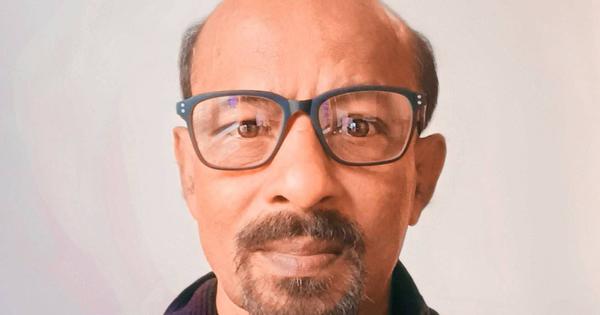

There are writers who come to literature as one might come to a shrine: with faith, caution, and awe. And there are others who arrive as a storm. Mogalli Ganesh (1963–2025) came as both. He entered Kannada letters with the humility of one who listens to the earth, and the ferocity of one who refuses to lie about it. Over four decades, he built an unrelenting body of work – stories, novels, poems, essays, criticism, an autobiography – that together form one of the richest and most original oeuvres in contemporary Indian writing.

To speak of Ganesh merely as a “Dalit writer” is to miss his true scale. He did not write from the margins or only about them. He wrote with a brilliance that asked questions to the margins and to the centres. His prose opened a door through which the silenced entered language as philosophers, not as victims, of pain. Ganesh carried forward the fierce inheritance from Devanooru Mahadeva and Siddalingaiah. In fact, he extended it from protest to inwardness, from identity to imagination. He realised the possibilities that his predecessors had announced.

His fiction – Buguri, Thottilu – are filled with silences that tremble like wounds under the skin of the sentence. He wrote as if each line had passed through fire. When his novel Thottilu (The Cradle) travelled into German, it breached the aesthetic quarantine that Indian literature often suffers in translation. His prose could be brutal and tender in the same breath. The pain in his world was never ornamental; it was an element, like air or rain.

In one of his poems, Everything Is Possible, he imagines himself as a meadow, a mountain, a river – forms of being that give shelter, knowledge, and thirst alike.

If I were a range of hills,

how many secrets would Nature itself have taught me,

feeding me the truth that knows

no high or low, no birth or death.”

When I translated this poem, along with nearly a hundred others – a project Ganesh himself followed with childlike enthusiasm – it felt to me as if he wrote not to describe the world, but to heal it through word. Each poem was a small act of restitution, a gesture of becoming water in a world of drought. He often told me how he hoped these translations would find a publisher who could carry their cadence across continents; we were still searching for that home.

Ganesh’s language had the sharpness of newly broken rock. It could suddenly turn to song. He was at once a realist and a mystic. His imagination was fed by what he called desi tattva – a native metaphysics born from the soil of Karnataka. In his critical work, Mogalli Vimarshe, he redefined what it meant to write from experience. For him, the writer’s task was to distil lived history into anubhaava – felt knowledge – and thereby to create a new order of truth.

If Devanooru Mahadeva gave Dalit literature its moral gravitas, and Siddalingaiah its lyrical insurgency, Ganesh gave it metaphysical depth. His work turned rebellion into reflection. He wrote of oppression, yes, but also of the trembling joy that persists beneath it. The small, invincible movement of the spirit that refuses to be annihilated was to him equally important. His characters are rarely triumphant, but they are always awake.

Ganesh’s poetry takes you by the hand and shows you the private and vast parts of life that aren’t spoken about. He lingers over a simple cup of tea in “The Cup,” but the scene feels endless: “This cup of tea is unfinished, / The everyday bowl of the Bodhi tree. / This infinite cup continues to fill.” Here, there is a quiet sense of reverence, as if love, care, and daily acts of kindness are sacred and always new. The focus then shifts upward and outward in “This Journey, So Far?,” assessing the moral effort and endurance of life: “Without causing harm or offense, / without taking from or trampling over others, / enduring indefinitely…” Ganesh gauges a person’s character by their ability to be patient, show subtle courage, and carefully tend to their own and the world’s wounds rather than by their success or wealth. The poem creates an environment where little acts of kindness, time, and effort add up to something nearly cosmic. The same voice eventually becomes more outraged and morally responsible in “Sleepless Nights”: “How did they become trapped / in the deformity of believing beautiful lies spun by criminals, / deaf to the cries of truth…” Here, Ganesh faces everyday injustice, cruelty, and corruption with an unwavering gaze. The reader is drawn into the heart of anger and sorrow, into a collective witness of pain and violation, as the lyrical intimacy of his other poems turns into a scathing vigilance.

Ganesh’s vision shifts between tenderness, introspection, and confrontation throughout his poems, all while maintaining a sense of presence. In one sentence, he writes about the domestic and the cosmic, the personal and the political. His poetry is both a hand held gently and a hand that shakes the world, urging it awake.

His autobiography, Naaneṃbudu Kinchittu (I is a Small Thing), is perhaps his most astonishing act of courage. In the recent discussion of the book, one senses how radically he redefined the form. The narrative begins with the self as hero and ends with the self as question. He strips his life to its bones, exposing the cruelties of caste, the betrayals of comradeship, and his own moments of failure. But there is no bitterness in the telling – only a deep, chastened clarity. Few Indian writers have faced themselves with such naked honesty.

He argued fiercely, but his anger was never sterile; it came from the moral core of a man who believed literature must answer to life. In the end, Ganesh’s work forms a kind of trilogy of consciousness: the fiction that dramatised the wound, the poetry that sanctified it, and the criticism that explained its anatomy. Few writers have been able to traverse all three domains with such conviction and grace. He has left behind not only an archive of writing but an attitude – a luminous unrest. His stories still smoulder in the grain of the language, his poems still echo with the rain of impossible tenderness.

He once wrote that if he could, he would become “sweet water to quench everyone’s thirst.”

Perhaps he did.

Poems by Mogalli Ganesh, translated by Kamlakar Bhat

Everything Is Possible

If I were a wide open meadow,

how many creatures would have found in me

a sanctuary of food and shelter!

If I were a field

of many-hued flowers, fruits, and vines,

how many butterflies would have kissed me,

and returned again with the changing seasons!

If I were a range of hills,

how many secrets would Nature itself have taught me,

feeding me the truth that knows

no high or low, no birth or death.

If I were the rocky spine of a mountain

and within it, a single tree –

how many living beings

would have built their nests in me!

What have people like me,

born human, really done?

What use is it to complain

how many have led us astray?

In innocent disguises,

how many barbaric dramas we stage –

all these light-devouring pits

are of our own making.

Streams, brooks, rivers, the sea –

each flows its separate way,

yet all long to become

the water of the rain.

If only I could –

I would become sweet water

to quench everyone’s thirst.

The Cup

I keep sipping little by little,

Yet the cup of tea is never empty.

It is the one she made

With milk and sugar from her own kitchen,

Serving it hot.

A sweet fragrance fills my life

With steamy joy

And tender romance.

She takes a sip,

I take a sip,

Our lips meet in a kiss.

It doesn’t rust,

Time never ends,

And there is no boredom.

Each has their own sip and bite,

Their own way and time,

Their own cup of tea.

It hasn’t slipped or gotten dented,

Hasn’t lost its color or taste.

She washes it, cares for it, and makes tea in it.

With careful reckoning, straining, and preserving,

Providing with the essence of life,

She smiles through the milk-feeder.

She is my lifeline,

I am hers,

And we keep savouring life’s goodness.

This cup of tea is unfinished,

The everyday bowl of the Bodhi tree.

This infinite cup continues to fill.

This Journey, So Far?

Without causing harm or offence,

without taking from or trampling over others,

enduring indefinitely,

without jeopardising anyone’s livelihood,

tending to one’s own wounds,

bearing all pain with a gentle smile,

is it servitude, a jest, or timidity

to have climbed the peaks burdened thus,

and with a nod of respect?

Isn’t one’s achievement mountainous?

Who birthed this timeless journey?

Who is the ancestor of this stream?

Who crafted the cradle and danced to time’s tune

in these graveyards?

Who has nourished the deprived with moonlight

and helped them persevere?

Where have all the air, water, and light

soaked in by one disappeared to?

Where have the atomised particles dispersed?

Has the sea’s thirst been quenched?

So many pathways explored, isn’t it enough?

Sleepless Nights

Where do they go with hands painted in ugly blood,

hearts brimming with disgust,

acting cruel yet feigning innocence,

exuding barbarism, igniting both day and night?

How did they become trapped

in the deformity of believing beautiful lies spun by criminals,

deaf to the cries of truth,

celebrating the exploits of killers?

Even if truth’s eye is veiled,

why doesn’t dark regret strike like lightning?

Why does murderous rain fall at dawn?

Why does the dark shadow of prey

besiege this day, this evening, every day?

What’s on the plate: food or filth?

Who has arrived?

What’s been consumed, what’s the game?

When saris and blouses are ripped in the streets,

can eyes widen in astonishment?

Can courts turn a blind eye?

How did this hunt begin?

What is guilt?

How does one claim an inheritance of immorality?

What audacity strips the nation bare

and sells mother’s sarees?

What shamelessness crowns looters as rulers?

Does no one feel revulsion

at this ravenous laughter

while devouring cannibalistic biryani?

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting