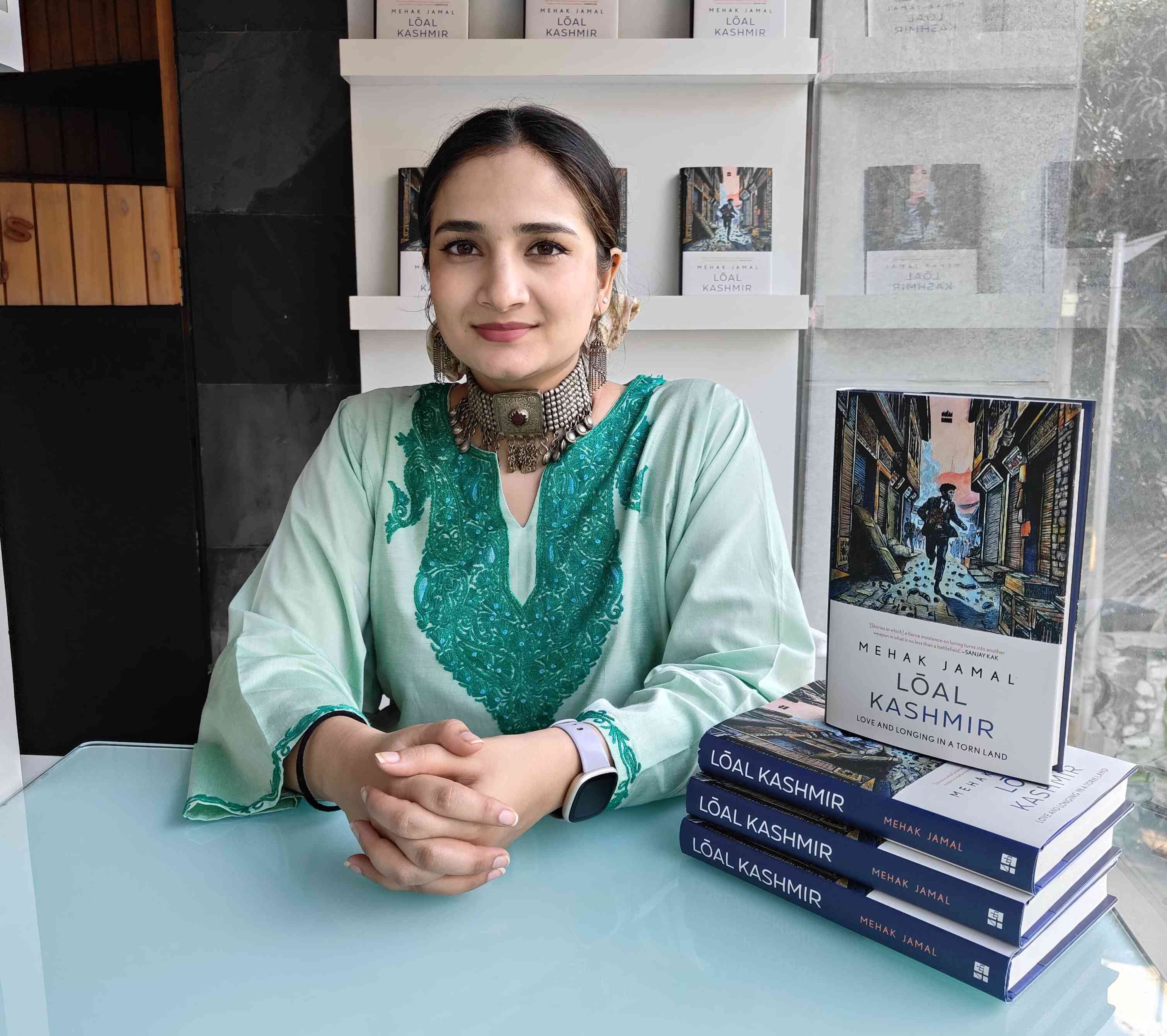

Lōal Kashmir: Love and Longing in a Torn Land by Mehak Jamal is unlike any book I’ve read about Kashmir. It does not directly document war, resistance, or politics, but instead, it lingers in the quiet, often unspoken world of love. Love as longing, as resistance, as something fragile yet fiercely persistent. The book has rightly been talked about widely: for its emotional candour, its archival urgency, and its refusal to separate the political from the personal.

But beyond the praise, I found myself wanting to ask questions that were more intimate, more complicated, questions that, since the publication of the book, have become even more relevant to the times we live in.

This conversation with Mehak Jamal is an attempt to address this urgent need, the tension, the tenderness, and the unsayable spaces that Lōal Kashmir so beautifully brings to light. Excerpts:

As someone who grew up in Kashmir, I’ve often found it almost impossible to explain to friends outside the Valley what a “relationship” means here. Romantic connections in Kashmir rarely resemble the ones depicted in popular media: there’s often no physical contact, no overt expressions, sometimes not even regular meetings. It can be as simple and sacred as a phone call or a shared silence (I have to be poetic in my exposition, come on, it’s Lōal we are talking about). And yet, those relationships carry immense emotional weight. Lōal Kashmir is the first book I’ve read that attempts to archive that quiet, coded world of Kashmiri love, where longing often stands in for touch, and distance becomes intimacy. How intentional was this act of documenting that specific emotional culture? Did you feel, while writing, that you were translating an entirely different emotional vocabulary, one that only those from Kashmir truly understand?

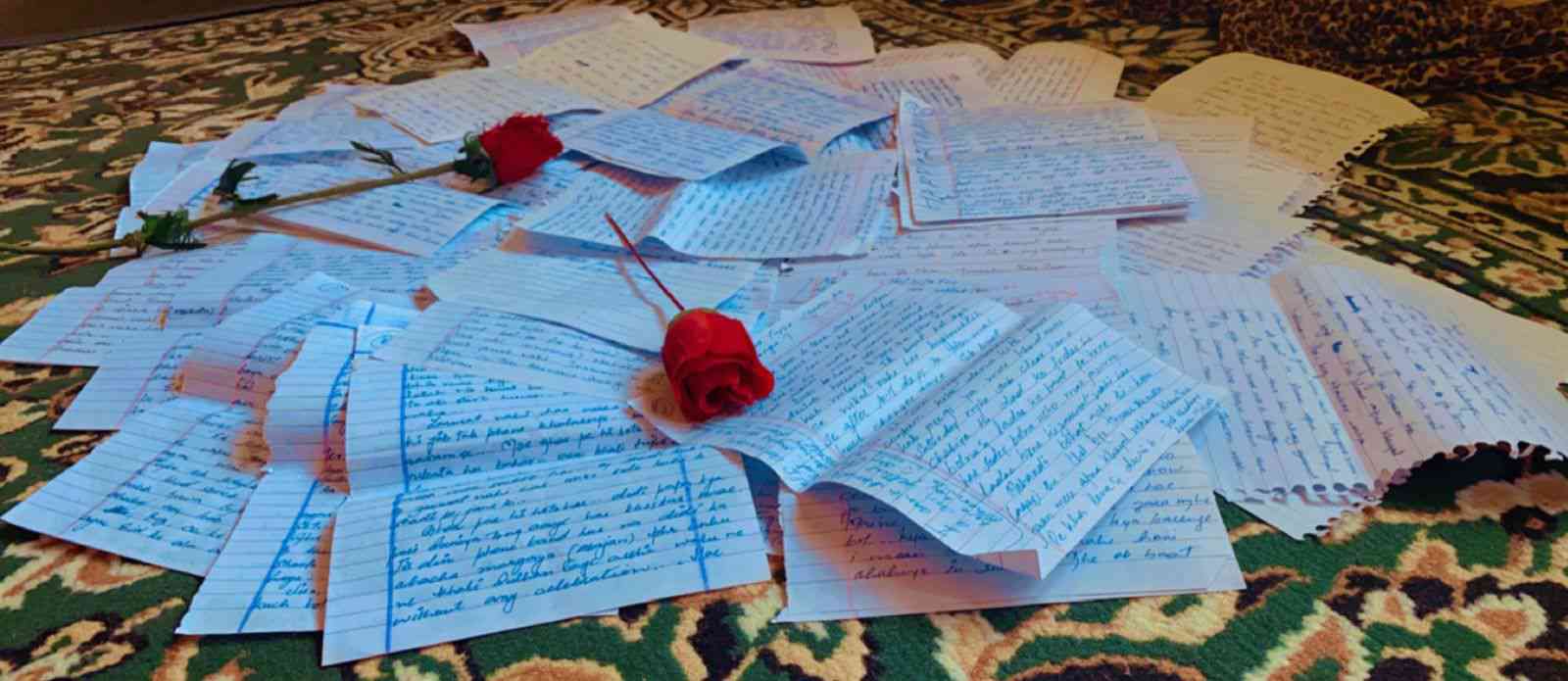

Having grown up in Kashmir and then moving away for studies and work, I was always surprised to find how love changed form outside of the valley. It was more obvious and direct, whereas back home, there was a whole song and dance around the fact that you liked someone. Of course, there are many facets of love in Kashmir which weren’t healthy; there was blatant stalking, eve-teasing and much more. If a guy had his sights on a girl and if she rejected his proposal, it was unthinkable to give up. If after a few years he was still around, silently pining away for her, that was a testament to his love. The girl would finally acknowledge this and say yes to him. This is just one scenario, and not a generalisation. But besides all of this, I have always thought that there is a quiet beauty to love and loving in Kashmir. Love can happen over a single glance at a tuition centre, a sideways giggle at a college debate, or over taesh-naer (hand washing jug and bowl) duty while washing a girl’s hands at a daawat. After the first meet-cute, a whole chain of events unfold – to make oneself known to the other, the desperation for a glance, the struggle to find a number, and then finally the dreaded words “mujhe true ho gaya hai”. Since Kashmir has been a conservative society, the concept of love before being betrothed was/is mostly seen as a no-no.

But curiously, this has never dissuaded anyone from expressing their love to another and dating in secret. Dating itself is a curious phenomenon in Kashmir. There are only a handful of public spaces for dates, and you must always look behind your shoulder to make sure a hamsaye (neighbour or relative) doesn’t see you gallivanting around the city. If you are seen, you know that inadvertently this news will reach home, and the end of that sentence is something you’d rather not find out. Adding to this intricate dance of being together but not being seen are the complications of the enduring conflict and the uncertainties that you find yourself in time and again due to it. This in itself leads to a sort of urgency when it comes to love and being with someone. I was very cognisant that there’s a very specific way that love unfolds in Kashmir, and I knew when I go to inquire about the same, this unique Lōal will make itself known in the stories. I was sure that many Kashmiris would recognise themselves in the pages of Lōal Kashmir, and I wasn’t disappointed.

One of the stories that truly struck me was Kashmiri in Gaza. I don’t think I ever imagined reading about a Kashmiri woman married to a Gazan, raising children between two occupied homelands. Amid the current genocide on Gaza, that narrative feels even more devastating, yet strangely connective. How did it feel to witness this rare but deeply symbolic union between two people shaped by two of the world’s most militarised, silenced places?

When I spoke to Laila (name changed) for the first time, I was shocked because I hadn’t thought that stories like hers were a reality, and surprised that she wanted to speak to me about her life. I have interviewed and collected most of the stories in the book around 2020–21. So I had been with them, lived and breathed with them for a while when the genocide begun in Palestine in 2023. As most Kashmiris do, I have always felt an affinity to Palestine due to the similarities in the conflicts in the two places. But this time around I actually knew someone who was there. I scrambled to find information about her and her family for days, and finally some time later I found out that they had been evacuated. I messaged her and she sent me a few words, in shock herself. It was only months later that I was able to formulate more words in my messages to her. Also I wanted to tell her about the book coming out, but it felt so trivial in the larger scheme of things. When I finally spoke to her, she had called me very early in the morning. I thought she was awake for sehri as Ramzan was going on. She just laughed wryly when I asked this, and said that they don’t sleep at night anymore. So deep was their trauma and PTSD of having been bombed in the middle of the night and fleeing.

Having lost their home and several family members, they remained vigilant at night even now, even though they were in a different country. She told me that they had become nocturnal. This was sometime in 2024 and I asked if I could add a note to the end of her chapter about what had happened with her post October 7, 2023, and she said yes. That is the note you see at the end of her chapter in Lōal Kashmir. Her story became all the more poignant and surreal to me after 2023, and I am honoured that it’s in my book. Also I cannot ignore the fact that she is one of the lucky ones that made it out of Palestine alive, as the genocide continues almost two years later.

Even though relationships are everywhere in Kashmir, everyone knows they exist in some form or another, there’s still an unspoken discomfort around openly acknowledging them. While religion and culture often discourage premarital relationships, even within the socially sanctioned space of marriage, love itself isn’t always something that’s comfortably expressed. Emotional vulnerability between couples, even that can feel taboo.

In your conversations while writing Lōal Kashmir, did you encounter this tension between what is permitted (like marriage) and what is still emotionally restrained (like love within it)? What did you learn about how Kashmiris navigate the expression or suppression of love, even in spaces that are technically “allowed”?

Talking out loud about your love is certainly uncommon in Kashmir. So when I was seeking these stories, I was very cognisant of this fact, therefore gave people the option to remain anonymous in their contributions. Which is why in most of the chapters, the names and details have been changed as the disclaimer at the beginning of the book says. What was interesting was that there wasn’t any rule of thumb when it came to people revealing their identity in the stories. A few people who were betrothed or married were comfortable with having their real identities, whereas many who were also married didn’t want their real names to be in there. Conversely most of the couples who were dating or whose love stories had not ended happily, wanted their names changed as well; then again, a few in these situations didn’t mind and kept their real identities. So if I go to analyse this, there is no particular pattern when it comes to talking about love aloud.

As you said, in spaces even where it is technically “allowed” and permissible, people aren’t comfortable with the world knowing about their love stories and are hesitant in showing affection to their partners. It is not commonly spoken about, nor do we grow up looking at married couples showing love and gratitude to each other. It’s all very hush hush and thus we internalise it ourselves that love should not be expressed in front of others. In my conversations, I found people wanting to break through this phenomenon – they wanted the world to know that they are regular individuals who live, love and go on with their lives. Even if they were reticent with their identities, they were unabashed with their sharing and telling of their personal stories. In so many of them, they expressed frustration about how clinical the society around them is when it comes to love and looks down upon a couple even hugging or holding hands in public, gestures that are quite normal. They wanted to break this illusion for themselves and others who read their stories. This just goes to show that when there isn’t enough importance given to the expression of love, it still finds its way in the world, through the defiance of people like them.

You write in the introduction that some stories were withdrawn out of fear. As a documentarian of love in conflict, how did you deal with those silences emotionally and structurally? Did you find yourself rethinking what it means to archive a people’s memory in a place where speech itself is fraught with uncertainties and danger?

This was a fear of mine right from the beginning and also why I gave people the option to remain anonymous. In a place like Kashmir, where you don’t know who is listening and who can twist your words into propaganda or worse, people are always a bit wary to talk about themselves and their experiences – especially since the conflict affects so many parts of their lives in big and small ways. But in spite of this, people opened up to me wholeheartedly and wanted to document their stories. I was also interviewing people in 2020 and 2021, with a few later on. That was a time when COVID was on a high and the impacts of the 2019 abrogation hadn’t set in properly. It was only later on, when I got closer to the release of the book, that I saw changes in a few of the people who had contributed to the book, because they were going through surveillance or censorship themselves, or knew of someone who had faced issues in similar situations. Some of these people weren’t willing to take the chance and withdrew their stories, whereas others figured that telling their stories in the book was the exact thing needed to circumvent what was happening around them. I went back into my interviews and chose more stories that I could add to the book, as well as interviewed specific, newer people whose narratives I felt were important to tell. To someone who reads the book as a whole, they might not notice the silences of the stories that were withdrawn, but I do feel the gaps sometimes, even though I respect the contributors’ decisions. Wanting to tell any kind of story in/from Kashmir is never an easy thing to execute, so I am immensely thankful to the ones who remained and chose to have their narratives be out in the world. Because at the end of the day, the news archives can be erased and history can slowly be altered, but collective public memory can become the indelible ink that remains.

This is a book about love but not the kind we often find in neat plot arcs or glossy novels. It’s lōal, love that contains within it longing, absence, memory, and defiance. In writing about such intimate emotions in a land so heavily burdened by silence and surveillance, were there books or writers you turned to? (I am surely reminded of Modern Love, the long-running New York Times column) Not just for craft, but maybe for courage or companionship?

If you were to recommend a small library of love for Kashmir or for conflicted geographies everywhere what would that look like? And more broadly, what spaces, literary or otherwise, helped you believe that everyday love, even in a place like Kashmir, deserves its own archive like Modern Love (I know I can’t stop bringing it up), which tends to unfold in coffee shops, subways or therapy rooms?

I think for me, two things became apparent at the beginning of gathering these stories in Kashmir. One was the documentation of life, like a memoir or a memory project, and secondly, looking at love. Both in the context of Kashmir were things that I didn’t find a lot of accounts of, and wanted to explore. Thus, Lōal Kashmir was born, not just to archive these stories, but to make them undeniable.

Farah Bashir’s girlhood memoir Rumours of Spring because it was deeply personal and emblematic of life in Kashmir growing up in the conflict. It was reminiscent of Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi talking about girlhood in Iran. Malik Sajad’s Munnu is another great memory document in the vein of Persepolis. Jhumpa Lahiri’s Interpreter of Maladies is a lovely collection of short stories about love and life. Modern Love is a great example, and it certainly was at the back of my mind when I started my project. India Love Project, documenting interfaith and intercaste love stories, is also something to check out in the same vein. As my primary craft is filmmaking, I often turn to films more than books. Wong Kar Wai’s Chungking Express and In the Mood for Love always define love for me. In terms of crafting stories, Krzysztof Kieślowski’s Dekalog and Three Colors, which explore and question different interconnected themes through an anthology, are always something I return to. They help me with progression in interconnected stories. I also watched Normal People right before I started my interviews and it really touched me with its complicated depiction of love. Looking at some similarities between Kashmir with Iran, I keep going back to Jafar Panahi’s films and I think many Kashmiris will relate to them.

The book opens with stories that are almost diary-like. Intimate, immediate, filled with the breathless hope of youth: first crushes, love letters, teenage codes whispered under curfew. But by the time we reach Agli Hartāl, we’re in the terrain of memory, illness, mourning, where love becomes a long endurance. Years ago, when I read Michael Ondaatje’s The English Patient, it followed somewhat the same arc, where fleeting wartime romance slowly stretches into an elegy for time itself.

Did you consciously design this arc to mirror such a progression – from ephemeral to eternal – or did these stories naturally fall into a rhythm that mirrored Kashmir’s own fractured temporality, where yesterday’s protest becomes today’s nostalgia? For instance, telling Nadiya and Shahid’s story, did you feel love itself became a kind of clock: a way to measure time in a place where history refuses closure?

The book’s progression has been thought out in a very particular manner. It invites you in subtly and then, through different time periods of the conflict in Kashmir, makes you a witness and holds you accountable at the same time. I was certain that “Love Letter” would be the first chapter, as it perfectly shows what it is to be a Kashmiri, the fear of being singled out, humiliation guised as camaraderie, and the kinds of contradictions that you face every day. In turn, the last chapter, “Agli Hartāl” is a reminder that when it comes to Kashmir, you never know where the next hartāl will come from – as Nadiya and Shahid see for themselves time and again. Also the progression of the book shows you that so much changes in Kashmir, yet the unrest is ever present – people have learnt to function around it, have become desensitised to it, yet it peaks out in their fears, anxiety and undiagnosed PTSD. And even though their lives and the landscape have evolved, the urgency of love, especially in the middle of a lockdown, hartāl or curfew, is unwavering. Nadiya and Shahid’s story is interesting as it traverses a decade or so, and they grow up from teenagers into individuals. Through multiple periods of unrest in their teens, their story finally reaches a breaking point during the abrogation in 2019.

While Nadiya is nonchalant in a “this is an everyday thing” kind of way, Shahid can see signs that this time it’s different – and it was. So when you make something so jarringly “regular”, any change in it can seem like the end of times. That’s what they and countless others in the book feel and go through, and it reflects in the way they choose to show and express their love. At times it’s soft and yearning, at others it’s frantic and urgent. Really, at the end of the day or rather the end of the hartāl, they are just searching for their one constant person – the one who tides them through difficult times, the one they look forward to seeing again – because in Kashmir, who knows where the Agli Hartāl will come from.

Bushra’s story in “Home Is Where the Heart Is” is filled with quiet longing for a home left behind across the Line of Control, for a life that politics disallowed her to return to. What makes her story even more heartbreaking now is its resonance with recent events: following the Pahalgam attack, several Pakistani women who had been living in Kashmir, some for over a decade, were forced to return to Pakistan by Indian authorities, while she herself wanted to return. In this context, how do you look back at Bushra’s story?

Similar to Laila’s story, I was suddenly rattled, because before these conversations with the contributors, I would never have known someone like Bushra or someone like Laila. So the events in the past few years and then recently, after the Pahalgam attack, really hit close to home. With Bushra, because I have been privy to her (and many women like her) struggle to go back home, I am always hoping that she is able to go. I even spoke to her when the deportations in India had begun post the Pahalgam attack, and she told me that she was “praying” that she, along with her children, would be deported back to Bagh in Pakistan-administered Kashmir, where she is from. There were so many heartbreaking stories of men and women from Pakistan who had willingly come to India through marriage and otherwise, living peacefully on a visa, but now were getting deported.

But in Bushra’s case, she actually wanted to go back. She and countless women like her had come to India-administered Kashmir when a Rehabilitation Policy for surrendered militants began in 2010. These men, who had been living in Pakistan and PaK for decades, had married women from there and had children as well. But as soon as they got back to India-administered Kashmir, in most cases, they were slapped with cases of entering India illegally (as many of them didn’t opt for the legal entry routes into India written in the policy). More so, the policy was quickly dissolved due to a change in governance and women like Bushra realised that she and her children were never getting citizenship or Indian passports. They were stuck. She has been living as a stateless person in Kashmir for over a decade. She hasn’t been deported back as the illegal entry case is still active against her. But even with the recent developments, as so many in mainland India got deported back to Pakistan, Bushra and women like her weren’t sent back – the only ones who really want to.

Throughout the book, even amidst shutdowns, surveillance, gun barrels, threats, beatings at the hands of the authority (whoever it may be), social pressure and shaming, people insist on love. They will just whisper ‘three words’ as a code for ‘I love you’ but they will profess it nevertheless. “…intangible dreams of people have a tangible effect on the world,’ Baldwin would write.

Did listening to and writing these stories make you or your subjects angrier about what has been denied to their generation or did they offer you unexpected hope?

I think there will always be a bit of both. When it comes to telling our stories, it is cathartic to be able to say them out loud and document them, as in many cases, historically, it has not been possible. It also provides hope because you feel that whatever you’ve been through is not for nothing. These stories can act as a memory capsule for future generations to know how people lived and loved in Kashmir. There are so many parts of our lives in Kashmir that we overlook in the context of the conflict. But I feel that the lived public memory of the conflict is as important to document and talk about as the conflict itself, because it becomes a powerful tool over time. As Kashmiris, there is always anger for what has been denied to us, but along with that, there is also the resilience and understanding to talk truth to power, so that no one can deny what has happened in Kashmir.

This article first appeared on Scroll.in

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting