It was the autumn of 1619. The days were clear and cool, perfect for travel. The royals had returned from western India some months prior. After her hectic travels and constant imperial engagements, the empress was weary. The emperor began thinking about a pleasure trip to Kashmir, as a restorative for his beloved Nur. He had been there twice with his father. He often described it as the garden of eternal spring. We can imagine Jahangir telling Nur about the beauty of Kashmir, its countless waterfalls, the sweet-smelling roses, violets, and narcissi, the views of lofty peaks.

And so, the royal cavalcade of the emperor and empress set out again from Agra, headed toward the tall Himalayas. Queen Mother Harkha and other royal women were in the procession. So were Prince Shah Jahan, as well as the empress’s elderly father and brother and nobles, officers, stewards, attendants, servants, and soldiers. Mahabat Khan, the loyal general, recently appointed governor of Kabul, escorted the cavalcade part of the way.

Traveling one stage behind the main convoy was Khusraw, the former rebel prince. At Nur and Harkha’s urging – and after listening to advice from the holy man Jadrup – the emperor had reconciled with his eldest son. Shah Jahan was watching his older half-brother closely for any sign that he was interested in succeeding to the throne.

A popular pilgrimage site along the route was Mathura, littered with temples of the playful god Krishna and his consort Radha. The people of Mathura anxiously waited for the Mughal party. For months, a tiger had been attacking villagers and visitors, then disappearing into the forest. Men and women in Mathura knew that an emperor could solve the problem.

According to one excited observer, the procession had nearly “fifteen hundred thousand’ (one and a half million) people, and ten thousand elephants and a great many armaments soon arrived.

Attendants began erecting hundreds of stunning tents, with the harem quarters marked with beautiful carved red screens. A group of local huntsmen appeared, paid their respects to the emperor, and begged him to do something about the killer tiger.

The emperor declined. He had taken a vow that he would give up hunting when he turned fifty. He’d promised Allah that he would injure no living being with his own hands. Now, two months past his fiftieth birthday, he had recently renewed his vow, as an offering to the gods on behalf of his favourite grandson, four-year-old Shuja, who suffered from epilepsy. It was said in those days that if you gave up a favourite thing as an offering to the gods, a seriously sick person would be cured. Shooting a tiger was now out of the question for Jahangir.

But the tiger-slayer empress was there. Just two years earlier, she’d amazed her husband and his courtiers by slaying four tigers with only six shots.

On October 23, 1619, the beautiful and accomplished Nur Jahan mounted an elephant and settled into the elaborate seat on its back. She wore a regal turban, much like the ones favoured by the emperor and noblemen, but highly unusual for a woman, and a knee-length tunic with a sash around the waist over tight trousers. Holding a tall musket, she looked stunning, with delicate earrings and a necklace of rubies, diamonds, and pearls. Her shoes were open at the back, exposing the henna designs on her feet.

The elephant handler led the empress along a sandy track toward the forest. Jahangir went on his own elephant, decorated with marigold garlands. A long line of courtiers followed. Some rode elephants or horses, while others walked alongside the attendants and local folks.

Local hunters on foot guided the party past fields of barley, peas, and cotton, lush from the recent rains. Along the way, they spotted herds of cattle, goats, and blackbucks with long corkscrew horns. When they reached the forest, the empress could barely see beyond the dense wall of creepers, bushes, and trees – lofty neem, thorny babul, and many others. The hunters showed the Empress and her retinue the spot where the tiger was likely to appear. They waited.

Soon Nur’s elephant, in the lead, began groaning and stepping nervously from side to side. Her seat lurched precariously. From his own elephant, Jahangir looked on, silent and focused. “An elephant is not at ease when it smells a tiger,” the emperor later wrote, and “to hit with a gun from a litter is a very difficult matter.”

The tiger emerged from the trees. Nur lifted her musket. Aiming between the animal’s eyes, she pulled the trigger. Despite the swaying of her elephant, one shot was enough. The tiger fell to the ground, killed instantly.

Jahangir was delighted. A woman shooting with such a large audience was highly unusual. A woman shooting with such expertise was unheard of.

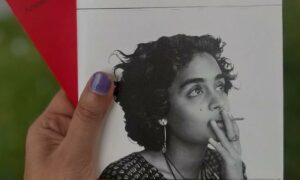

Excerpted with permission from Tiger Slayer: The Extraordinary Story of Nur Jahan, Empress of India, Ruby Lal, illustrated by Molly Crabapple, Penguin India.

This article first appeared on Scroll.in

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting