“Aphantasia” describes a condition in which one is unable to create mental images: the imagination has no visual register – it is blank.

The exhibition titled After-Aphantasias at Delhi’s Bikaner House is an attempt by six Sri Lankan artists to craft a different imagination of the conflict that tore apart the island nation for nearly 25 years.

Sri Lanka’s civil war is often remembered through the language of politics and military strategy. But art has the power to shift the focus to personal experiences, loss and remembering. After-Aphantasias is an artistic expression of grappling with the ramifications of the conflict, and a search for clarity that aims to challenge “dominant narratives”.

These artistic interventions are significant once one grasps the roots of the conflict.

There had been long-standing tensions between Sri Lanka’s Sinhalese majority and Tamil minority. The Sinhala Only Act of 1956, which made Sinhala the sole official language, became a major flashpoint for discriminating against Tamil identity, culture and livelihoods. A Tamil militancy rose on the back of grievances among the Tamil minority, fueled by communal divisions and discriminatory policies.

In July 1983, in a major escalation, members of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam ambushed an army patrol. An anti-Tamil pogrom, known as Black July, led to a massive exodus of Tamils. The civil war ended in May 2009 when the Sri Lankan armed forces defeated the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. But it exacted a devastating in cost of tens of thousands of lives and a violent, traumatic legacy.

The group show at Bikaner House by the Shrine Empire gallery features the work of Anoli Perera, Chandragupta Thenuwara, Jagath Weerasinghe, Kingsley Gunatillake, Muhanned Cader and Pala Pothupitiye.

On display at the same venue is a solo show by their compatriot Hema Shironi.

The first artwork that one encounters in After-Aphantasias is Anoli Perera’s Left Behinder, a series of tapestries made using printed images on cloth, appliqued cloth, stuffing, nylon cloth, charcoal pencil and acrylic.

For Perera, her artwork as a way of holding memories, exploring her relationship with her mother, whose memories are fading, and creating a tangible, enduring connection.

Perera explores the structural violence against women during conflicts, highlighting how their experiences are often overlooked in broader historical accounts. She combines fabric with metal and mesh in her works, which challenge patriarchal norms and focus on themes of motherhood, “separation, connectedness, and intimacy”.

Perera’s Book of Remembered Lullabies combines multiple media to create a six-page series. Each is set within a wallpaper-like recurring pattern giving it a domestic setting. Cultural elements and fragments of text in the composition add layers of intimacy and history.

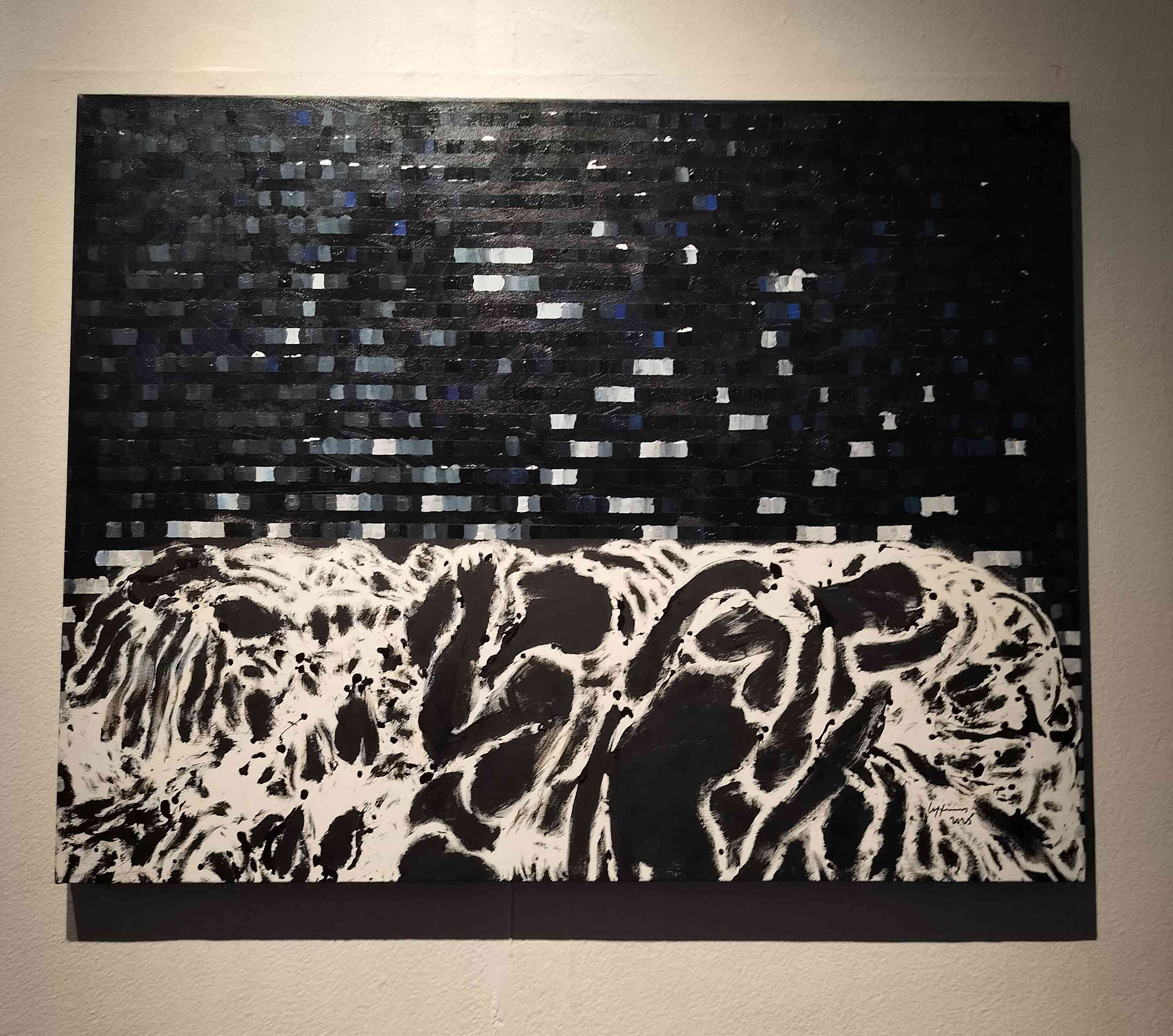

While Perera’s art focuses on the gendered effects of violence, Jagath Weerasinghe addresses the masculine aspects of conflict and war.

His acrylic works on canvas and paper, such as Under the Dark Sky, Among the Rubbles and Boots, Snakes and Mikes, are made with “thick, vibrant and determined brushstrokes”. These works depict imposing male bodies in “frenzied contortions”, talking about the political violence.

Pala Pothupitiye examines the glorification of war heroes by juxtaposing them against figures like Superman, symbolising power and vested interests.

Installations by Kingsley Gunatillake, which combine books with copper soldiers, explore the complex relationship between violence and peace.

Gunatillake uses books as a deliberate and powerful way to highlight the burning of the Jaffna Public Library on May 31, 1981. The books become symbols of loss and violence.

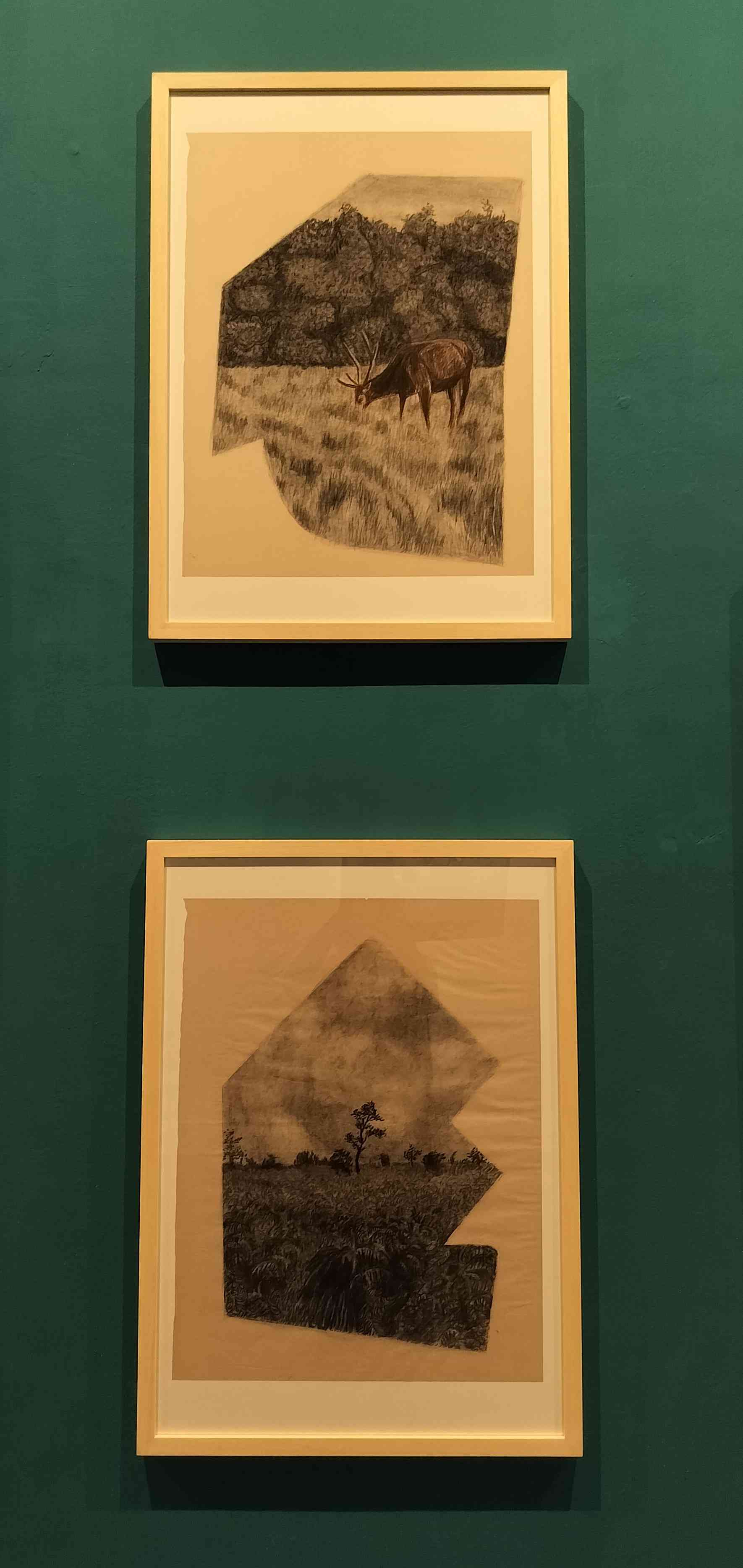

Muhanned Cader takes a different approach, turning to the natural environment. His work depicts the land, sea and sky as “silent witnesses” and “victims of violence”.

In Glitch, Chandragupta Thenuwara aims to make viewers see beyond what has obscured the truth and encourages them to seek a deeper understanding of the reality.

The exhibition confronts dominant narratives that often downplay the severity of the conflict. By bearing witness through their art, these artists use memory and reflection as a form of resistance, making their work a record of the past and a challenge to widely accepted narratives.

In conflict, it is mostly ordinary people, especially women, children, and marginalised communities, who bear the deepest suffering and whose voices are rarely heard.

Though the exhibit focuses on the ethnic conflict and war in Sri Lanka, it resonates with a shared history and experience across borders that speaks to understanding human consequences and cultivating empathy. This perspective is as relevant today at a time when conflict continues to shape the lives of human beings.

The exhibition is also significant because it is rare to encounter one that focuses entirely on artists from a South Asian country. Presenting contemporary Sri Lankan artists in a central space like Bikaner House creates room for voices and stories that are too often overlooked.

Wandering through the artwork, I kept reflecting on the different ways conflict can be understood, through memory and through loss. It left me with the realisation that conflict lingers with people and environments alike, continuing to shape how we see, remember and reflect.

All photographs by Andleeb Shadab.

After-Aphantasias is on view till September 25 at CCA, Bikaner House, New Delhi.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting