Father, Son and Holy War went to court thrice. We won in the high court, the government appealed in the Supreme Court, the Supreme Court sent it back to the high court. We won again and they appealed again. This time the Supreme Court ordered its telecast. The film was finally shown in 2005, 10 years after it was made.

You have often called yourself an “accidental” filmmaker.

Yes, I have always said that. Everything falls into place almost by chance. Dedication is not a term I’d use.

I just did what I enjoyed. I was getting enough feedback to continue. Eventually, documentary filmmaking became my identity. I never thought of making fiction, and also never made an ad film.

How would you describe your approach to documentary filmmaking?

One could say that my films have been driven by their subject matter rather than me driving the film.

I don’t want to be the creator of the moment. I want to be the recorder of the moment. It’s a combination – you record the moment and then you juxtapose it with other moments and make a narrative out of it. You are creating in a sense, but not creating what is in front of the camera.

I never work with a script. When I have shot something, I look at it to see where it’s leading and then shoot some more that expands or takes off from what I have already shot. That keeps adding up.

Every film is challenging until you get there. Finishing a film is also arbitrary because real life never ends. That’s why many of my films have epilogues, because I finish the film and then something more happens.

Like I finished Ram Ke Naam and then the Babri mosque got demolished and later my main protagonist, the priest Lal Das, was killed. They became a part of the epilogue added almost two years after the main film was done.

You have also been called a “barefoot” documentary filmmaker.

In the early years and even recently, I was sometimes criticised for being ‘political’. My work is called ‘not really art’, ‘propaganda’, or ‘agitprop’ – there are many pejorative labels that attempt to create a hierarchy between high’ art and ‘low’ politics.

It perplexes me, as I don’t see how you can take the art out of politics or the politics out of art. For me, the word art is highly subjective. Anything you put a frame around can become art. I also believe that you can’t set out to make art. It happens by accident. When you consciously try to create art, you only become a con artist.

At some point, I came across Julio Garcia Espinosa’s For An Imperfect Cinema, which reaffirmed everything I had been doing already. The practice of imperfect cinema grew organically.

You want to make a perfect shot but don’t have the means to do so. That doesn’t mean you don’t take the shot. The zero budget, the soft focus, the shaky camera, the scratched frame are the battle scars of your journey. So, never allow perfection to become your censor.

What kind of documentaries do you like to watch?

Usually, the subject attracts me, or sometimes the filmmaker. I look for integrity and passion in documentaries, not necessarily for polish, or technique.

Nowadays, there are lots of films, even well-intended ones, that are made with huge amounts of funding. When I watch a film, I discount technical prowess because that depends mainly on how much money has been put into the film. It doesn’t mean that good films cannot come out of such a process, but I’m trying to look at the material beyond the funding.

Your documentaries capture social and political movements that have been overtaken or crushed over the years. We are now ruled by a majoritarian government. Have your films had their desired impact?

In real terms, my films haven’t changed the world, but have certainly had enough of an impact for the state and right-wing goons to be unhappy and try to curb the screenings. Mostly the right-wing forces are told not to watch these films. Earlier, they used to infiltrate, watch and engage us in public. Now they are sent to attack them but never to watch them. Because the films can and do penetrate even brainwashed minds.

Today, it’s not just the state that we are worried about. It’s the mentality that has been created among large numbers of the population.

It’s difficult to have a healthy conversation. People are not watching the same things anymore. Everybody is in their own particular niche. Algorithms feed people what they already like. It’s hard to find common ground and common space to have healthy discussions.

Why persevere, then?

You have to do what you do, whether in India or elsewhere. Take Donald Trump’s America, where things are happening as blatantly as here. I’m confident that there will be a groundswell of opinion for change.

Already despite the Israeli propaganda machine, world opinion has changed and people are seeing what is going on. In India too, it will happen when there is a critical mass. We don’t have it yet, but that doesn’t mean that we give up trying to build it. It’s not a hopeless task.

I get enough positive feedback to continue, which means that I get people who have watched the films and who have changed their minds as individuals. I remain optimistic – but then we don’t really have a choice about this. Otherwise, we should shut shop and not do anything.

Any film of yours that you are particularly close to?

It’s always the last film that I made, because that’s the one I am showing the most and getting the most feedback for. Right now, it’s Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam.

Ram Ke Naam remains the most seen and most used film. Reason/Vivek is the most under-utilised film though its four-hour span gives you an over-arching story of the rise of fascism against the forces of rationality.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting