Amidst the small houses made of mud and clay tiles, an under-construction cement building stood out in Salam Nawatoli village in Jharkhand’s Gumla district.

Most villagers said that the building was going to serve as a marriage hall under a government scheme. The gram pradhan of the village was not at home, but his son too echoed this belief.

“Everyone says the building that’s coming up is going to be a marriage hall,” said Saroj Devi, an anganwadi worker from the Asur community.

No one in the village seemed to know that the upcoming building was a multipurpose centre, sanctioned under the PM-JANMAN scheme.

Launched by Prime Minister Narendra Modi on November 15, 2023, the 148th birth anniversary of the Adivasi freedom fighter Birsa Munda, the scheme aims to benefit one of the most underprivileged categories of communities in the country: Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups, or PVTGs. The Asurs are among the best known PVTGs in Jharkhand.

“My government can’t stand by silently and watch you live in dire circumstances,” Modi said in a speech delivered from Jharkhand’s Khunti district, where Birsa was born. “The PM-JANMAN scheme will save 75 PVTGs from extinction.”

The budget for the scheme, announced in 2023, proposed an outlay of Rs 24,104 crore for the groups over three years.

It was sweeping in its scope: this money was to be spent on 11 “critical interventions” that would “saturate” the communities with facilities such as safe housing, clean drinking water, education, health, telecom connectivity and livelihood opportunities. It was to span 18 states, and nine ministries were to coordinate for the scheme, including the ministry of power, ministry of rural development, and the ministry of health and family welfare.

The scheme also involves the setting up of multipurpose centres, or MPCs, which aim to provide “multiple services to small PVTG habitations”, encompassing nutrition, health, culture, vocational education and financial inclusion.

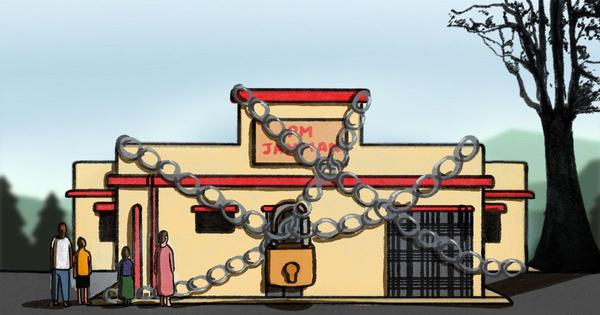

But, on the ground in Jharkhand, a state with around 4 lakh people who belong to these groups, the scheme is yet to make an impact. The multipurpose centres, the most visible manifestation of the scheme, have been slow to come up. And even where they have, they remain underutilised, with local authorities failing to create awareness about the purpose they are meant to serve.

The result of the information vacuum is that many members of PVTG communities have come to believe that the government is building marriage halls for them.

In the village of Salgi Pirhapathal, too, many assumed the new MPC building was a marriage hall. The village sits isolated atop a hill, and the building’s construction was completed in August this year.

“Some of us heard that this is going to be a community marriage hall, others were told that it’s going to be a hospital,” said one resident, Videsh Asur. “The building has not yet been inaugurated and we are still not sure about its purpose.”

In late October, I travelled to four remote villages in Gumla district and spoke to those who lived in areas where, according to government officials and ministry documents, the scheme was being implemented. I sought to understand how the scheme had fared on the ground and what changes it had brought to the lives of PVTG communities in Jharkhand.

What I found was a stark contrast to government claims about the success of the scheme. Many had not heard of the scheme. Those who had, and were aware of work in their village under it, said that the work was ineffective. In most crucial respects, including health and education, their lives remained unchanged.

“It seems people are reading that we are happy with the development work done for us by the government,” said Videsh. “But we ourselves don’t know what development work has been carried out for us.”

Scroll emailed the ministry for tribal affairs, and officials in Gumla responsible for overseeing the scheme, seeking responses to criticisms about its implementation and the lack of awareness about it. This story will be updated if they respond.

This story is part of Common Ground, our in-depth and investigative reporting project. Sign up here to get the stories in your inbox soon after they are published.

The government defines Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups as tribal communities that have a “pre-agricultural level of technology, low level of literacy, economic backwardness and a declining or stagnant population”.

In 1975, it identified 52 such highly marginalised groups, then termed “Primitive Tribal Groups”. In 1993, it added 23 more communities to this list, making a total of 75 such groups across the country. In 2006, the sub-category’s official name was changed to Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups, in light of the fact that the term “primitive” was considered pejorative and outdated.

In April this year, the government provided some specific information in the Lok Sabha about how it planned to help these communities through the JANMAN scheme. In response to questions, the minister of state for tribal affairs Durgadas Uikey stated that in three years, the government aimed to construct almost 5 lakh pucca houses, connect 8,000 km of roads and provide water supply to over 18,000 villages.

Uikey also stated that the government aimed to set up 1,000 MPCs under the scheme.

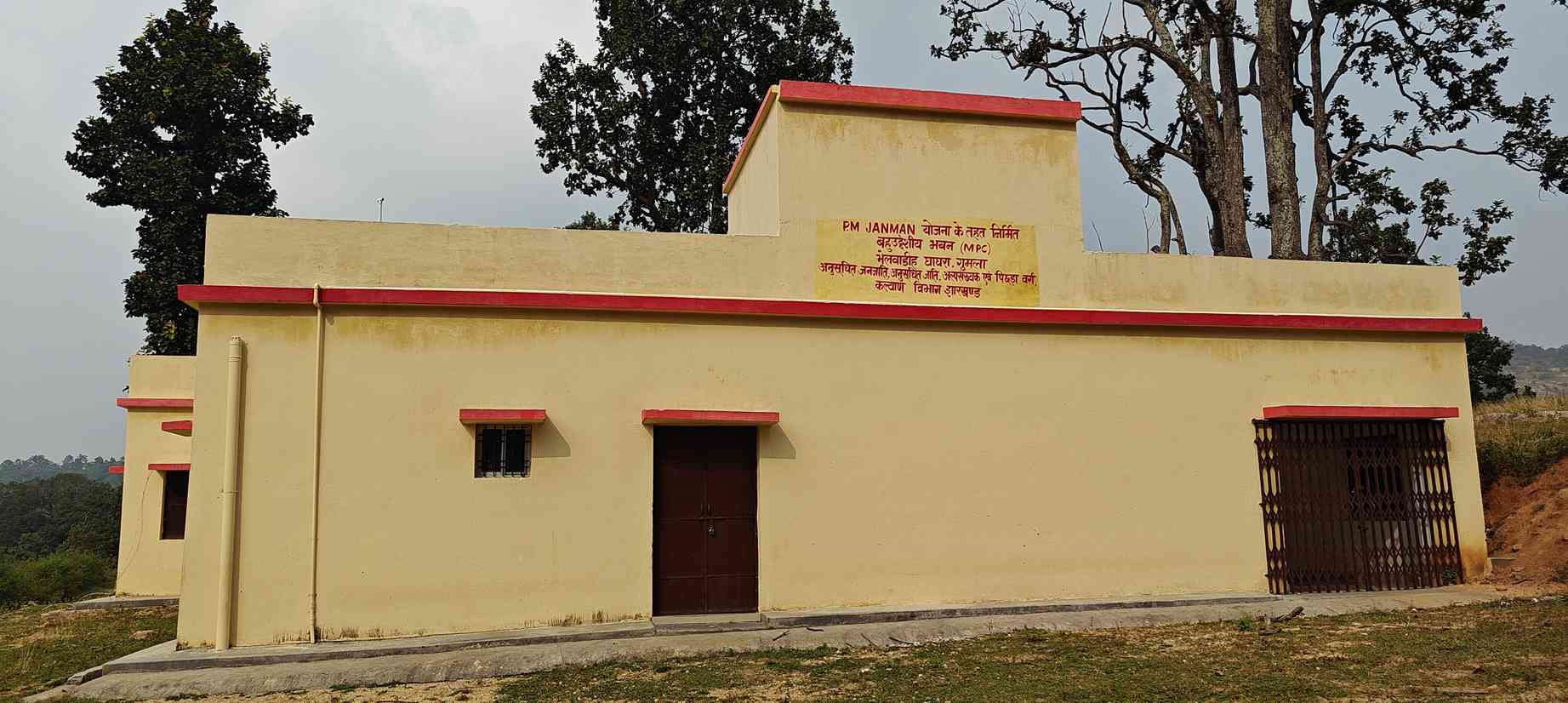

He added that since 2023, a total of 113 MPCs had been sanctioned in Jharkhand, and that Rs 2.12 crore had been released for their construction.

In Jharkhand, government officials in Ranchi and Gumla told me that around ten centres had been constructed in the districts of Gumla and Palamu. Two MPCs, I learnt, had started functioning in the villages of Bhelwadih and Range Tusrukona.

Accordingly, I visited these two villages, and two others – Salam Nawatoli and Salgi Pirhapathal – that were included in a list of sanctioned MPCs released by the ministry of tribal affairs in March 2024.

The village of Bhelwadih falls under the Ghaghra block of Gumla district. It sits atop a hill and has a total of three tolas, or hamlets – Purnadih, Injani and Banjertaar, all between two and three kilometers from each other.

When I visited the village at the end of October, the stony and uneven dirt road up the hill doubled the time it should have taken to drive up it. Passersby directed us to Banjertaar tola, which is the settlement usually referred to as Bhelwadih village. On reaching, I saw mud houses spread out by the side of the dirt road. Close to the houses, there were a few water tanks with signboards of the PM JANMAN scheme, but there was no sign of an MPC.

Locals explained that the only MPC in the area had been built in Purnadih, which had a larger Yadav population. They noted that most PVTG families lacked vehicles, and that visiting a tola even two or three kilometres away usually involved a time-consuming and inconvenient walk on dirt roads through fields and rivers.

“We wanted the MPC to be built in a midway between two hamlets so that people from both hamlets would be able to access it,” said Rajendra Asur, a resident of Banjertaar. “We fought a lot for this with people in the other hamlet, we also sent requests to the collectorate, but in the end, our prayers were set aside.”

I then made my way to Purnadih to speak to residents about the MPC there.

The hamlet stretches along a long road – houses, mostly made of mud, are far from each other, separated by fields. When we entered the village from the main dirt road, we were told that the MPC was at the other end of the village. A ten-minute drive led us to the Asur settlement, from where the MPC was a further five minutes away on foot.

“Quick, call your aunt, some people have come to see the panchayat bhavan,” said a woman to her child when we asked for directions to the centre. It appeared that the residents were not properly informed about the purpose of the MPC.

This is despite the fact that the scheme’s implementation guidelines, laid out by the ministry of tribal affairs, state that “during finalization of the location, a stakeholder consultation may be conducted at Gram Sabha/Panchayat level for type of land, location of the MPC, design, and construction oversight so as to build community ownership”.

As we reached the MPC, we saw a farmer working in the fields nearby. When I asked why the MPC was built so far away from the village the farmer, Bajrang Yadav, offered a justification. “Did you see the old school upon entering the village? It is in a ramshackle state today,” he said. “People weren’t able to safeguard it and now it’s broken and half destroyed. This is why we thought of building the MPC at a distance from the village.” One of the windows of the MPC was broken, as if a stone had been thrown inside.

Jeetni Kumari, an anganwadi sahayika and a resident of the village, arrived with the keys to the locked MPC. “This centre was opened sometime in June-July,” she said. “We run the anganwadi from one of the rooms.”

She noted that auxiliary nurse midwives, or ANMs, who provide basic healthcare services, also used the centre. “And the mahila mandal hosts meetings here,” she said. “That’s mostly all the work that happens here.”

The MPC had no water supply or electricity. “A borewell had been dug, but the water supply is not yet fixed,” said Jeetni. “We have to carry everything till here.”

She said that between 25 and 30 children came to the anganwadi centre regularly, but that the distance from the village and the other tolas made it inaccessible to many others. “It really is very far, we don’t even get mobile network here,” she said.

As we walked through the MPC, I observed aloud that there was not enough light falling indoors to light up the room. “We don’t really need the light in the daytime,” Jeetni said. “We make the children sit outside in the front yard of the building when it’s not raining.”

Except for a gas stove and some food provisions in one room used as the anganwadi, the rooms were sparse, with no furniture. “We just sit on the floor,” said Jeetni. “If required, we get chairs from houses nearby.”

The MPC also had a peculiar design for a modern building, with an open-to-sky courtyard in the centre. “There are drains for the water to pass through, so it doesn’t flood when it rains,” Jeetni said. “But the tiles in the corridor get dirty and slippery so they have to be cleaned.” She added that she had not been informed of other plans for future work at the MPC.

Two years after the launch of the JANMAN scheme, residents of these villages explained that there were numerous problems that they had been trying to resolve with the district administration for years, to no avail.

Banjertaar, for instance, had been struggling without an anganwadi.

An old anganwadi centre lay decrepit in the middle of the hamlet. “ASHA workers used to come regularly, but the centre would flood in the monsoons, damaging the building, so work stopped there some four-five years ago,” said Punam Asur, a young mother. “A new anganwadi is being run in Purnadih, but it’s more than two kilometres away from this hamlet, on the other side of the river. It is too far for our children.”

Thus, most parents do not send their children to any anganwadis. Since the hamlet also has no primary school, most sent their children to schools in the neighbouring village of Khukhradih or Ghaghra town.

PVTG residents explained that they also struggled to access their entitlements under schemes meant for them. This is despite the fact that a key objective of the PM JANMAN scheme is to, “streamline and simplify access to various government services by providing a centralized single window service centre with a comprehensive resource directory”.

For instance, PVTG communities are entitled to benefits under special schemes, such as the Dakia yojana, started by the state government in April 2017, which aims to deliver 35 kg of free rice to their doorsteps. “The contractors refuse to come up to the village, we have to go down to Ruki to collect our rations,” said Punam, referring to a village around 10 km downhill.

PVTG households are also entitled to avail of at least one social security pension – such as a widow, old age or disability pension if a member is eligible, and if not, to a pension under the Aadim Jan Jati scheme. However, Rajendra said that only a few received these pensions – he and others had been trying without success to obtain them for their household.

Some residents explained that they also struggled with procuring basic documents, such as Aadhaar and ration cards. The main reason for this was that to have their documents made, they would have to travel all the way to the district capital of Gumla, around 50 km away.

Residents of Salgi, meanwhile, have been struggling to procure water and electricity for the village. “There is no electricity or proper water supply here,” said Dinesh, a resident. “We have submitted multiple requests to the collector’s office in Gumla, to no avail.”

In early 2024, two water tanks were constructed in the village, but the borewells that were to supply water to them were never dug. A common tap connected to an existing well was also installed, but villagers said the water was not potable. “We have to go to the river to fetch drinking water daily,” said Dinesh. “It takes around half an hour to go down and climb back up.”

Videsh said that a few solar energy panels had been put up in the village a few months ago, and that villagers were hopeful that they would soon get electricity. “Who knows what will happen in the MPC, but we hope to at least get electricity and regular drinking water,” he said.

Here, too, education infrastructure was meagre – just one ramshackle primary school building. “There is only one teacher to manage the entire school, which has around 100 children,” said Videsh. “She comes from another village, so she is often in a rush. She cooks and feeds the children and then goes home.”

When children finish Class 5, they have to walk to the high school in the village of Adar, 5 km downhill, which takes them one and a half hours. “The high school is so far away that our children don’t maintain an interest in their studies,” Videsh said.

Healthcare facilities, too, are minimal. The nearest health centre, which is ill-equipped for major illnesses, is at least 10 km away. “For deliveries, pregnant women have to be carried down the dirt road by four men,” said a young woman nursing a child. “It is very dangerous, anyone could slip and fall down.”

With few livelihood opportunities nearby, most men in the village migrate to other states to work as labourers. “As opposed to larger Adivasi communities, the Asurs own very little land,” said Lalita Lakra, a social worker from Gumla. “And so agriculture is also not a standby livelihood option.”

Salam Nawatoli, where residents had assumed an upcoming MPC was a marriage hall, also grappled with healthcare problems.

“There were two children in the village who acquired disabilities in their legs while growing up,” Saroj Devi said. “They never got a diagnosis or the care they deserved.” On visiting the children, who are now in their early teens, the family informed us that they did not attend school, and did not receive disability pensions.

Devi herself had a swollen cheek when we met her. “My tooth hurts, I have to go to Gumla to get it extracted,” she said. “If this centre coming up provides us health services, we wouldn’t have to travel so far,” she said.

Elsewhere, villagers were more aware of the scheme, but little had changed in their lives.

Range Tusrukona in Ghaghra block is a village largely inhabited by the Birjia community. The construction of an MPC was finished last year, and it started functioning in August. Villagers noted that the centre was used for meetings, auxiliary nurse midwife consultations and camps for government services. “The ANMs come a few times in a month, and we also hold gram sabha meetings there at times,” said Archana Birjia, a resident of the village.

The keys to the MPC are kept with a member of the mahila mandal, who was not at home when I visited. The brand new building, painted a light beige, stood in stark contrast to other decrepit buildings around it.

Birjia noted that over the year, the MPC had also been used for a few camps for registering residents for Aadhaar cards and ration cards.

And yet, many residents said they did not have their documents in place. “There are a few children in the village who don’t have Aadhaar cards, and there are issues with their parents’ Aadhaar cards as well,” said Bindu Kujur, an anganwadi worker from the village.

She explained that this had serious consequences given the central government’s digitalisation of anganwadi services in 2022 – after this, children who attended anganwadis, or their parents, had to link their Aadhaar cards with the POSHAN app. “I’m not able to provide my services to them,” Kujur said.

Residents also face other problems with procuring documents as a result of niggling bureaucratic hurdles. For instance, villagers have not been able to procure Scheduled Tribe certificates because, though they belong to the Birjia community, in their land documents, they bear the surname “Agariya”, which is considered a different community – they explained that officials reject their applications, claiming that this is an inconsistency.

“Until school, people manage without ST certificates, but I know children who wanted to study further ahead and they have struggled to get admissions in college,” said Archana.

While villagers were glad that the MPC had been built, they felt other crucial work had been overlooked – such as repairs for the anganwadi centre. Kujur opened the door of one of the rooms to show how it was hanging on to the frame by just the bottom hinge. “This door could fall down any second,” she said. “I’ve been trying to get it repaired for months. I’m afraid that it will collapse on a child someday.”

The anganwadi centre was sparsely furnished, and while it had an electricity connection, it had no bulbs. “We received a budget of Rs 6,000 for repairs earlier in the year,” Kujur said. “The contractor fixed things but forgot to bring the bulbs, so things have remained this way. We manage with the sunlight coming in through the windows.”

Healthcare problems also persisted. As we spoke, a young child with a stye in his eye wandered around. “If he doesn’t get better, we will have to take him to the ANM the next time she comes,” Kujur said.

Archana recounted that in August, a six-month-old baby in her neighbourhood named Rajesh Birjia died after suffering from an undiagnosed ailment for a week. “He had broken out in boils that did not dissipate,” she said. “His parents first took him to Bishunpur for treatment, from there they were referred to Gumla. But he died by the time they reached. We still don’t know what exactly happened to him.”

Villagers noted that they had also not seen any improvement with regards to livelihoods and employment.

Though a year had passed since the MPC began to function, no camps or workshops on skill training had been held in it. This is despite the fact that one of the three key objectives of the MPCs, according to the government’s guidelines, is to facilitate the marketing and sale of forest produce, serve as skill development centres and improve financial inclusion. While there was some land in the village for agriculture, in the absence of progress on this front, several men travelled outside the state for work and women travelled to Gumla to obtain skill training.

Next to the village’s MPC stood an old and abandoned building overgrown with weeds. At the entrance was painted the words, “Komal Facility Centre”. Archana said that it was an old building that had been set up by the government for irrigation work, but had been abandoned years ago.

“Why construct a new building right next to an unused one?” the social worker Lalita Lakra said. “Couldn’t the government use the money to refurbish the old building and invest the leftover money on other requirements in the village?”

Archana agreed that there was other work that the village needed, for which government funds could be used. “We are free to use the MPC when we want to,” she said. “But actually we don’t end up using it for much.”

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting