There was a time when Takia Meerasian, a Sufi shrine in Lahore’s walled city, was the “hatchery” for Hindustani musicians, says the late Pakistani critic M Saeed Malik in his book The Musical Heritage of Pakistan. For here, in front of an unforgiving audience, was where you proved your mettle. Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, Amir Khan, Narayan Rao Vyas and just about every legend performed here and in other baithaks and takias of Lahore.

But many purges later – political, social and cultural – that legacy departed, leaving not just Takia Meerasian, but much of Lahore and Pakistan. Classical music, as we know it in India, as khayal, dhrupad and thumri, are now on the margins of the country’s culturescape. Where you find some fine and delightful representation of it is in its popular music – in its ghazals, qawwalis and raga-rock.

Why the syncretic and shared classical music tradition exited Pakistan has been the subject of multiple inquiries, including the acclaimed 2007 documentary by filmmaker and author Yousuf Saeed, Khayal Darpan. Continuing this line of investigation is the work of Kabir Altaf, a young Pakistani American scholar. His book, A New Explanation for the Decline of Hindustani Music in Pakistan, based on his dissertation for a Master’s degree, was published recently by Lahore’s Aks Publications.

Altaf, a trained vocalist, argues that the commonly cited reason for the decline of classical music in Pakistan – that it was a casualty of the newly formed nation’s search for a distinct cultural and religious identity – does not fully explain the shift.

“These reasons are valid but they offer only a partial explanation,” he said. “For instance, why did classical forms like khayal, thumri and dhrupad face erasure, while the heavily classical ghazal and qawwali survive and thrive?” If the Islamic argument is valid, all these light forms should also have been impacted, as was the case in Afghanistan, he argues in his research.

Altaf believes that one crucial factor is often underemphasised in the analysis – the flight of the moneyed Hindu and Sikh elite during Partition. These were the business, landed and merchant families who had formed the core patronage base for classical music in Pakistan.

“Historically, classical music has been seen as high art,” said Altaf. “You need to be acculturated to it. You often heard lay audiences complain that ‘we fell asleep in the bada khayal but woke up for the sargam’. Or that an alap by Roshanara Begum was not ‘catchy’ enough. So when the elite of, say, Lahore left, an entire constituency for this music started dying.”

This happened, he says in his research paper, not just in metros like Lahore and Karachi, but also in smaller trading and manufacturing towns like Shikarpur in Sindh, which famously hosted vocalist Mallikarjun Mansur twice.

Some of the most legendary names in Hindustani music, spanning across gharanas, moved to Pakistan after the Partition of India – including vocalists Amanat and Bade Fateh Ali Khan of the Patiala gharana, Roshanara Begum of Kirana gharana, Hafeez Khan of the Talwandi dhrupad gharana, Nazakat and Salamat Ali Khan of the Sham Chaurasi gharana, masterly sarangiya Bundu Khan and vocalist Ghulam Hassan Shaggan of the Gwalior style. Farida Khanum, now known primarily as a ghazal singer, also came from the Patiala lineage.

But this post-Independence swell declined after the first 10-15 years, say old timers. The downturn could be seen across the field – in the number of renowned artistes emerging from the country, in the number of academies dedicated to teaching classical music and the students learning it, and in the air time it received. As part of this broader decline, Altaf also points to the “decimation” of Pakistan’s once-thriving instrument-making industry.

Biggest casualties

Though he grew up in the United States, Altaf has clear memories of stories about his grandmother’s cousin being taught by an ustad of the Agra gharana. The family was steeped in music. Later generations learned from Aqeel Ahmed Khan of the same tradition. Today, in their American home, every family member sings or plays an instrument.

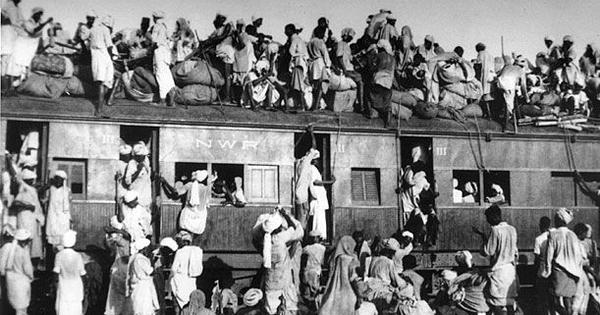

But the very history that shaped Altaf’s musical inheritance was also marked by rupture. Partition violently splintered the region, and among its many casualties were the syncretic cultural traditions that straddled both sides of the border. Gharanas and artistes whose lives and work had moved with ease through undivided Punjab were suddenly forced to choose sides.

In his essay Fled Is That Music, author and archivist Yousuf Saeed reflects on the deep roots of classical music in undivided Punjab, with Lahore as its cultural epicentre. The Mughal emperors had championed the high arts here from the 16th century onward, followed by the Sikh rulers from 1764, particularly under Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s reign. Gharanas such as Patiala, Talwandi, Kapurthala, and Sham Chaurasi thrived in the region. The very first school of the Gandharva Mahavidyalaya chain was set up in Lahore under the guidance of Vishnu Digambar Paluskar – long before it spread across the rest of undivided India – helping cultivate an appreciative audience in the city.

“At Partition, about seven million Muslims from Indian provinces such as Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Maharashtra, brought to Pakistan their local dialects, cultures and, of course, classical music practices – including those from established gharanas of north India,” writes Saeed.

It was a time of painful churn. Some who migrated managed to make strong careers for themselves. Others like Bundu Khan found it hard to cope with the pain of displacement, while the great Bade Ghulam Ali Khan moved to Pakistan but returned to India, reportedly upset over poor remuneration.

For the classical musicians who did remain in Pakistan, the early years after Partition were not immediately harsh – the Islamisation crackdown under the Zia regime was still decades away, as were the wars that sharpened the cultural divide between India and Pakistan. Yet, even in those early years, there were visible signs of unease – questions were already being raised about whether music was inappropriate as per the tenets of Islam.

“The contested status of music in Muslim societies has led to a conflicted state of mind among some musicians,” says Altaf in his dissertation. “While deeply devoted to their art, they sometimes feel that they are participating in an activity contrary to the teachings of their faith.”

He recounts a story about music director Jhande Khan in an Urdu literary magazine. Khan taught sitar to his daughter but at times, overcome by “religious fervour”, he would unstring his instrument and renounce music – only to fall into depression and return to it, though never for long.

In Khayal Darpan, Lahore-based critic Sarwat Ali points out that classical music was among the biggest casualties of Pakistan’s earliest identity building exercises centred on the question – what makes us different from India? This question hit khayal and thumri the most because dhrupad, with its overarching Hindu themes, had already been pushed to the margins. Women musicians had it worse: they were forced to reinvent themselves as overtly pious and genteel just to be allowed to practice their art freely, as documented in scholar Fawzia Afzal-Khan’s book Siren Song: Understanding Pakistan Through its Women Singers.

The situation turned surreal soon. “In this process of the Islamization of culture, song compositions and raga names with references to Hindu deities were abandoned,” writes Saeed. “Nevertheless, some artistes continued to sing those ragas, but with altered names – Shiv Kalyan, for instance, became Shab Kalyan.”

Tarana, qawwali and ghazal remained largely untouched because they did not have overt Hindu associations, though qawwali and tarana both have deeply melded roots. Still, gharana musicians clung on to their arts in this phase.

Altaf points to 1971 as the year when everything changed. The war acutely sharpened the anti-India sentiment and the fate of classical music took a sharp downward dive. Writes Altaf: “As a consequence, many musicians began actively encouraging their children to gravitate to acceptable genres like ghazal or pop music. Well-known classical musicians from East Punjab who settled in Sindh and Multan turned to folk genres such as the kafi and sought to meld diverse styles. A few prominent artists with a legacy reputation, like Ustads Salamat and Nazakat Ali Khan, were able to negotiate the stressful times and the absence of state support through occasional concert tours in the West.”

The Zia regime drove the final nail into the coffin, curbing classical broadcasts, cracking down on the arts and stirring public hostility against them.

Crippled art

Altaf argues that these factors, critical as they were, could not have entirely crippled the art. He maintains that there was just not enough pushback against the rising tide of xenophobia. Pakistan’s crackdown on music as an expression of Islamic hardline, he says, was never all-encompassing as Taliban’s, which decimated all music in Afghanistan every time it won the country’s reins.

A less explored facet of the bloody Partition exodus, he reasons, is that although a similar number of people crossed the border from each side, the economic profile of those leaving Pakistan was “assymetric”. Those who moved to India were the well-heeled and elite Hindus and Sikhs, he says, citing data from Ilyas Chattha’s 2011 book Partition and Locality: Violence, Migration and Development in Gujranwala and Sialkot. For instance, in pre-Partition Gujranwala, Hindus and Sikhs, though in smaller numbers, paid 90% of taxes and, in Sialkot, they ran most businesses, while Muslims mostly made up the working class.

This inequality of income and wealth was evident in much of Pakistan, affecting not only metropolitan centres like Lahore but also the landholdings of smaller rural areas. When the Partition struck, and the violence began, along with the exodus of the affluent classes went the patronage for classical music.

“The cultural impact of the population transfer was exacerbated by the replacement of the elite of one religion by groups of a different religion that were predominantly from low-and middle-income backgrounds,” writes Altaf.

The cities in Pakistan that did receive elite refugees from India – such as Lahore and Karachi – were the ones where classical music fought longer to remain relevant.

“Classical music withered away because there was really no one to put up their hand for it and because it was not nourished from below,” Altaf writes.

Still, classical music did inform popular music in Pakistan in a big way. It shaped the distinctive style of ghazal singing popularised by Mehdi Hasan as well as the powerful performances of legendary qawwals like Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. And while the taans and gamaks of fusion musicians – many of them scions of the ustads – are light on the ears, they did not let the whole legacy die.

Malini Nair is a culture writer and senior editor based in New Delhi. She can be reached at writermalini@gmail.com.

This article first appeared on Scroll.in

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting