Arundhati Roy’s memoir of her mother is called Mother Mary Comes to Me. My own mother, whose life I similarly reflect on, was Narayani, named after the protective mother-goddess, whose presence resonates with compassion and words of wisdom.

My husband always refers to her in our conversations as Narayani, not “your mother”. This diminutive woman of steely will, Confucian ideals (without reading Chinese or Confucius), was the woman who taught me everything – some from embryo.

What does one owe our mothers or, does that debt just accumulate with no debtor’s knock on your door? Because it is given with love yet reminding you always of your sense of obligation to return it through the good you can do through life’s bitter and winding alleys? Narayani was my mother, my stalker, my conscience, my doppelgänger.

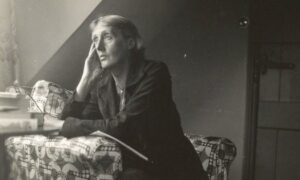

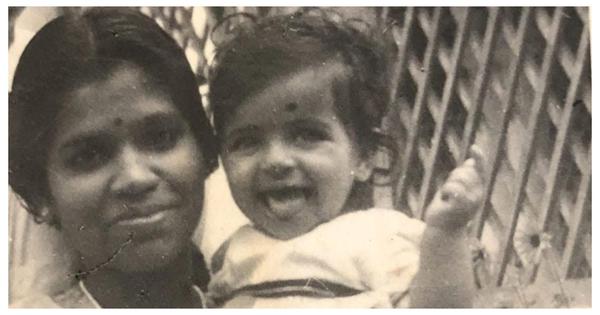

She left us long years ago. Twelve to be exact. I hold two images of her. One, in a sepia photograph of a 23-year-old, gossamer-thin, her hair long and lustrous, in her wedding sari. In the other image, she lies on her pyre, gray and wasted, in an abandonment of her cosmic soul, her oceanic mind switched to silent mode. How do you keep these two images as one? Yet my mind keeps them together, impossibly, and stubbornly.

She was Narayanikutty, BA always spoken in full, the first woman in her family to have a university degree, mathematics with honours, no less, numbers and abstractions balanced in a mind that should have belonged to the future but was bound to the household, to the repetitive routine of cooking fires and family expectations.

A contradiction: the diminutive woman of steely will, the one with the degree that glittered with its false promise, and the same one who lived within the frame of feminine bondage. Her brilliance smouldered quietly, expressed in a different calculation: how far the rice would stretch, the dresses she stitched for us, her children, our homework, the rationing of dreams. That contradiction does not resolve itself; it carries forward, unresolved in me, as if my own life were the equation she never solved. I am the unfinished theorem of her life and mine.

Yet she also sang. Not with melody, but with words, with numbers and with stories. She was the spinner of the wonderworld. In the long evenings, after we had said our prayers and eaten, she became a storyteller. Krishna and Sudama, their friendship woven through parables of humility, Orpheus and Eurydice, a myth she carried across borders without ever stepping beyond Indian shores. And then, unexpectedly, the many wives of Henry VIII, their names reeled off with relish, as though Tudor politics were as close as our neighbourhood disputes.

She taught me Confucian ideals without knowing either Chinese or Confucius, order, and duty without dogma. Her imagination was of the ceaseless explorer, the tireless seafarer, even as her body never left the country of her birth.

She taught me to write. A clumsy sentence, she dismantled. A weak phrase, she cut down. She pushed me to imagine, to create, to weave with words. Writing was the way you imprinted your soul on others. In some atavistic state,

I remember her hand closing around mine when I was two years old, guiding me into Thunchan Parambu, birthplace of Ezhuthachan, the father of Malayalam. There, at the Vidyarambham where children trace their first words, it was she who ordered the gift of language for me. It was my initiation not only into literacy, but into her song.

She never spared me. After every maths exam, I copied my answers onto the question sheet before handing it in. At home she became examiner, divine calculator, reeling off solutions without pause. Accuracy was duty. Excellence was never enough. She carried her unreachable standards folded into her saree pallu.

Her vision was always more than sight. She could see through me; past the masks I wore. She scolded me for careless pleats in a sari, but the correction was never only about clothing – it was about dignity, survival, about being seen in a world eager to diminish. Her barbs were sometimes cruel, but cruelty was her language of urgency. She was small in body, but the weight she bore – responsibility, lament, unspoken longing – was immense.

It was many years later that her dementia came. But first, I must have my say, mother. I must speak to you. You are my target, my aim, that centre-spot of the universe.

So here is my refrain:

Debt is suggestive of a ledger, payments made and to be returned. About collection and score-settling. Motherlove and economics are hardly consonant. It is patient but also paradoxical, an invisible force of gravity, shaping your positioning, your orbit. Can you repay gravity? No, because it is all-consuming, the pull of the origin mother. You fight it, but you also cannot resist its g-force, the stronger you accelerate against it, the higher you experience it, whatever speed, whatever direction.

Yet that repayment is counted in terms of resonance. You resonate within, in my deepest recesses. Your ferocity, your stubbornness, is my reservoir. I am obliged to you for that reason, for that weight I carry, but also the gifts I treasure because of that debt. That weight is an honour to carry, it accumulates by the minute, it is my inheritance. Narayani, the woman, and Narayani, the myth, the goddess, overlap in my consciousness, both luminous, and impossible to relinquish.

The puzzle persists. Do we carry our mothers forward, or do they carry us still. Mothers refuse to leave, to go away. They haunt us, they own us, we cannot exorcise their spirits. Long after they are gone, their eyes sear you, even when they are beyond vision’s range. It is vision more than sight alone. It is a haunting persistence.

They lodge within you, and their presence is both tender and tyrannical. They have somehow infiltrated the architecture of who we are. It is muscle memory, it is moral reflex, the voice in our heads, our editors-of-gestures, or words, even before we have shaped them for the world we inhabit. At all times, they are hovering over your conscience, teaching you the intuitive, to survive in a world that scrutinises women constantly. We are constantly enacting our mothers.

This leaves me with a profound riddle; do we live our own lives or is our sovereignty the constant object of intrusion by our mothers. Dedication is how we bind ourselves to our mothers, but possession flips that bond, as they lodge deeply in our souls and speak and act through us.

For me, you, Narayani, are that spirit. Your vision, more than sight, your unforgiving corrections of me and mine, your fervour, these were the terms of your dedication. Your possession of me in afterlife, continuing to live as a force within me. Your love becomes the law, and I am not free of you, and never will be.

There is a confluence of two forces here. Matriliny and mitochondria. Two sides of the same inheritance. Matriliny, as in Kerala, is traced through the mother: family names, property inheritance, identity. In biology, mitochondria, tiny powerhouses for our cells, carry their DNA exclusively from our mothers. My mitochondria are a direct line from Narayani, unbroken across countless generations of mothers.

These powerhouses march down our maternal line, a secret torch passed from mother to daughter, stretching across our pasts and our futures. Every breath you take, every contraction of your muscles, every firing of your neurons is powered by that maternal inheritance.

Metaphorically, and in molecular terms, my mother lives in me, not just remembered, but burning within my cells, a booster, a thrust ensuring my life’s balance. Matriliny shapes my place in a web of family relationships, where names and property have flown through women. But mitochondria shape the very functioning of me, the unseen fire. Together they weave an intricacy that feels soul deep. But the chain halts with me. I bore only sons. The mitochondrial flame that burned in her, and burns in me, will not pass to daughters of my own. The maternal song ends here. I am both vessel and terminus.

When her dementia came, the stories were disjointed, the numbers collapsed without meaning. One day she looked at me, eyes clouded, and asked, who are you? She had forgotten me. But the grip stayed, beyond any human imagination. Her days are long ended without her releasing possession of me. Her contradictions are not reconciled in me.

Narayani is my conscience, my doppelgänger, that haunting presence mirrored in the engines of my cells, in a potent cocktail of memory and metabolism. This is a cosmic symmetry that echoes the myth of the eternal mother, sung in texts like the Narayaneeyam. Both myth and molecule agree here: mothers do not leave. Imagine this, within ourselves, the colonies of our mother and the mothers before her. That is how I return, always, to Narayani.

The days are long vanished. She is gone. But the songs she taught me remain: myths and equations, discipline and dignity, the craft of language itself. Songs woven with her tears, which never left her eyes, and with mine, which have never dried.

I recall a verse from the Narayaneeyam,:

“ചിരവത്സലാത്മകാം കമയതീം ഭാരതഭൂമി ചിരാത്മീനോ ധാരിണീം …”

Chiravatsalātmakaam kamayatīm bhāratabhūmi chirātmīno dhāriṇīm …

The mother whose love is as vast as the earth, who holds the hearts of her children through countless ages.

And from across another world, Dvořák and Heyduk carried the same refrain in Songs My Mother Taught Me:

“Songs my mother taught me, in the days long vanished;

seldom from her eyelids were the teardrops banished.

Now I teach my children each melodious measure;

Oft the tears are flowing from my memory’s treasure.”

Two traditions, two tongues, one truth: the mother never leaves. Her refrain persists—whether in hymn or lullaby, in algorithm or story, in the very mitochondria that power each breath.

She was Narayanikutty, BA – mathematician and homemaker, critic and storyteller, woman incarnate. And the mother who taught me to write.

She is Narayani, departed, yet she is the one who never left.

Nirupama Menon Rao is a former foreign secretary. She has served as India’s ambassador to the US and also to China.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting