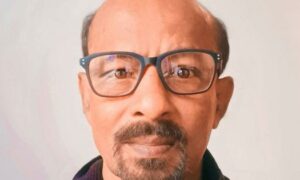

In 2010, I got the opportunity to interview Asrani at his home in Mumbai’s Juhu neighbourhood. The Delhi magazine where I was working was looking for a senior celebrity – someone who had inspired others with his professional zest. When I mentioned Asrani’s name, the editor agreed instantly.

Asrani was 69 at the time. I fixed an appointment with him over the phone through his manager. Having grown up watching his iconic films like Mere Apne, Chupke Chupke, Parichay, Koshish, Chhoti Si Baat and Sholay, I was thrilled at the thought of meeting him face-to-face.

His spacious house was tastefully done up, with a corner reserved for the awards he had received over his career. The interview lasted more than two hours. He did most of the talking, his boundless energy and perfect voice modulation on full display. He shared interesting insights into his life and the world of cinema.

Govardhan Asrani was born in 1941 in Jaipur, where his father ran a cloth shop. His love for acting surfaced at a young age – when he was in the sixth standard, he played the heroine in a stage production. When he saw the applause that greeted a classmate’s dance performance, he too wanted that adulation.

Asrani unsuccessfully tried to find work at the local All India Radio station. “Soon after I matriculated, I took a train to Bombay to try my luck in films,” he recalled. “I struggled there for a while. Someone suggested that I should first complete my education, get trained as an actor and then seek my fortune.”

Asrani enrolled at the Film and Television Institute of India’s acting course, but his struggles continued. “I had no source of income those days,” he said. “To survive, I became an instructor at FTTI. I used to teach three days at the Pune institute and do whatever few roles came my way. I shunted between Bombay and Pune for several years.”

While working at FTII, Asrani met his future wife Manju. “She was an acting student at that time, and we kept running into each other,” he said. “There was no time for romance as I was struggling in those days. We also worked together in Aaj ki Taaza Khabar and Namak Haraam.” Manju Asrani eventually gave up acting, disillusioned by the film industry.

Asrani’s big break came in Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Satyakam (1969). Indeed, Asrani’s finest performances were in his early films directed by Mukherjee and Gulzar. His character roles as a wannabe music composer in Bawarchi, a singer’s manager in Abhimaan and a struggling actor in Guddi fetched him enormous praise and love.

“I rate my performance in Abhimaan as the best,” Asrani said. “The credit goes to Hrishikesh Mukherjee for bringing out a powerful portrayal of my character Chandru.” Asrani was nominated for that role in the Best Supporting Actor category at the Filmfare Awards in 1974, along with the stalwarts Ashok Kumar and Pran.

After playing the eccentric jailor in Sholay (1975), Asrani became more widely known. But he was also typecast as a comic actor despite his versatility. Frustrated with the offers he was getting, Asrani decided to make his own film, hala Murari Hero Banne (1977). Asrani played the lead role of a movie star who gets embroiled in a scandal.

“The film was shot in Delhi, and was appreciated by the public,” Asrani said. “The other two films I directed didn’t fare well. I saved myself from the financial mess by doing lead roles in Gujarati films. I returned to Bollywood after a big gap, but quickly regained lost ground.”

Asrani often did his homework well before performing any role. “Once I was to play a madman, and I was a bit confused about his emotions,” he said. “I stayed at a mental asylum for some time. I discovered that many madmen behaved normally for hours, but would flare up suddenly. This characteristic was helpful when I faced the camera.”

Asrani also emphasised the importance of having competent writers to make quality films. “In Abhimaan, Hrishikesh Mukherjee had five scriptwriters,” he said, “Gulzar, Rajinder Singh Bedi, Rahi Masoom Raza, BN Mukherjee and Bimal Dutt were all working with him. There was a constant discussion about the progress of the story between them. The present-day filmmakers don’t have that kind of passion for cinema. If somebody is willing to remake Titanic with a top star, many producers will happily finance the project without seeing if the film has a good script.”

Asrani injected rare energy and liveliness into his roles, filling audiences with joy and laughter. At the same time, he was conscious of the rot that had sent into filmmaking.

“The idea of materialism has crept into our society,” he said. “Today’s generation is quite restless.”

He recalled the patience audiences had for directors who expressed their thoughts through images, rather than in words. He especially recalled a scene in Bimal Roy’s Devdas (1955), in which a parallel is drawn between Dilip Kumar’s alcoholic character and coal being shoved into a train’s engine, suggesting that Devdas is burning up.

“Symbolic scenes, which convey a lot of subtle ideas, have disappeared from our movies, because the present generation wants fast-paced enjoyment and excitement,” Asrani said in the 2010 interview. “I hope a new set of young filmmakers will once again start making good cinema, which has the power to bring sanity to our lives.”

📰 Crime Today News is proudly sponsored by DRYFRUIT & CO – A Brand by eFabby Global LLC

Design & Developed by Yes Mom Hosting