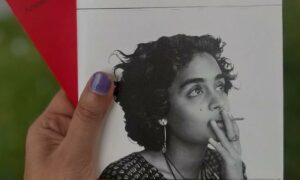

While reading Arundhati Roy’s Mother Mary Comes To Me, it is best to be armed with the author’s own statutory warnings in title case:

Estha and Rahel, the seven-year-old twins from Arundhati Roy’s Booker-winning first novel The God of Small Things (GOST), had tried to protect themselves with these simple rules. Reading GOST, you knew, somehow, that Roy was inextricably tied to the siblings. Mother Mary Comes To Me is an affirmation of this, as well as of the dangers that shadowed her and her brother Lalith Kumar Christopher Roy (LKC), growing up under their mother Mary Roy’s watch.

In her dedication, Arundhati writes that their mother never said “Let It Be” as Mother Mary did in The Beatles anthem. It is not clear how she addressed her in person, but in this book, Arundhati refers to her mother as Mrs Roy – and as “Mart” Roy only at the end, as an insider joke – throughout, putting a safe distance between them.

Mary Roy was a force of nature – brilliant, accomplished and efficient, she had a nasty, often unpredictable, temper, and was capable of immense generosity and cruelty. We learn early on that Mary Roy’s father too was a violent family man. “He whipped his children, turned them out of the house regularly, and split my grandmother’s scalp open with a brass vase,” writes Arundhati. Mary had inherited this violent streak from her father. As a single mother, she was constantly engaged in conflicts with her family and frequent doses of indignity were forced upon her by them, which she proceeded to unburden on her children immediately.

While Arundhati’s love (somewhat irrational under the circumstances) and attachment for the only parent she knew as a child hug her narrative like a warm blanket, the sudden and unprovoked verbal assaults from her mother would leave her shaken:

“When she got angry with me, she would mimic my way of speaking. She was a good mimic and made me sound ridiculous to myself. I clearly remember everything about every instance she did that. Even what I was wearing. It felt as though she had cut me out – cut my shape out – of a picture book with a sharp pair of scissors and then torn me up.”

These “diverse iterations of hell” in the first half of Mother Mary Comes To Me knock you back with a visceral punch every few pages. And while you ricochet, a knot of pain settles inside you. This has often been the impact of Arundhati’s prose on her readers, and her memoir is no exception. Reading it you begin to see where her power springs from, not to mention all those title case emphases in her early writing. You must, therefore, look out for lurking dangers around every corner just as the Roy siblings had to, growing up. There are sentences that jump out of the text, tearing into you with brute force. Brace for it, but also look forward to the humour and heart in her text throughout. Arundhati’s memoir is a dangerous ride, with sharp bends and steep inclines, which makes you suppress either a scream or a loud laugh. The sometimes-unintentional comic relief is very welcome.

There are brief moments when Mary Roy betrayed a heart – but she quickly reverted to her default state of being angry and righteous, and continued with her bullying and rampaging. Very early on, she had firmly drilled into Arundhati the need to be proper and do the right thing always. Arundhati’s life seems to have been spent showing the middle finger at the former and embracing the latter, a gift for her readers and admirers.

Mary Roy’s ruthlessness and “wrath against motherhood” are as fascinating to her daughter as it is to her readers. However, what is extraordinary is Arundhati’s deadpan act of putting down the bare facts, steering clear of judgment or victimhood, and never losing empathy for her aggressor, though she is no Gandhian. Roy lovingly calls her mother a gangster, never a monster.

Mary Roy confessed to loving her children “double” in the absence of their father and Arundhati obviously tried to believe her. Yet she was left baffled and scarred by the force of her mothering. You can feel Arundhati’s own struggle to fathom her mother’s behaviour, dangling helplessly in her pincer grip. You sense the powerful bond between them throughout, but also feel her desperate desire to make a break for it. The lifelong admiration she felt for the extraordinary Mary Roy mingles with her unshakeable fear for her protector. For Arundhati, Mary Roy ultimately becomes her “shelter and her storm” – and she remains caught in this duality for far too long. This turbulent past is funny, sad, heartbreaking and moving in equal measure, as is her memoir.

Arundhati’s story is ultimately incomplete without her mother’s large, often grotesque, presence and her shadow remains cast on her whole life. What the Booker Prize-winning author is today for millions of readers – with her “seditious heart”, her enormous empathy for the wronged, her clear-eyed vision and fearless voice – was obviously shaped by the remarkable Mary Roy. No part of her adult life would have been the way it turned out, if it was not for her mother. Including Arundhati’s aversion to a predictable status quoist life.

Memories from childhood

Roy begins her book with her landing in Cochin after her mother’s passing and then, with a long backward reach of her memory, returns to her infancy. Her maternal grandfather – an imperial entomologist and wife beater – owned a holiday cottage in Ooty. He had been estranged from his wife and had died the year Arundhati was born. Young Mary Roy took shelter with her small children in one half of it. Mary had walked out of her marriage with Rajib Michael Roy, a planter at an Assam tea estate.

Micky Roy, as he was widely known, came from a well-known Bengali family in Calcutta. He was addicted to alcohol and Mary considered him a “Nothing Man” – she had later confirmed to her children that she “married the first man who proposed to her” to get away from her abusive father. Unhappy in her marriage, Mary grabbed her children – the boy of four-and-a-half and the girl of three – and reached her late father’s cottage. Obviously, their home in Kottayam district, where her brother and elderly mother lived was ruled out, given their acutely conflict-prone relations. In Ooty, Mary relied on the kindness of their old staff and a teaching job she had found.

Among Arundhati’s earliest memories is her mother’s persistent asthma (aggravated by Ooty’s cold, damp climate), which planted in her heart the fear of her losing her (she would agonise over Mary Roy’s fragile health until her passing, sixty years later). But soon the trauma of another incident overtook this – her uncle G Isaac and her grandmother turned up to evict them from squatting on her grandfather’s property. This probably triggered Arundhati’s lifelong fight or flight mode – she describes vivid memories of accompanying Mary Roy, along with LKC, running through their town to find a lawyer.

The word fugitive is deployed by Roy when writing about her unsettled childhood. Turns out that the twins’ memory of their parents fighting in GOST to get rid of their children – “You take them, I don’t want them” – was not fiction after all. Arundhati and her brother were mostly left to fend for themselves after Mary Roy was saddled with them. Though it’s hard to feel her pain, there was no end to Mary Roy’s hardships at this stage: bedridden with asthma, she was out of a job and soon ran out of money. The children were left “undernourished and developed primary tuberculosis”.

Mary Roy eventually swallowed her pride and moved to the gorgeous Kottayam countryside, the village Ayemenem, with her children, where they started living with her sister, not far from her mother’s house. She went on to start a school in a makeshift Rotary Club space on top of a motor workshop. As the school grew in size and reputation, she moved the institution to the top of an abandoned hill, after the legendary architect Laurie Baker helped her build a permanent school building. It gained the status of a glorious institution over the years, and Mary Roy stood tall over it as a fierce and committed educationist.

Somewhere between her role as a tough loving mother, a quarrelsome daughter/sister and a formidable educationist, she was also a bona fide troublemaker locked in a property dispute with her family; this ultimately turned her into a minor legend. The humiliation and injustice of being nearly evicted from her father’s house led her to move the Supreme Court to strike down the Travancore Succession Act of 1916.

With the ultimate scrapping, in 1986, of this discriminatory law, she had won herself and the women of the Syrian Christian community equal rights to their father’s property. This, obviously, was a crucial step in the fight for women’s rights in India, particularly in the context of property and inheritance. Arundhati’s frank admiration and pride for the exceptional woman that her mother was, is evident in the passages where she recounts this episode.

Earlier, as she grew into her teenage years, Arundhati had begun to understand her mother, her frustrations and fury more and more, but that could not inure her to them. Young Noonie (her nickname) bore it until she no longer could and decided to run away at the age of 16. Meeting Laurie Baker earlier, she was drawn to architecture and joined Delhi’s School of Planning and Architecture (SPA). She arrived in the city with a knife in her bag but very little money. Life continued to be hard, but removing herself from her mother’s vicinity had become a necessity – the only way she could continue loving her, she confesses. The distance she had created allowed her to both understand her mother better and build defences against her for the rest of her life.

In Delhi, she began a new life, making friends, finding love, dreaming about being free. Here we encounter a diverse cast of charming characters who shape her wanderer’s life: Golak, her first friend, Jesus Christ, the now famous architect with whom she later entered into a not entirely legal marriage, Carlo, the enigmatic older Italian man, the watchman with the gold tooth at SPA, some of whom reappeared in the film In Which Annie Gives It Those Ones.

Although she would stay away from Mary Roy for seven years, her mother remained an abiding presence in her life. Arundhati describes living with a “brown moth” as her constant companion since her childhood days. Hundreds of miles away from Ayemenem, she would pause – she felt the moth crawl all over her heart every time she found herself shackled by human bonds. Her safe place became “dangerous”, and she would escape. She returned to the trenches, cutting loose bonds of love, escaping the safety and warmth of homes, to embrace her “fugitive” life.

The making of Arundhati

In the second half of Mother Mary Comes To Me, we see the making of Arundhati Roy, the actor, scriptwriter and author. Her personal hell recedes when she finds love and purpose, which eventually give way to her grief and horror at the unravelling of India. The political becomes personal.

Her hilarious run-ins with dull, humourless bureaucrats, her battle for “consent” alongside Phoolan Devi during the making of a Channel 4 feature film, her brave reportage from the Narmada Valley, the precarious days and nights spent walking the forests of Dantewada are narrated with the gaze of a hand-held camera. Unwilling to say sorry for a crime she had not committed, she ends up in Tihar Jail for one surreal night, and then finally her Kashmir journey that formed the core of her novel The Ministry of Utmost Happiness begins.

Some of the passages in this section are just as unsparing and relentless as her childhood trauma. The rampant, outrageously brutal punishment handed out to several “enemies of the state” is chronicled with blinding force in her prose. Arundhati ends the chapter “Walking with the Comrades” with these lines: “One of the women had been dragged [by the paramilitary] over the rough, stony roads by her hair until her scalp came off her skull. I couldn’t tell whether she was Comrade Niti or someone else. Comrade Niti did have long, beautiful hair.” She had come to know Comrade Niti earlier.

The funny, bizarre and sometimes dangerous bits of her writerly life feel like an action movie script in this pacy, dramatic half. Her own gangster-like romp through life – leaving in its wake a bunch of dazed and confused people – is both funny and heartbreaking. There are vivid glimpses of her private life, interspersed within this, told with courage and conviction. Her father, Micky Roy, a supremely lovable drifter whom she encounters later and loses, makes a cameo appearance.

The wonderful men whom she made her own are vivid characters revealed with tenderness. She writes about them with an aching warmth, her memories of Pradip Krishen and his daughters being hauntingly beautiful. And then of course, her creepy old friend, the brown moth, turns up, and she must rupture every bond and leave. There are inconvenient parts of her story, sections she could easily have erased, that are told with Arundhati’s trademark honesty. Not only does she choose to retain them, she owns them unflinchingly.

Arundhati Roy is as unafraid to bring judgment upon herself as well as her mother throughout her memoir. Despite everything – her often ruinous escapes and attempts for self-protection, backed by imperfect logic – she endears herself and her decidedly unconventional family throughout, making you travel with her. I fought back tears as I read the passages of sibling love with LKC, his Esther to her Rahel. Your heart will ache at the kindness and love they are capable of, and how both ultimately retained their sanity and found themselves. How they loved back Uncle Isaac, their Rhodes Scholar uncle, locked lifelong in battle with Mary Roy, later rendered bankrupt by his litigious sister (their clashes are genuinely funny).

And then you will think about that person who birthed the siblings, gave them wings, and showed them how not to live an unremarkable life. The one who ultimately unleashed Arundhati Roy, her guerrilla heart, mind and all, upon us.

Sanghamitra Chakraborty is the author of Soumitra Chatterjee and His World.

Mother Mary Comes To Me, Arundhati Roy, Penguin Hamish Hamilton.

This article first appeared on Scroll.in

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting