In 1981, 60-year-old Tayub Ali’s family moved from Morigaon to a region on Assam’s border with Nagaland.

“As there was no land in Morigaon and no way to earn a living, we came to Uriamghat,” he said.

Both Assam and Nagaland claimed this region on the banks of the Regma river as their land.

Like Bengali-origin Muslim families who came before him, Ali cleared forests at the foothills of the Naga Hills and began farming there.

The settlers struck up a transactional relationship with the Nagas in Rajapukhuri village near Rengma forest. “We grew paddy and other vegetables for the Nagas and gave them half the crop,” he said.

Amzad Ali, a 62-year-old who moved to the same village in 1981, said the Bengali-origin Muslims, sometimes also derisively called Miya Muslims, were cheap farm labour for the Nagas.

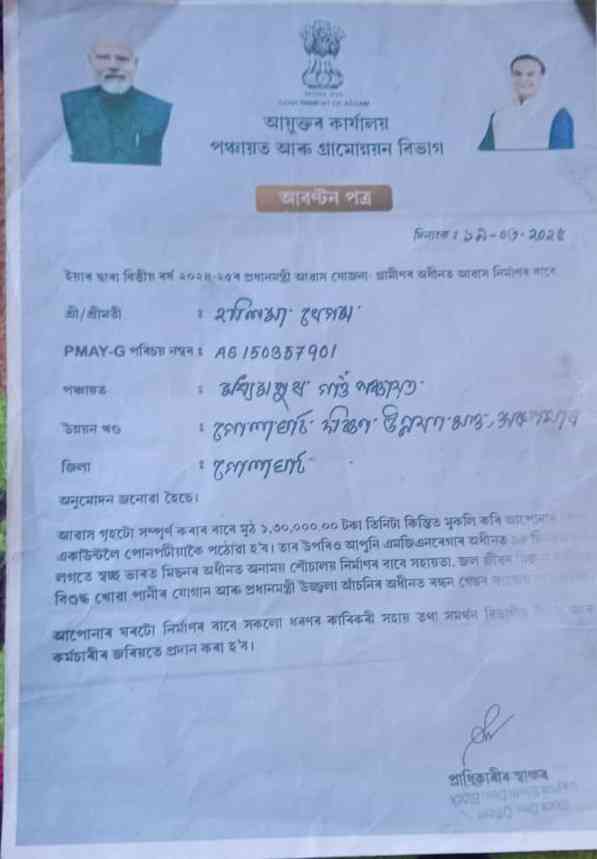

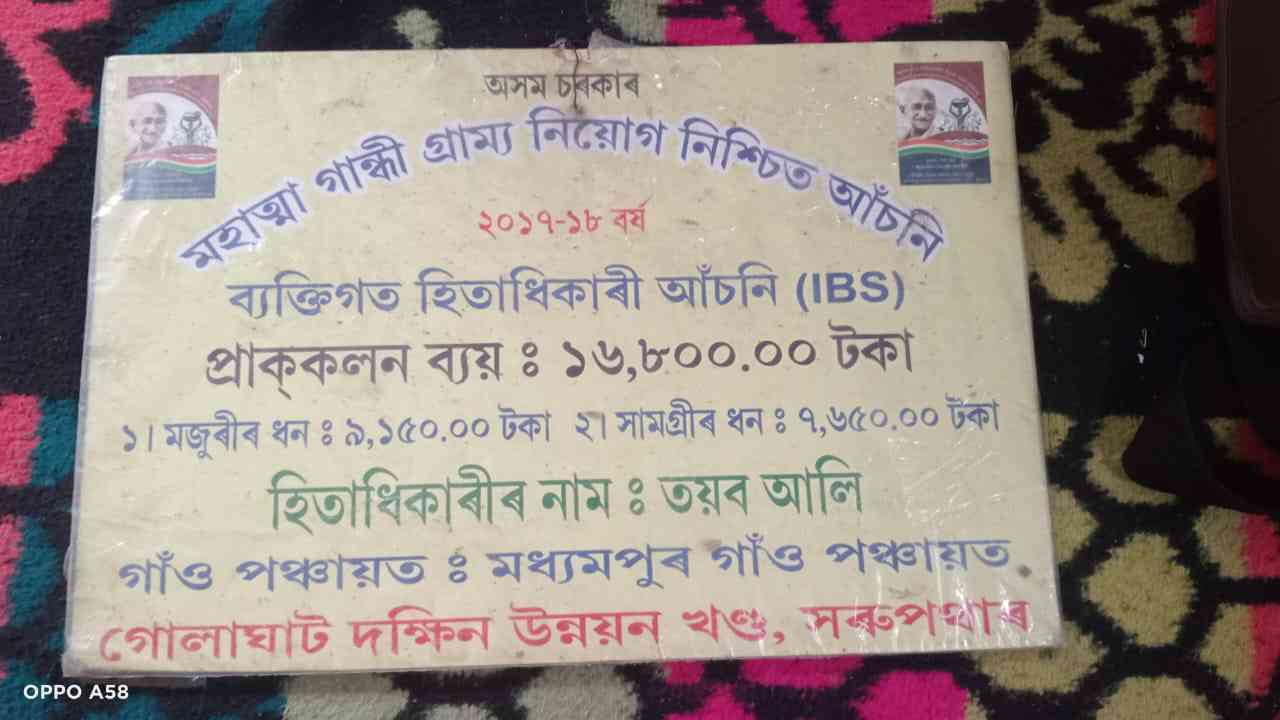

Both farmers said they were encouraged by the Assam government and the Golaghat district administration to expand their settlements. “The Assam government of the time encouraged us to settle here. The government made schools and roads for us and provided us welfare schemes,” Amzad said.

Tayub Ali recounted, “After a few years, we stopped paying any tax to the Nagas as the Assam officials told us that the land was not Nagaland’s but came under the central government.”

Over decades, the settlements around the Rengma and South Nambor reserve forests turned into organised villages with roads, schools, anganwadi centres, electricity, clean water supply, and access to government welfare schemes – all sanctioned and maintained by successive Assam governments, said residents.

Other communities – Bodos, Adivasis, Misings, and Assamese Muslims – also moved to the villages.

In July, however, the Himanta Biswa Sarma government initiated several demolition drives in the border region to “reclaim forest land”.

Over three weeks, the government cleared more than 4,300 structures that had allegedly been built on forest land, leaving around 2,200 families homeless. Tayub Ali and Amzad Ali, who had lived in the area for over four decades, were among those whose homes and holdings were razed.

As has been the feature of Assam’s evictions by the Bharatiya Janata Party government, the demolitions singled out the Bengali-origin Muslim community.

“Why were our Nepali, Assamese and other non-Muslim neighbours not evicted?” asked Mohammed Fakar Uddin, a 27-year-old resident of Rajapukhuri village. “They are also living on forest land.”

Nchumbemo Ovung, the head of Tchujajenphen village in the adjoining district of Wokha in Nagaland, told Scroll, “The Miyas had settled on our lands with the help of the Assam government. The same government has evicted them now.”

‘We feel unsafe’

While there has been popular support for the evictions of Miya Muslims across the state, the demolitions have left behind a sense of disquiet in this frontier region, as Scroll found on a visit to the area.

A resident from an ethnic Assamese community, who lives in Uriamghat, said, “With the Miyas gone, we feel unsafe, we are afraid the Nagas may attack us.”

Days after the eviction, Naga residents were spotted in the areas cleared by the Assam government, claiming the land as their own.

Soon after the eviction, a group of families from the Mising community in Negheribil village along the border sought the deployment of security forces as a Naga village council had claimed jurisdiction over the area.

The evictions have also revived the six-decades-old dispute with Nagaland and driven a wedge between residents of the state. “Himanta is playing with fire,” a former border minister of Nagaland told Scroll. “His aim may not be to provoke the Nagas but his actions have done just that.”

The dispute

The Assam-Nagaland border conflict, arguably India’s ongest running inter-state boundary dispute, dates back to December 1, 1963, when Nagaland was officially declared a state.

Nagas claim about 12,833 sq km of Assam’s territory, contending that it historically belongs to their tribes. Uriamghat falls in one of the six disputed sectors.

The government of Assam maintains that these areas have been under Assam’s administrative care for more than a century, and no contradictory direction has been given to them by the central government since.

In 1985, at least 32 people were killed after police forces of the two states fired at each other across the disputed border fence at Merapani, 34 km from Uriamghat.

Wochamo Lotha, a 55-year-old resident of Liphanyan, a Naga village adjoining Uriamghat, claimed that after the violence in 1985, several communities “of doubtful origin” were “pushed into these areas by the Assam government” to assert their claim on the land.

“Despite it being a reserved forest, Miya Muslims, Bodos and Nepalis were allowed to construct houses with government funding.”

He added: “Some of the settlers bought our land and some of them forcibly occupied it.”

Abu Musa Syed, an Assamese Muslim farmer in his 40s, told Scroll that families from Assam had fled the area after the Merapani clash. “But the Assam government told us to return. They said the government will provide CRPF protection.”

Hemkanta Phukan, a retired professor of English in Golaghat, made a similar assessment. “They [Bodos, Miyas, Adivasis, Nepalese ] were working as border protection,” he said. “It is said that they were settled by the Assam government in the border areas to protect [land] from the Nagas around.”

In 1978, several Bodos were settled in the region by the Janata Party government headed by Golap Borbora, followed by Adivasis – and then the Miyas, Phukan said. Borbora’s son, however, has denied the claim.

In a representation to the Assam government, 41 families from two villages in Uriamghat protested their eviction. “Our forefathers settled here alongside families from diverse backgrounds and played a pivotal role in safeguarding the frontier lands from external encroachments,” they said.

Assam forest officials, however, said the claims had no validity. “It is an irrelevant matter,” a senior Assam forest official told Scroll on being asked if the displaced had been settled by previous governments.

“We consider it as an encroachment even if one has encroached on forest land for 40-50 years,” the official said. “It is not our lookout if someone had encouraged or settled these encroachers.”

The Assam government has filed an affidavit before the Gauhati High Court, stating the same.

“Even if, for some inaction on the part of the forest official, some persons in the past were allowed entry in the reserved forest area, who continued to stay there, they would have no enforceable right against the government when such eviction drive is undertaken,” the state principal chief conservator of forests told the Gauhati High Court after the displaced people from Uriamghat moved court.

Bengali-origin Muslims singled out

In the last nine years of Bharatiya Janata Party rule, about 17,600 families – the majority of them Muslim – have been evicted from government land, according to data provided by the state revenue and disaster management department and respective district authorities.

In 13 drives since June 16 , the Assam government demolished the homes of about 6,138 families, 90% of whom are Bengali-origin Muslims, also called Miya Muslims.

In Uriamghat, too, a similar pattern played out.

Scroll found that 10 villages inhabited by Muslims of Bengali origin in Uriamghat were razed while 31 non-Muslim villages, all situated within the same forest belt and exhibiting identical patterns of land use and settlement, were left unscathed. The residents of the latter were not served any eviction notices.

In some villages like Anandapur, 30 houses belonging to Muslims of Bengali origin were demolished, while 30 homes of their non-Muslim neighbours were left standing. In Silonijan village, action was taken against only three Muslim homes, as the rest of the non-Muslim households remained undisturbed.

“Is it that only Miyas live in the Rengma reserve forest?” asked Renben Humtsoe, the headman of Chandlashung village in Nagaland and a BJP member. “There are Cacharis, Nepalese, Adivasis, Manipuris and many other communities. If they want to evict and chase the encroachers, they should have evicted everyone. Why only Miyas? It is totally wrong.”

On August 11, 41 Bengali-origin Muslim families of Madhupur and Anandapur villages submitted a representation to the Golaghat district authorities protesting against the “selective” and “communal” eviction drives in Rengmai reserved forest.

The affected residents told Scroll that they have become victims of Chief Minister Sarma’s politics.

“They demolished three mosques in my village but the temples were not broken,” Fakar Uddin said. “Sarma is only doing Hindu-Muslim [polarisation] to win the 2026 elections.”

However, the forest official claimed that “everyone has to leave the forest land sooner or later” if they are not entitled for rights under the Forest Rights Act of 2006 which grants forest land and resource rights to forest-dwelling communities. “It is a matter of time,” he said.

Naga claims

In the Naga villages along the disputed belt, too, there was widespread suspicion of the Assam government’s “unilateral” action.

The former border minister alleged that the Assam government’s actions invited the charge of contempt of court. The Assam government had filed a case before the Supreme Court in 1988 to resolve its border disputes with Nagaland. The case is still pending.

“How can they carry out evictions in a disputed area belt when the matter is in the Supreme Court?” he asked.

Several Naga villagers Scroll met alleged that the Assam Police and forest department personnel had encroached into the Nagaland side on the pretext of conducting evictions.

“The evictions have only widened the fault line between the two states,” said Mhonjan Humtose, a social worker of Ralan, which shares a boundary with Uriamghat. “Assam should not touch Naga’s boundary and the eviction should not be used to grab our land.”

The Nagaland government’s silence in the matter has also raised questions.

“There was no discussion with the people or civil society groups,” the former border minister of Nagaland told Scroll. “The eviction was announced only by Himanta Biswa Sarma.”

After the demolitions, the Assam government announced a large-scale tree plantation drive to restore and “reclaim areas of the Rengma Reserve Forest to their natural green cover”.

But the decision led to protests from leading Naga groups like Ralan Area Lotha Hoho and Yamhon Area Public Organisation.

A day later, on August 15, the Nagaland government said a “joint eviction drive” was initiated to ensure “non-unilateral action” and to maintain “status quo” in the area.

On August 24, as tensions ran high, the tree plantation programme was abruptly cancelled following a closed-door meeting between officials of both states.

“If something happens next, be it violence or anything, only the Assam government is responsible,” said Renben Humtsoe, the BJP leader.

The aftermath

In the wake of the evictions, several skirmishes have been reported, leaving the region on the edge.

Dipankar, an Adivasi activist from Uriamghat, told Scroll, “Our people are afraid because of past conflicts with the Nagas in which many of us died.” In 2014, at least 20 people died in a border conflict.

Two Assamese Muslim residents of Madhupur village, who have been living in the border area in Uriamghat before the 1970s, told Scroll that they are now afraid for two reasons.

“All the Miya Muslims were evicted and about 90 Assamese Muslim families were spared,” 70-year-old Mujaar Ali told Scroll. “But there is no certainty that they will not evict us next.”

Ali added: “Secondly, the Nagas are claiming the land belongs to them. We were afraid of their aggression.”

Abu Musa Syed, his neighbour, added: “Only Muslims were forced to take a risk and settle in such areas. But now, we are afraid. There is no sleep at night.”

This article first appeared on Scroll.in

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting