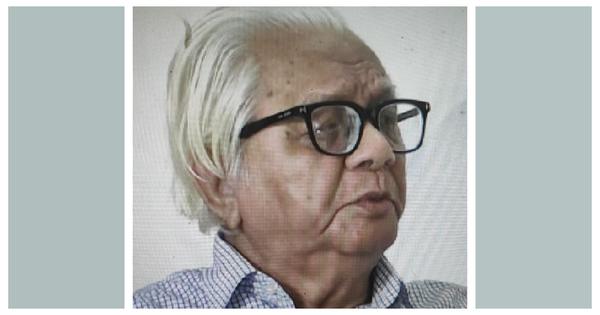

When students brought down Sheikh Hasina’s government in August 2024, Bangladesh witnessed its latest cycle of mass uprising followed by uncertain transformation. Badruddin Umar, who died on September 7 at the age of 93, had spent seven decades documenting precisely these patterns. He studied how genuine democratic movements repeatedly emerged in Bangladesh, only to see their revolutionary potential absorbed by the same elite structures they initially challenged.

Umar was Bangladesh’s most uncompromising Marxist intellectual, a historian whose analysis of political movements proved more prescient than the strategies of the politicians he studied. His death removes one of the few voices capable of connecting contemporary crises to their roots in the failures of postcolonial development.

The tragedy is that Bangladesh desperately needed the kind of systematic analysis Umar provided, whilst ensuring he remained largely unread and politically irrelevant.

Born in 1931, Umar witnessed the entire arc of Bengali political development. He lived through Partition in 1947, when British India split into India and Pakistan, with East Bengal becoming East Pakistan, separated from West Pakistan by a thousand miles of Indian territory.

He saw the various uprisings of 1969-’71 that led to Bangladesh’s independence.

In his final year, despite his age, he supported the 2024 student uprising that finally toppled Hasina’s government, recognising both its democratic potential and its limitations.

From the Archives:

Writer and political analyst #BadruddinUmar talks to The Daily Star about the student-led uprising and student politics.#Bangladesh https://t.co/rs8Ze6JYWW— The Daily Star (@dailystarnews) September 7, 2025

Umar’s significance lies not in his longevity or his witness to these transformations. It lies in his ability to analyse why each democratic breakthrough failed to produce lasting change. His method was historical materialism applied to specific conditions rather than abstract theorising.

He insisted that political movements could only be understood by examining the class interests that shaped them, the economic forces that constrained them and the organisational dynamics that determined their success or failure.

His analysis of the language movement demonstrates this approach. The 1952 protests that forced recognition of Bengali as an official language appeared to represent a democratic victory over authoritarian rule. Umar recognised genuine popular content in the movement.

Students, railway workers, government employees, and ordinary citizens united across religious lines in opposition to linguistic discrimination. The police firing on protesters on February 21 transformed cultural demands into political insurrection. But Umar also identified the movement’s crucial limitation: its focus on cultural recognition rather than economic transformation.

The Awami League, which emerged as the movement’s political beneficiary, successfully channelled democratic aspirations into a nationalist project that challenged Pakistani cultural domination whilst preserving capitalist social relations.

The party that mobilised the population against Urdu imposition would later suppress linguistic minorities and tribal peoples once it controlled state power.

This pattern of elite capture recurred throughout Bangladesh’s political development. The liberation war of 1971 promised independence from Pakistani oppression but established new forms of domination by local elites connected to global capital.

Each subsequent uprising brought down particular governments without transforming the systems that generated authoritarian governance.

Umar understood these cycles through analysing how power operates in postcolonial societies. Countries like Bangladesh achieved formal independence whilst remaining economically dependent on global markets and politically dominated by local elites who served as intermediaries for international capital.

Democratic movements could challenge rulers whilst leaving intact the structures that produced inequality and exploitation. His documentation of failed revolutionary strategies illuminated these dynamics.

The Communist Party’s disastrous ultra-left turn in the late 1940s, which attempted armed struggle without mass support, isolated revolutionaries from the populations they claimed to represent. Heroic peasant uprisings in rural areas remained confined to tribal communities, where they could be easily suppressed and distorted as communal violence.

Meanwhile, moderate political parties like the Awami League learnt to mobilise popular grievances whilst accommodating elite interests. They promised autonomy from central control whilst preserving local hierarchies. They celebrated cultural identity whilst avoiding questions about economic exploitation. They organised mass movements that channelled democratic energy towards projects ultimately serving ruling class consolidation.

Chief Adviser Prof Muhammad Yunus on Sunday expressed deep shock at the death of prominent writer, researcher and left-leaning intellectual Badruddin Umar.#ChiefAdviserGoB #news #DailySun pic.twitter.com/CVCN7zpYX3

— Daily Sun (@dailysunbd) September 7, 2025

Umar’s later writings revealed growing frustration with these patterns. The Marxist-Leninist groups he belonged to operated through “fronts and affiliates, all very small but at the same time often sounding quite ambitious”.

This capacity for ruthless self-criticism distinguished Umar from intellectuals who substituted revolutionary rhetoric for strategic thinking. His marginalisation reflected broader patterns in how peripheral societies neutralise critical voices.

The Bengali elite had no use for analysis that exposed the class foundations of their nationalist project. International academic circuits preferred theoretical abstractions to concrete studies of postcolonial politics. Revolutionary organisations valued ideological orthodoxy over strategic innovation. Umar fell between all these categories, producing work that was too critical for liberals, too empirical for theorists, too Marxist for nationalists.

Yet this isolation also preserved his analytical independence. Unlike intellectuals who oscillated between government patronage and opposition politics, Umar maintained a consistent distance from all forms of power. This position allowed him to identify democratic content in popular movements whilst avoiding illusions about their likely trajectory.

His support for the 2024 uprising combined recognition of its mass character with realistic expectations about elite responses. The question haunting Umar’s legacy concerns why intellectual clarity proved irrelevant to political transformation. His generation of leftist thinkers produced sophisticated analyses of capitalist development, imperialist penetration, and class struggle in postcolonial societies.

But they failed to build organisations capable of sustaining mass movements beyond moments of crisis. Whether this reflected theoretical inadequacies, organisational incompetence, or structural impossibilities remains contested.

What seems clear is that Umar’s analytical framework illuminates contemporary Bangladesh’s predicaments better than the political strategies of his contemporaries. His understanding of how elite nationalism absorbs and redirects popular democratic aspirations explains the cycles of mobilisation followed by disappointment that characterise Bangladeshi politics.

The conversion of genuine grievances into electoral opportunities, the systematic exclusion of working-class interests from political discourse, the subordination of democratic participation to elite competition: all these patterns that Umar identified in the 1950s continue shaping political possibilities today.

Rest in peace to the great Badruddin Umar—the towering chronicler of the Language Movement and leader of the Communist Party of Bangladesh pic.twitter.com/tsh9nnlvFh

— mahdi (@_mahdichowdhury) September 7, 2025

The challenge for those who inherit Bangladesh’s political future involves building on Umar’s insights whilst avoiding the isolation that characterised his later years. This requires neither abandoning critical perspective nor retreating into academic irrelevance, but developing forms of political practice capable of sustaining mass organising over time.

Contemporary Bangladesh faces the crises Umar analysed throughout his career. Deepening inequality persists despite economic growth, environmental degradation threatens millions, whilst development projects benefit connected elites, authoritarian governance continues across different political parties, and integration into global markets increases rather than reduces dependence on external forces.

The 2024 uprising created possibilities for addressing these challenges, but only if its participants understand the dynamics that frustrated previous movements. This requires grasping how elite capture operates, how democratic aspirations get channelled into safe directions, and how genuine popular energy becomes fuel for projects that ultimately serve ruling class interests.

Umar’s death removes a voice that understood how societies reproduce domination whilst promising liberation. His legacy poses a fundamental challenge: whether Bangladesh’s current democratic opening can avoid the patterns he documented so meticulously.

The revolution may still be possible, but only if its protagonists learn from the failures that Umar spent his life analysing. These were failures not of revolutionary vision but of the organisational capacity to sustain popular democracy beyond moments of crisis.

Whether anyone was listening to the intellectual, his country never heard may determine whether this latest uprising produces a genuine transformation or simply another rotation of elite power. That question, more than any monument or memorial, represents the most appropriate way to honour Badruddin Umar’s uncompromising commitment to revolutionary possibility in the face of repeated defeat.

Ankush Pal is a sociologist trained at the London School of Economics and Political Science who researches and writes on pubic space, South Asian culture and urbanisation.

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting