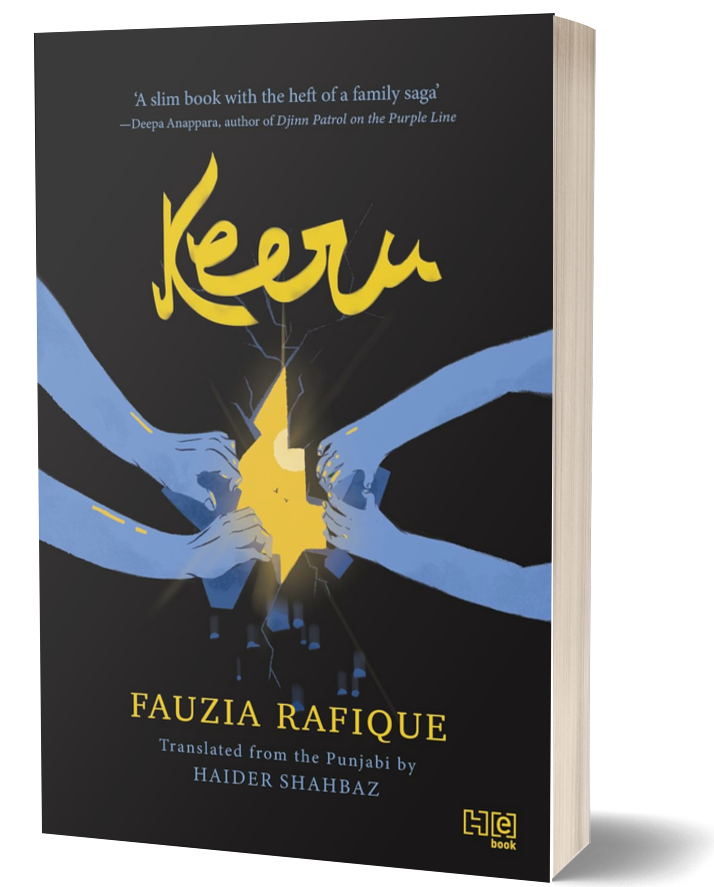

In her most recent novel, Keeru, the South-Asian-Canadian novelist and poet Fauzia Rafique brings to life characters and narratives from South Asia navigating love and community across caste, class, gender, and sexuality. It has been translated from the Punjabi by Haider Shahbaz.

In the novel, Muhammad Hussain Khan “Keeru” – named after insects – has come a long way since Pakistan, where he was hounded for his caste, and almost beaten to death on false charges of blasphemy. Having escaped to Canada, he is the owner of a small business, but the past has an inexorable habit of haunting him even in the present.

Told from the perspectives of five characters, each tormented by their past and desperately in pursuit of a home, Keeru tells queer and feminist stories as it overturns familiar tropes about migration and family. The novel is a celebration of resilience and our power to find family, love and hope – sometimes a world away.

In a conversation with Scroll, the author spoke of her work’s relationship with language, literary archives, and the diaspora. Excerpts from the interview:

Your work stands out particularly for its resonance with reality. We see it so closely in Keeru. It is grounded with references to social, legal, and cultural events in Pakistan and Canada. How precisely does this aspect blend into your creative work?

I think even if I am writing about something very small, in terms of the world, or very personal, or something that’s very limited, it still has a larger context. That context cannot be removed or ignored. Sometimes, I feel particularly in novels where engagement is quite large and lengthy, that some writers appear to be unaware of the larger context, or they have chosen not to make the reader aware of it. It is important for me to address this. No philosophy or observation occurs without its context. And of course, the “context” too has so many layers. This appears organically in my writing, so as not to interfere with the flow of the story. It remains as an undercurrent that can be recalled at any time by the reader and the writer.

Language appears as a prominent concern and theme in your writing. In Keeru, we see this through the character of Naila Aunty and her relationship with the three languages (Punjabi, Urdu, English). They reveal a lot about power and respectability, informing caste-, class-, and gender-based hierarchies. How do the relationships between these languages work with the context you speak of?

Language is very important to me. It is important to everyone, I guess. But in my work, it is one of the things that I keep addressing. I was brought up in Punjab, in a village where everyone around me spoke Punjabi. Then we moved to Lahore, and all those people speaking my shared language/dialect were not in my everyday experience anymore. And in the desire to make children “educated” and aspiring, the parents began to, or tried to, speak Urdu. And my education, too, was on the primary level in Urdu and then eventually in English. Punjabi was not a language to me at that point in my life. It was as if it were something that people who do not matter in the larger context use with each other. It is a class question, of course.

Also, I felt that there was a certain loss of language in my experience, and when I moved to Canada, this loss gained more importance. We lived in Toronto for the first ten years. I met many second-generation Punjabis who had lost their language. But of course, the language stays within you. I don’t know if I told you, but I wrote Skeena in Toronto. The novel had dialogues in English and Roman Punjabi or Urdu. At that point, Skeena was around 500 pages!

But then an editor I was working with asked me to remove Punjabi and Urdu. She said it would be cumbersome for the reader to read the same dialogue in two languages. I was reluctant because not only did I want to be able to make Punjabi characters express themselves in their own language, but also, I could see the possibility of the novel serving as a bridge for second-generation Punjabi kids. But in the interest of the novel, I did adhere to my editor’s decision and moved the Punjabi bits to another file, and that became the Punjabi Shahmukhi novel that you read, published by Sanjh in 2007. My desire to use Punjabi more extensively in an English novel was an attempt, maybe not so good, but still an attempt to create a bridge for the youth, to facilitate the use of Punjabi.

Also, our experiences of colonisation have done a lot of damage to South Asian languages. It encouraged Urdu, but all regional languages were suppressed, Punjabi being one of them. Within each language, there are movements, groups of writers, and scholars who want a systemic approach to language. They want sophistication by making certain things more valuable than others. So then, obviously, “nationalist” approaches that follow become detrimental to the thought. It is kind of like writing a ghazal where the format is so important that you must account for it first. Focus on the form before the thought.

In whichever language I write, I am told that my language is not proper. English, Urdu, or Punjabi. And that is because I do not agree with all the rules set by linguists, academics or literary critics. For me, the thought is much more important than the structure of the language. Of course, both are important but what do you want your main focus to be? It has to be on what is being said. How it is said can be the secondary concern. A lot of people don’t agree with that. I keep talking about it; otherwise, there will be no depth in our literature. And you see a similar intervention in my fantasy novel, The Adventures of Saheban, as well.

That’s interesting. Let’s speak of it then. When we think of language and context, it is interesting to note that both Keeru and Skeena open with verses from Shah Hussain. Adventures of Saheban is a playful take on the Punjabi lore of Mirza–Saheban. How would you then explain your work’s engagement with the classic Punjabi literary archive?

Yes, thank you for noticing that. I really learned a lot from and adore the Punjabi Sufi poets. Shah Hussain is my favourite. There is so much depth in his work that I can keep exploring and appreciating. His form of Kafi is short, not burdensome for the reader, and there is musicality too, because it is written for music. I enjoy Bulleh Shah in very different ways, and other classic poets too. I have learned a lot from them about life, language, and cultures.

And if we were to extend this question from classic to modern? In an interview elsewhere, you spoke of learning to write by reading. You mention Qurratulain Hyder, Krishan Chander, Ismat Chughtai, Prem Chand, and Rajinder Singh Bedi, among others, as your early influences. Keeru is impressive for its insightful opening into so many hierarchies and oppressions that otherwise you see dealt with in an isolated manner. What do you think is Keeru’s relationship to the contemporary Urdu and Punjabi texts that write around similar themes?

As you know, contemporary Punjabi literature is young. Especially the novel form, very few have been written, but of course, it is changing for the better.

Let me tell you that I could not finish some of the Punjabi novels I had started to read. Either it was boring or not relevant to me. At times, I feel, writers cannot, for some reason, express themselves originally, so they take up concepts from elsewhere, like English fiction, and try to apply those to their worlds. Or some writers use such a difficult bookish language that it is a chore to decipher and understand what they are trying to say. I don’t want to suffer as a reader. I like to read writers who say things frankly. This is not to say that the technique or nuance is not important, but to stress the importance of the theme or the subject matter. It is what someone wants to communicate to the reader. And if you make it so difficult to go through the story, it doesn’t work for me. I will not read it. In Saheban, I make fun of this through her biographer, Ego Feathers, who says such silly things but with an academic vocabulary, as if they are pearls of wisdom.

Maybe in a few years, when you have read more Punjabi literature, you will be able to compare and see how Keeru fares. Right now, I feel I just need to keep expressing myself without a care for the conventions.

One last language question. Anne Murph’s article, and now you, mention how you wrote Skeena side-by-side, co-creating it in English and Punjabi. Keeru itself exists now across languages. The initial Punjabi, the 2021 publication of the self-translated Urdu that you worked on, and now Haider Shahbaz’s very attentive English translation. What have these experimental processes revealed to you about translation as a process, as a method, and particularly working between these languages?

When I began to translate Skeena, the narrative parts that were not in Punjabi were my first major translated work. Earlier, I had only done Doestevesky’s adaptation for Aapey Ranjha Hoi for Pakistani Television in the 1970s; it was not a translation. Skeena’s narrative translation process was fascinating to me. It taught me that you cannot translate something that is not totally understood by you or something that is not written with absolute clarity. At that time, I had called such untranslatable constructions “lies”. Skeena’s translation made its English manuscript much better since ambiguous areas were clarified, and it helped remove what made it a lie. It made such a qualitative difference to the novel that I wanted to translate everything I write across languages to find the weaknesses in my writing. That was a miracle I experienced for myself as a writer.

The experience for Keeru was very interesting. I did not want to trust anyone with the translation at first. But Haider’s translations, when I saw parts of them, were so fascinating to me. It was a different perspective, a different take, and the draft was so good. Haider’s translation is brilliant and thoughtful. I enjoyed it. I have read his manuscript a couple of times. It was all very well done. I enjoyed the process of working with him, too. He was open to my feedback, and that mix of independence and consideration for the writer made his work even better.

Speaking of Keeru in particular, the resolve of the story, you said in a conversation elsewhere, is intended to be a joyful and healing experience. But both Keeru and Skeena unravel as our characters move away from their homes to Canada, making a home elsewhere. What do you think the story and its nuances would look like if these characters had never left Punjab or South Asia?

That seems very claustrophobic to me. Migration is a very important step in awareness. It encourages people to think more broadly, a bit differently. If you stay in one place, Pakistan or Canada, whichever that might be, the experiences will be limited. There will be something delicate that you won’t be able to know or feel. The experience of leaving has a lot of loss, yes, but that’s not the whole story. I live in Surrey, British Columbia, and there’s a huge migrant Sikh population here. We have three Punjabi writers’ organisations here that meet each month and have vibrant gatherings and readings. But the majority of our writers write about that sense of loss from leaving the homeland and the estrangement that is felt when adjusting to a racist society. I feel very differently. I think migration has losses but also a lot of gains. We can really enjoy the fruits of our experiences of encountering new cultures, languages, and people.

It was in Toronto that I came to know a few Indo-Caribbean women, for instance. I knew about migrations from South Asia, but never the other end. In short, I met more South Asian people here in Toronto, not in Lahore. And different people from all over the world.

Another important aspect of my migration experience is my personal gains as a woman. For reasons of our own political situation in Pakistan, or South Asia, or what used to be called Third-World countries, as a woman, it was a release for me to not be in Pakistan. It was a gain for me to be in a society where, of course, patriarchal oppression exists, but there is some protection still. I can walk at midnight without fear unless there are some troubles with racism. Unpatriotic or not, I will not give this freedom away.

For Keeru and many others, it’s a life-saving step to be able to migrate. Some people cannot even do that. The experience of migration is so rich that it cannot just be submerged by the loss of culture and people; it must go beyond that to its larger context. That is what Keeru’s story is too.

Yes, a character like Daljeet, for instance, from Eastern Punjab, would never make it to the story then. The concern in the novel then does become about navigating Keeru and Daljeet’s budding intimacy. But can the resolve ever be that easy?

Not just Daljeet, but also Bella, a second-generation youth, would not be able to feature in the novel. Regarding Keeru and Daljeet’s relationship, your question, “Can the resolve ever be that easy?” is pertinent. It also challenges the “wisdom” behind it. Let me tell you, for me it’s part wishful thinking and part a bright vision of the future. Indeed, this is not what usually happens when parents find out that one of their offspring is gay or queer. But in Keeru, a complete acceptance of gayness occurs as part of “quiet love”, a nurturing culture that develops between these “ordinary” people. And of course, the judgments that our societies give us to condemn others are also a class concern. They come from the middle class, the elite, who like to divide and create an “other” to use to further their own political interest. Vulnerable people such as Haleema do not have such desires.

Within the public spaces of Punjab, think of Shah Hussain’s darbar, you meet all kinds of people, and they are accepted. People in a village know that someone is gay, that someone is a different kind of person. There is a wider acceptability for differences because the vulnerable are trying to survive. Keeru’s mother, Haleema, in the novel talks of Saeen Manka, who is gay, or the school teacher she knew who was lesbian. She accepts him wholeheartedly. And most importantly, she loves her son so much that nothing else matters to her. The love of the mother, along with her experiences in Pakistan, is why the resolve was easy.

Haleema is such a strong character, and she becomes a pillar for this community. Somewhere in the novel, she says the poor have nine lives like cats and draws parallels between her own experiences of surviving layers of gendered, religious, caste-based violence.

Exactly. Though Keeru is pretty secular himself but if not for Haleema, the community would not have come together like it did. An individual intervention is all that you need sometimes.

Kaleemullah Bashir is a writer and translator from Pakistan, and currently a graduate student at UT Austin, where they study Urdu and Punjabi literary cultures.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting