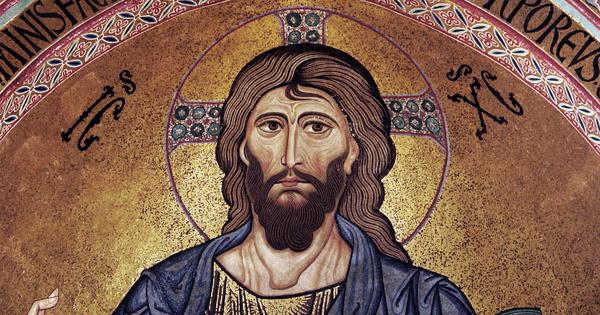

In The Second Book of Prophets, Malayalam writer Benyamin employs his formidable storytelling to explore one of history’s most mythologised figures: Jesus Christ. What sets it apart from other hagiographic retellings is that Benyamin doesn’t deconstruct just for the sake of it – he offers a thoughtful, bold and tender reimagining of Jesus as a man shaped by faith, fear, and courage, far from the gilded certainty of religious iconography.

The novel narrates how, for centuries the Jewish people have suffered under Roman rule, holding onto the hope that a liberator from the tribe of David will arise to lead them to freedom. Jesus of Nazareth is not eager to claim this role. But after the execution of John the Baptist by Roman forces, he reluctantly steps into the void, carrying with him the weight of prophecy and the yearning of the people plagued by conflict, hopelessness and mistrust. What follows is not a linear tale but a chorus of fractured testimonies.

As the novel progresses, we learn about Jesus’s rise, which does not go unchallenged. The tribe of Benjamin, wary of Davidic influence in Jerusalem, sees his growing presence as a threat. Instead of rallying behind him, they align themselves with Roman authorities in a plot to bring him down. Though all of them suffer under the same occupying force, they remain deeply divided by tradition, law, and social structure. The religious leaders, lost in their power and resistant to change, are not ready to accept Jesus’s radical message of compassion, humility, and equality, fearing it will upend the fragile order they maintain.

A prophet rooted in politics

The internal divisions within the tribes run deep. The social, religious, and moral codes and standards continuously prevent a unified front against oppression. At the same time, the religious and social elite, protective of their power and traditions, deeply fear figures whose spiritual roles are deeply intertwined with political influence and activity and whose messages carry strong political weight or consequences. In a society which is marked by inequality, violence, and rigid orthodoxy, prophecy is dangerous speech, and a prophet is someone who disrupts the status quo.

Perhaps most radically, Benyamin’s Jesus is not a miracle-working messiah, but a disruptive force in a rigid, unjust society, working towards restoring human dignity. He’s not depicted as divine or omniscient. He questions, doubts, and at times feels unworthy of the expectations placed upon him. This radical yet deeply emotional humanisation does not diminish him; it deepens him. In Benyamin’s prose, spiritual greatness is not born of sacred mandate, but from the inner struggle to act with integrity in spite of it.

One of the novel’s most compelling qualities is Benyamin’s unwavering attention to the voices that history often sidelines – especially women. Mothers, sisters, widows, outcasts are rendered with intellectual and emotional depth, offering a relationship with the reader outside the romanticised tropes. Women in the novel communicate, challenge. They are given room to doubt, to believe, to conspire, and to protest where traditional gospel narratives place women in the background. These voices are what lend the narrative a raw, relatable honesty, suggesting that truth often lives not in hierarchy, but in lived experience. This political and theological complexity forms the heart of the novel, where Benyamin brings these characters to the fore, where they are not relegated to the margins as mere followers or passive witnesses.

The Second Book of Prophets leads an inquiry into belief, carefully escaping the snare of dogma, and instead turning toward the fragile, human moments that question faith, belief, and truth. What does one believe when doubt persists? What happens when faith becomes a burden? Can faith survive failure and betrayal?

One of the most haunting moments of the novel is Benyamin’s careful portrayal of Jesus’s emotional and physical struggles. It is not simply attributed to a divine decree. Rather, it is the people around him – his family, his followers, his detractors – who create the trembling tension of doubt and fear, unsure whether anything miraculous, divine or otherwise, will happen at all. The prose resonates with longing – for transcendence from scepticism, fear, and ambition.

The cost of faith

Benyamin does not resolve this tension easily. He doesn’t fill the novel with easy saints or overly tormented souls; instead, he lets the ambiguity breathe, often threading it with a faltering sense of hope. His novel is deeply respectful of spiritual longing. In a world where religious narratives are often fiercely guarded, depicting Jesus as uncertain, fallible, and political is a risky artistic endeavour. Where this novel succeeds is in how Benyamin critiques not faith itself, but the ways in which systems of power have co-opted faith and drained it of its original, radical spirit. That tension between belief and doubt, power and truth, is what gives the novel its lasting emotional and intellectual power.

Ministhy S writes in her note as the translator, “More often than not, books choose us – not only as readers, but also as co-travellers in their journey across the magical universe of languages.” This sentiment echoes in her masterful translation. She captures the lyrical subtlety of Benyamin’s prose, and her choices reflect a deep fidelity to the original, coupled with a careful sensitivity to the rhythms of language and the content that are intimate, probing, and resonant with spiritual complexity, especially in the dialogues. What gives the novel its emotional force is its vulnerability, and the translation captures that with remarkable fidelity.

Reading The Second Book of Prophets in a time of authoritarianism, disillusionment, and spiritual uncertainty, one finds that it is not simply a novel about Jesus. It ushers the reader into a space where doubt, faith, fear, and courage can coexist. It is also a novel about us: the cost of dreaming, the power of solidarity, and the question of what we are willing to risk for hope, justice, and truth. Benyamin leaves readers with these questions, and it is this openness and the refusal to reduce faith to fanaticism, gives the novel its lasting impact. In describing the fragile hope that dares to imagine a better world, and the cost of holding onto that hope in the face of violence, failure, and betrayal – Benyamin has done something rare: he has made an ancient story feel urgently, achingly alive.

The Second Book of Prophets, Benyamin, translated from the Malayalam by Ministhy S, Simon and Schuster India.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting