Bitiya Murmu’s father died around 1980, when she was just a year-and-a-half old.

As the family members grieved their loss, they did not realise that for the next two decades, their lives would be shaped by the event. Her father had been the headman of their village, in present-day Jharkhand’s Dumka district, and he had owned significant amounts of land. But under the customary laws of the Santal Adivasi community, to which the family belongs, her widowed mother did not have any rights over the land.

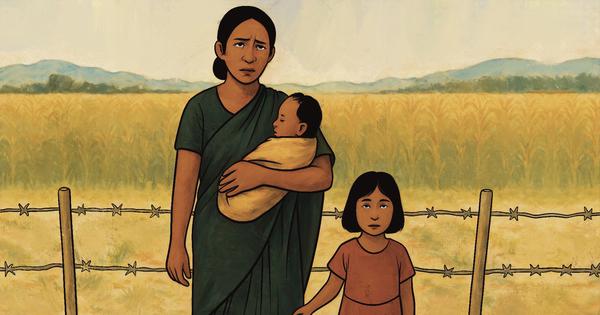

Murmu’s uncles wrested control of the land from her mother, leaving her and her three daughters at the mercy of her extended marital family. “My mother was subjected to grave mental torture by her in-laws, but she stayed put in my father’s house because she had nowhere else to go,” Murmu said. “With three daughters, she couldn’t return to her natal family as nobody would take her in there. She tried getting the local police and gram sabha involved, but nobody came to our help.”

The question of land inheritance rights of Adivasi women is a fraught one.

The Indian Succession Act of 1925 governs matters of inheritance for Christian and Parsi communities, while the Hindu Succession Act, 1956, applies to Hindu, Buddhist and Sikh communities and the Muslim Personal Law Act of 1937 applies to Muslims. All these laws contain provisions that give women some rights over land and other assets of their parents and spouses.

Scheduled Tribes, however, draw significant powers of self-governance from Article 244 of the Indian Constitution, and its fifth and sixth schedules, whose provisions include the prioritisation of customary law. On the question of inheritance, the Hindu Succession Act effectively ensured that these communities were bound to follow their customary laws by excluding them from the ambit of the act.

Thus, Indian jurisprudence has no specific laws that prevent tribal women from being disinherited from their paternal or marital families’ land.

Customary tribal laws are usually not codified in writing by the community, but are based on practices prevalent within a community. “For a practice to become customary law, it needs to be archaic, be in practice, be local but not universal, and not stand against public policy,” said Rashmi Katyayan, a senior advocate from Jharkhand.

Over the years, jurisprudence on the question of customary laws has also set frameworks for how and when they are applied, as well as limitations on them. In dealing with these laws, courts and governmental bodies often refer to documented information by anthropologists and other researchers on these practices.

The Jharkhand Judicial Academy’s handbook on land laws, for instance, includes an essay about the customary practices of the Santal, Munda and Oraon tribes. The handbook states that if a man leaves behind only daughters on his death, “their paternal grandfather and uncles take charge of them and of the widow”, while the deceased’s property is given over to the possession of the men. “When the daughters grow up, it is the duty of these relatives to arrange for their marriages and to give them the presents which they would have been given by their father,” it states. “When all the daughters have been disposed of, the widow gets the perquisites of a childless widow and goes to her father’s house or lives with her daughters.”

In a narrow technical sense, Murmu’s family was acting in accordance with customary law when they took away her late father’s land. “They basically wanted my family to be wiped away from there,” she said. “They tortured my mother in every imaginable way. They pressured her to get me and my sisters married off early.”

On July 17, however, the Supreme Court delivered a judgement that could serve as a precedent that would help Murmu and countless other Adivasi women who are battling for their land rights. In a legal battle that had been ongoing for more than 35 years, the apex court overturned previous judgements by a trial court, an appellate court and the Chhattisgarh High Court.

The case in question pertained to land that once belonged to a Gond tribal woman named Dahiya, who lived in Chhattisgarh’s Surajpur district.

Sadan Singh, one of the petitioners, told Scroll that the land in question was promised to his father by Dahiya, his paternal grandmother. However, after she passed away, her extended family took over the land and refused to bequeath it to Singh’s family.

“I am 36 years old today, my parents started this fight even before I was born,” Singh told Scroll. “We only fought for our rights, for what was promised to us.”

In the judgement, Justices Sanjay Karol and Joymalya Bagchi invoked the principles of “justice, equity and good conscience” and Article 14 of the Indian Constitution to uphold the deceased woman’s rights over the land, which her ancestors had bequeathed to her.

“There appears to be no rational nexus or reasonable classification for only males to be granted succession over the property of their forebears and not women, more so in the case where no prohibition to such effect can be shown to be prevalent as per law,” they stated.

The judgement also specifically noted that customs could not be used as reasons to discriminate against women. “Customs too, like the law, cannot remain stuck in time and others cannot be allowed to take refuge in customs or hide behind them to deprive others of their right,” it stated.

The judgement was widely welcomed and celebrated by feminist and Adivasi scholars and activists across the country. Writing for the Wire, Elina Horo, a feminist Adivasi activist, noted that it was “a vital turning point for Adivasi women in India”. Bina Agarwal, a feminist economist, wrote that it could be a “benchmark for extending gender equal inheritance rights to all tribal women in India”.

But reception to the judgement among Adivasi society was not unanimously positive. In Chhattisgarh, leaders from the Sarva Adivasi Samaj told the media that land inheritance rights for women would “wipe out old customs, incite conflict within the community and increase violence against women”.

Across the state border, Jharkhand, which has a prominent Adivasi intelligentsia, saw extensive online and social media debates on the matter. Numerous Adivasi activists, including women, were critical of the judgement. Some said that they would consider filing a counter-appeal against it.

Murmu fought a gruelling battle for her land, only to win a partial victory.

In the mid-2000s, by which time she was an adult, she first turned towards a self-governance and dispute resolution system envisaged under Adivasi customary law, known as Manjhi Pargana. At the first level, this would entail arbitration by the gram sabha. But after Murmu’s father’s death, her uncle became the village headman – this blocked her chances of getting the village gram sabha to arbitrate on her issue. “For 12 years, I kept asking villagers to convene a panchayat to adjudicate about our land and they kept refusing,” she said.

In 2016, Murmu approached the subdivisional officer court in Dumka seeking recognition of her family’s land rights. She recalled the magistrate telling her, “According to your customs, women don’t inherit land, so how can I rule in your favour? If you have an example of a woman who has inherited land, then please let me know.”

Disappointed, Murmu turned to the customary resolution system again, and informed her gram sabha members that she planned to approach higher traditional courts. At this, she said, “They held a meeting and told me that I can’t have the land because Adivasi women don’t inherit land.”

Murmu went ahead with her plans anyway, and in 2018, approached the More Manjhi, a traditional court comprising the heads of five or more neighbouring villages.

The court ruled in her favour. She recounted that it told her uncles, “There is a proper way in which you can take your late brother’s land. Did you look after his family at all? Did you treat them as your own? You never supported them. Then what right do you have to their land?”

But though the traditional court ruled in Murmu’s favour and her uncle and others returned her land to her and her sisters, neither they nor government officials provided them with a title deed for it.

“I asked the Circle Officer for a map of the land and written documentation that I have rights over it, but he never gave it to me,” she said.

Instead, she explained, the village panchayat issued her a letter that spelled out her basic rights over the land – this letter made clear that the panchayat considered her rights over the land as limited. “It said that I can use the land for agriculture to feed myself, but the day I die it will be returned to my father’s family and my children cannot inherit it,” she said. “I cannot sell or lease the land for any purpose.”

In response to her ordeal, Murmu entered the field of social work in the 1990s, and has since worked on Adivasi women’s rights, among other matters, in the Santal Pargana region. Today, she runs an NGO called Lahanti and also leads the Ekal Nari Sangathan, or “single women’s collective”, which advocates for women’s land rights.

“It is said that Adivasi society is more gender-just and women have all the rights,” she said. “But, where are they? I’ve come across hundreds of women who have been harmed by their community. They have nobody to turn to.”

The Supreme Court judgement has given hope to Murmu. She said she was considering approaching the courts again. “For years, we didn’t have a precedent, but this new ruling can change things,” she said.

Not all Adivasi women support the judgement.

Activist Rosalia Tirkey, a member of the Jharkhand Adivasi Women’s Association, advocates for women’s rights in other areas, but opposes the grant of land rights for women.

She explained that in most Adivasi communities in Chotanagpur, villages typically have a few dominant clans, each of which collectively owns their plots of ancestral land.

When Adivasi women marry, they typically leave behind their natal family’s clan and join their husband’s clan, Tirkey said. “My marital home is in Mahuadanr and I also spend time in Ranchi,” she said. “I seldom have the time to return to my natal home which is in Simdega. This applies to most Adivasi women. If we did inherit land, we would not be able to look after it.”

Thus, she reasoned, there was a high likelihood that women would sell off their ancestral land.

“Adivasis look at land differently from others,” she said. “For us, it is an essential part of our identity given to us by our ancestors. It is not property to be sold for commercial purposes.”

She also argued that granting these rights to women could lead to people from outside a village taking over its land.

This particular fear is also rooted in the widespread anxiety that an increasing number of Adivasi women are marrying non-Adivasi men. Traditionally, marrying outside the community is frowned upon and women, especially, are sometimes excommunicated if they do so. Some Adivasi activists have even called for Adivasi women to be stripped of the Scheduled Tribe status if they marry outside the community.

“If this judgement turns into a proper law, it will definitely open a new avenue for non-Adivasis to loot Adivasi land,” said Tirkey.

On the other hand, many feminist Adivasi activists argue that currently, Adivasis’ land ownership systems are not truly communal.

Rather, they argue, during the British era, a private property regime that favoured Adivasi men over women was introduced and formalised. “If Adivasi land is communitarian, then all of it should be in the community’s name,” said Anita Gari, a social worker and member of the Ekal Mahila Sangathan. “But our land documents were registered under the name of a male ancestor. Today, it is only the common lands which are communitarian, everything else has become individual property.”

Indeed, in a paper on Munda Adivasi women’s land rights in Jharkhand, legal researcher Shalini Saboo noted that “Most of the land is raiyati, that is, under private ownership. There is very little land available which can be termed as commons.” Thus, she pointed out, the question of land rights for tribal women usually pertained to “privately owned land in which their male relatives have ownership”.

In fact, activists argue that over the years, Adivasi men have sold off large tracts of Adivasi land to non-Adivasi communities and corporations – despite legal provisions such as the Fifth Schedule, the Chota Nagpur Tenancy Act and the Santal Pargana Tenancy Act which bar non-Adivasis from buying or capturing Adivasi land.

“Take Ranchi for example,” said Gari. “There is hardly any Adivasi land left here. How have non-Adivasis bought this land? It is the men who sold their ancestral land, since women didn’t have rights over it.”

Adivasi women, Gari argued, have a special bond with land and are often at the forefront of fights to prevent takeover by state or corporate entities. She cited the example of a recent agitation in the village of Nagdi in Ranchi district, where women “came running first to save their land”.

“Those who say that Adivasi women will sell off their land if they get rights to it consider women to be disloyal and characterless,” she said.

Others have noted that Adivasi women have historically suffered immensely as a result of violence that accompanied industrial development, and were left particularly vulnerable because of their lack of land rights.

In an interview with Shalini Saboo, the late Adivasi activist Rose Kerketta observed that when the state acquired land in the 1950s in Ranchi for the Heavy Engineering Corporation, Adivasi men were paid compensation money and given low-rung jobs – following this, many abandoned their wives and children and left them destitute. She observed that “if tribal women had inheritance rights, the entire family could have survived and that women could better utilise the compensation package”.

A collective of Adivasi feminists made similar arguments in a press note on the recent judgement. “Land is the foundation of Adivasi identity, yet women’s identities have long been confined to their relations with men – as mothers, sisters, wives, or daughters,” they stated. “The absence of women’s ownership rights over land has denied them an independent identity and stripped them of many other rights.”

The Supreme Court’s recent judgement is a reversal of the position it has taken in the past on the same question. In 1996, the court heard a case in which two sets of petitioners contested the denial of inheritance to women under Adivasi customary law.

The apex court sought the recommendations of the Tribal Advisory Board of undivided Bihar, which comprised legislators and parliamentarians who represented the state’s tribal areas. The board stated that while “tribal society is male dominated” it did not mean that women were “neglected”. It noted that married women and widows held “usufruct rights” over their husband’s property, referring to the right to use and cultivate land without destroying it.

The board concluded, however, that granting inheritance rights to women would “enlarge the threat of alienation of the tribal land in the hands of non- tribals” and that it was the rights of transfer of inheritance given to women that led to “malpractices like dowry and the like prevalent in other non-tribal societies”.

In its judgement, while the court did not grant the petitioners inheritance rights, it did recognise the petitioners’ right to life, which included the right to livelihood – thus, it ruled that the immediate female relatives of the last male tenant could use their family’s land as long as they remained dependent on it for their livelihoods.

The new Supreme Court judgement offers some hope to women and families who are seeking greater rights over their land. But accounts from the ground also suggest that the opposition to them is so deep-seated that they will face a long and difficult struggle.

Anita Gari, the social worker with Ekal Mahila Sangathan, a non-profit which works with single women, knows this from personal experience. Her husband abandoned her and her daughter in the early years of their marriage. Over the years Gari has filed several cases, seeking maintenance payments from her husband to help her raise their daughter – so far, she has been unsuccessful. “I have singlehandedly raised and educated my daughter and married her into a good home,” she said. “I’ve never received a rupee from my husband as support.”

These anxieties are compounded by her uncertainty over her land rights – she presently lives in a house built on her husband’s ancestral land, which she fears could be sold off to a third party in the future. “I have heard my husband has begun selling his ancestral land,” she said. “I could become destitute in the future. If I had legal rights over this house, this would not be the case.”

Last year, when Gari approached lawyers in Ranchi to fight for land rights, she was told that Adivasi customs did not allow women to inherit land. “I would like to safeguard some land in my daughter’s name for her to fall back on if she ever needs it,” she said.

Gari is educated and works in the development sector – this enabled her to fight for her rights, she said. In contrast, it was much harder for unlettered women in rural areas to take up similar struggles. “If the law upheld the rights of Adivasi women, then those who need it would use it and the rest would let things remain the way they are,” she said. “Look at the Hindu community. Women inherit property, but very few actually end up taking it. But at least they have legal rights to fall back on. The current system has left Adivasi women without any support.”

Lalita Hembrom, who lives in Kalajhor village in Dumka district, sought Bitiya Murmu’s help in her own fight for inheritance rights a few years ago.

Lalita is the eldest of three daughters in her family. While a younger sister married and moved away, she and her sister continued to live in their natal family house after they married, along with their husbands. “Among our people, there is a practice of ghar jamai, wherein the groom moves into his wife’s house after marriage,” she said.

Both Lalita and her sister’s husbands died a few years ago. Since then, she said, her cousins have been harassing them to force them to leave the house and give up their share of the family’s agricultural land. “ “Every year, they pick fights over the agricultural land when it’s sowing season,” she said. “We are beaten up and verbally abused.”

Fed up of the violence, Lalita even tried approaching the circle office for help. “They took some money and asked us to reach a compromise, but the abuse has continued,” she said. While Lalita does not have children, her sister has a son. “Once we die, what will my nephew do? He will be left destitute,” she said.

There were other women in similar situations in the same village. “They keep telling us that women don’t inherit land, but where are we to go?” said Lalita’s neighbour Sabina Hembrom, who explained that her four uncles were harassing her for staying with her natal family. “It’s not just us, you’ll see this in many houses,” she added. “When those who don’t have sons pass away, their daughters have to live at the mercy of their male relatives.”

In some cases, even after women have secured their land rights through courts, they continue to be denied them on the ground.

Among these is a case involving an Oraon Adivasi woman named Prabha Minz, who lives on the outskirts of Ranchi. In 1989, Minz inherited a plot of ancestral land a few kilometres from her home, through a written will.

In 2000, Minz found out that some of this ancestral property had been sold off to a third party by men claiming to be her cousins. “It was all the work of agents who deal in buying and selling land through corrupt means,” she said. “I wouldn’t have faced this if I had brothers.”

When Minz challenged this sale in a civil court, the sellers argued that Minz had no rights over the land, since tribal custom does not allow women to inherit land.

Minz spent the next two decades fighting for the land in lower courts, with no success – she also dealt with intense pressures from those around her. “The land agents were from my village, so they turned people against me,” she said. “When my daughters were young, we would be attacked when we would try to cultivate our land. We are farmers and we live off the land. Where else were we supposed to go?”

Minz challenged the unfavourable verdicts of lower courts in the Jharkhand High Court. In 2022, the high court ruled in Minz’s favour – but to her dismay, the buyers of the land did not vacate the land, and continue to occupy it even today.

In the two decades, Minz said she had spent large sums of money on court expenses. The financial and emotional stress took a huge toll on her family. “Since childhood our life has been full of sorrow,” her daughter Suman said. “If we were sons, they might not have targeted our family.”

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting