Can you prove you are an Indian citizen? I’m not sure I can.

So, I can only imagine what those without my privileges must endure in new India – plucked from homes or workplaces, their proof of identity dismissed, homes demolished, some forcibly transported to the Bangladesh border and pushed over, others erased from voter rolls and some stuffed into detention camps.

From Maharashtra to Assam, India’s offensive against “infiltrators” has begun, unannounced and arbitrary.

Many abandon fragile livelihoods to flee homewards to avoid detention and deportation. Some can do little as loved ones disappear or are carted off to detention. Others forsake daily wages for days or weeks to look for documents that might protect their vote and existence as Indians. Lives are upended, trauma is inflicted and families are torn apart.

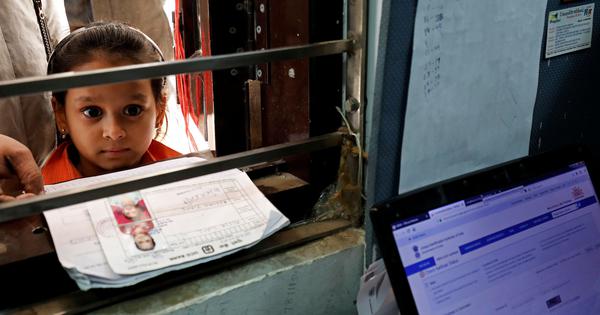

In this quest for identity, millions face the prospect of being reduced to second-class citizens – or stripped of citizenship altogether.

Why the government is subjecting some of its most vulnerable citizens to fear and displacement became clear on Independence Day, when the prime minister – without uttering the “M” word –announced the launch of a “high-power demography mission,” making what was unofficial, official.

“Today, I wish to warn the nation of a grave concern and challenge,” said Narendra Modi. “As part of a deliberate conspiracy, the demography of the country is being altered. Seeds of a new crisis are being sown. These infiltrators are snatching away the livelihoods of our youth. These infiltrators are targeting our sisters and daughters. This will not be tolerated.” And so on.

Modi offered no details on how the mission would work. But trace the arc from past events to unfolding developments, add in the disparate actions already underway against suspected “infiltrators” and a clearer, if unsettling, picture emerges.

A high-powered Demography Mission will work towards addressing the important challenge of demographic changes, especially in border areas. pic.twitter.com/aSdh07AZxL

— Narendra Modi (@narendramodi) August 15, 2025

Some of the current battles over citizenship have reached the courts, but what we hear is not encouraging because the very documents that people are frantically trying to collect may be of limited or no use, if recent court observations are anything to go by.

The Supreme Court said last week that voter IDs, Aadhar and PAN cards are not proof of citizenship but proof of identity to access services. Fair enough, but the Election Commission has now made clear its intention to reject these documents because it treats the verification of voter rolls as a test of citizenship.

The Bombay High Court said the same thing, although here the judges explained what might help prove that you are a citizen – “verification of the process through which these were obtained”.

I assume this means you must produce the documents that once got you the documents in question –a circular nightmare. To update or reconfirm them, you may have to provide proofs that themselves depend on those very documents: a chicken-and-egg trap, a classic bureaucratic paradox. This is the burden now placed on millions of Indians from Muslim and other disadvantaged communities, desperate to prove they are Indian.

To prove you are Indian in this febrile atmosphere – where the prime minister himself rails about “infiltrators” and his deputy about “termites” – is especially difficult because no one, certainly not the government, is clear what documents will be accepted to prove citizenship. Or, if it knows, it won’t say.

On August 5, a Lok Sabha MP asked the government what identity cards were “admissible proof” of citizenship. This was the government’s reply: “The Citizenship Act, 1955, as amended in 2004, provides that the Central Government may compulsorily register every citizen of India and issue a National Identity Card to him. The procedure for the same has been laid down in the Citizenship (Registration of Citizens and Issue of National Identity Card) Rules, 2003.”

On August 12, for the second time in a week, another Lok Sabha MP asked the government to specify the documents required to prove Indian citizenship. Again, the government wouldn’t list these documents, only saying, “The citizenship of India is governed under the provisions of the Citizenship Act, 1955, and rules made thereunder.”

In other words, the government wants its most vulnerable citizens to produce documents that prove citizenship but won’t accept its own identity documents and won’t say what specifically is proof of citizenship.

MHA did not specify the “categories of valid documents” required for people to prove citizenship in India, while responding to a Q in the Lok Sabha.

Data on the number of births registered in Bihar for the years 1998-1999 was “not available” I 🖋️ #SIRhttps://t.co/f4xo6s4KA0— Vijaita Singh (@vijaita) August 13, 2025

The national identity card that the government spoke about in the Lok Sabha does not exist. At this time, only a passport appears to be definitive proof of citizenship – although even a passport does not prove citizenship by birth – and getting one involves the same bureaucratic paradox that will collapse under the heightened scrutiny that Modi now promises.

Despite the personal privileges I referred to, let me narrate what happened to me last year when I moved into a new home and began the task of getting a new set of identity documents. I tried to update my Aadhaar with my new address, following the Unique Identification Authority of India website’s instructions, by submitting the sale deed of my flat or electricity bill.

It was, of course, too good to be true.

The website did not accept the sale deed, so I turned to the electricity bill. But first, it took four months to get the electricity connection transferred to my name and to receive the first bill. The electricity bill had my name second and my wife’s first. There was no place for my full name. The electricity transfer document did, but that was not on the list of accepted documents.

Off I went to the local Aadhaar enrolment office. Officials there said neither the sale deed nor the electricity bill were accepted any longer. But the website says they are, I argued. “Saar, website may say anything,” said the taciturn young man.

In the latest list of acceptable documents, there was only one that I could access: a recent bank statement showing my new address. And how did my bank get that address? I changed it myself in the bank’s mobile app after moving. The bank manager told me this counted as a “temporary” address, enough for the bank statement. The permanent address in their records would change after I updated my Aadhaar and gave it to them.

In other words: I needed Aadhaar to make my bank address permanent, but my self-declared bank address was enough to change my Aadhaar.

Since I now have my new Aadhaar, I should, in theory, be able to easily get a new passport. Passports are issued only to citizens, and applicants must provide proof of address and date of birth. The acceptable address proofs include Aadhaar and voter ID – both of which courts have said are not proof of citizenship.

The top court agreed with the EC’s decision not to accept Aadhaar and voter card as conclusive proof of citizenship and said they had to be supported by other documents.#ElectionCommission #SupremeCourt #BiharSIR https://t.co/hgG4AKZzsZ

— The Telegraph (@ttindia) August 13, 2025

To prove date of birth, you can use a PAN card – also declared by courts as no proof of citizenship. Yet, if you have all three – Aadhaar, voter ID and PAN – you can get a passport, the only real proof of citizenship.

I am neither Bengali-speaking, nor Kashmiri, nor poor, which means the police or Hindu vigilantes are not likely to invade my home or workplace or snatch me off the streets and demand proof of citizenship. A judge is not likely to scrutinise my papers and disrupt the circular illogic of my Indian citizenship. Well, at least for now.

If Modi’s “high power demography mission” gets going, expect everyone to scramble for documents and line up to bear the mass disruption that his government loves. Remember the queues of demonetisation and the long journeys of Covid. For those already running the formidable gamut of proving citizenship, the legal justification is rooted in the days of Empire: if the state suspects you are not a citizen, the law places the burden on you to prove otherwise.

Its legal basis lies in a colonial-era statute: section 9 of the Foreigners Act of 1946.

Around 6.5 million in Bihar were struck off the voter list revision, the exercise mutating into a covert citizenship test. In Assam, citizenship trials have pushed thousands into manufactured statelessness. Those excluded from the National Register of Citizenship in Assam are often undocumented Indian residents rather than being traditionally stateless, with citizenship of no country.

Assam, as the home minister made clear in 2019, was never the endgame – it was a rehearsal. “NRC aane wala hai [The NRC will come],” Amit Shah warned, referring to a national deployment.

The Supreme Court agrees with the Election Commission that it must only enroll citizens in its hasty review of voter rolls in Bihar – except it is unclear when the commission became an arbiter of citizenship.

There was some relief to the harried people of Bihar when the court on August 14 ordered the commission to publish the names of all 6.5 million excluded Biharis and explain why they were removed. But that order must be applied to every upcoming voter verification that the Election Commission has planned in the coming months in West Bengal, Assam and elsewhere. Otherwise arbitrary citizenship tests and mass disenfranchisement by electoral subterfuge will continue.

In any case, here is the Election Commission’s list of 11 approved documents for any new voter to be registered (and by default prove citizenship) in Bihar: domicile certificate, passport, birth certificate, caste certificate, Class 10 marksheet, forest right certificate, land/house allotment certificate, family register, national register of citizens (wherever it exists), identity card or pension payment order issued to regular employee or pensioner, and identity card or certificate or document issued by government, local authorities, bank, post office, public-sector companies or the Life Insurance Corporation before July 1, 1987.

Forget, for a moment, the hardship and agony this exercise caused. Let’s scrutinise these documents.

As I said, I have a passport and a bank statement with an address. But no more than 6.5% of Indians have a passport, according to the latest data the government submitted to Parliament in August 2024. In any case, passports could easily be taken off the list of citizenship proofs because of the uncertain nature of their supporting documentation.

The only reliable proof of citizenship by birth is a birth certificate, a document fraught with problems. Just over 62% of Indian children under five possess a birth certificate, according to the latest available data (National Family Health Survey-4, 2015-’16). Any move to impose the birth certificate as the gold standard of citizenship proof will cause nationwide chaos.

As Scroll has reported, using the same NFHS-4 data, 82.3% of children in the richest quintile had birth certificates, only 40.7% in the poorest quintile did. In rural areas, only 56% had, even in urban areas only 77% did. That leaves millions without birth certificates.

I have never laid eyes on my birth certificate, though my mother, Shailaja Halarnkar, swears “it’s there somewhere”. Since I had no name then, the document formally introduces me to the Republic as “Baby Shailaja”. Beyond that, the only unimpeachable evidence of my Indianness is my Class 10 marksheet – a fragile thread tethering me to the nation.

If – or when – the government decides to start afresh on citizenship questions, rolls out the national identity cards it mentioned last week in the Lok Sabha, and launches a nationwide National Register of Citizens, hundreds of millions will be forced to unearth birth certificates and who knows what other papers reaching back how many generations to prove they belong to their own country.

A version of this column was first published in Article 14, of which Samar Halarnkar is the founding editor.

This article first appeared on Scroll.in

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting